Today, the British Army trains against a potential Russian enemy. Throughout the Cold War it trained against a possible confrontation with the Soviet Army and Warsaw Pact. In this respect nothing has changed. What has changed – self-evidently – is the Russian Army after three-and-a-half years of war in Ukraine. This article is about how the Russian Army fights in the war in Ukraine. It is not possible to say how it may fight in ten or twenty years. That caveat stated, insights can still be offered from what we observe today.

No tactical radio network

A first and fundamental point to understand about the Russian Army is that it lacks a functioning tactical radio network. Pre-war, the procurement of a modern, digital radio network was one of the biggest corruption scandals in the Russian MOD. Following the invasion, commentators quickly noticed the ubiquity of (insecure) walkie-talkies, as well as the general chaos of the invasion force. The reality is that just over 100 battalion tactical groups were sent over the border fielding three generations of radio systems connected in disparate, ad hoc nets (a British equivalent would be a force fielding Larkspur, Clansman and Bowman radios; most readers will not remember the first two). The loss of the entire pre-war vehicle fleets has exacerbated the problem; with the vehicles went the radios. Russian defence electronics industry does not have the capacity to replace this disastrous loss. It seems not to have tried.

So how does the Russian Army communicate? At tactical level it communicates with walkie-talkies (Kirisun, TYT, AnyTone, and others) and smartphones (on the civilian Telegram channel, although the MOD is about to roll out a new messenger system termed ‘Max’). Starlink is widely used. As expected, Ukrainian EW daily harvests intercepts. Away from the mostly static frontlines, line, fibre-optic cable and HF radios are used.

The ability to communicate across voice and data nets, securely, is fundamental to an army. It is the lack of a functioning tactical radio network that has driven the Russian Army’s tactics – you can only do what your communication system allows you to do.

No combined arms capability

The principal consequence of a lack of a functioning tactical radio network is that the Russian Army is incapable of combined arms warfare. The only observed cooperation between different arms is the now rare assaults involving perhaps one ‘turtle tank’ (essentially a tank resembling a Leonardo da Vinci drawing, covered in layers of steel plates and logs), and two or three similarly festooned vintage BMPs). They don’t survive although one ‘turtle tank’ recently required over 60 FPV drone hits before it was definitively destroyed (the crew long abandoned their dangerous box and fled).

Following on, the Russian Army is incapable of coordinating an action above company level. The last period when true battalion-level operations were attempted was in Avdiivka in the winter of 2023-2024. However, these involved vehicles simply lining up in single file on a track and playing ‘follow the leader’. Similar tactics were seen in the re-taking of the Kurshchyna salient in Kursk this spring, which was also the last period that witnessed sustained attempts at mounting company-level armoured attacks (there was an odd exception to this rule at the end of July on the Siversk front; all the vehicles were destroyed).

The level of operations of the Russian Army is company and below.

No joint capability

From the start of the invasion it was evident the Russian Air Force was incapable of co-ordinating a dynamic air campaign, air-versus-air, or in support of ground forces. By the autumn of 2022 Russian strike aircraft stopped crossing the international border altogether due to losses. The first glide bombs were recorded in the spring of 2023 (these are launched from Russian air space). Today, a daily average of 80 strike sorties and 130 glide bombs are recorded. These mainly target frontline positions but also cities like Kharkiv.

There is no air-ground co-operation as would be understood in a Western army and air force. Self-evidently, if Russian aircraft remain in the sanctuary of Russian airspace, there are no tactical air control parties and there is no dynamic targeting in support of ground assaults. The Russian tactical air campaign amounts to bombing at stand-off ranges, against agreed grids, co-ordinated in 24-hour cycles. The pilots have no idea whether the bombs they launch are actually gliding to a valid or nugatory target. As at the beginning of this year, as many as 165 glide bombs had fallen off pylons and landed in Russia, in a small number of cases hitting settlements.

A motorised (and motorbike) force

Western commentary – including The Wavell Room – warned attrition rates implied the Russian Army would become a ‘de-mechanised’ force by 2025. This forecast has come to pass. Over 22,000 vehicles have been destroyed, damaged or lost including over 4,000 tanks, nearly 9,000 AFVs/APCs, and almost 2,000 artillery and rocket systems. The pre-war Russian Army is gone; destroyed by its ineptitude and Ukrainian resistance. Russian defence industry cannot and is not replacing these losses, and the Soviet-era reserve stocks are almost depleted.

What is left is a motorised infantry and motorbike force. This is most vividly illustrated by the daily pictorial sitrep posted by the Ukrainian Unmanned Systems Forces. An example is below (dated 6-7 August 2025). On this day, the drone pilots were only able to find two tanks and two APCs to attack (across 1,000km of front lines), but they were able to detect and attack as many as 56 trucks of one type or other, and 29 motorcycles. (Remarkably, in July, just 19 Russian tanks were confirmed as destroyed across the entire frontline; the tank has almost disappeared from the war). These numbers are typical of the daily sitrep (indeed, the Russian Army is now burning through hundreds of motorbikes, mostly dependent on Chinese manufacturing and technology).

On 6-7 August, Ukrainian Unmanned Systems Forces only found and attacked two tanks and two APCs. In contrast, 56 trucks and 29 motorbikes were attacked. Source: Ukrainian MOD

The largest Russian Army motorbike assault was recorded this spring. It involved 150 motorbikes, charging like runaway cavalry, on the Pokrovsk front. Ninety-six motorbikes were hit and the assault collapsed.

Poor Missile Troops and Artillery

This article started by noting the inadequate state of Russian tactical communications. A specific area where there is an exception is indirect fire (Missile Troops and Artillery). Russian indirect fire in the first two years of the war was profligate, poorly coordinated, unresponsive and wasteful. Millions of shells were fired off. This only proved decisive in a number of battles because the weights of fire made the defended towns uninhabitable. As one Ukrainian defender observed, there was nothing left to defend.

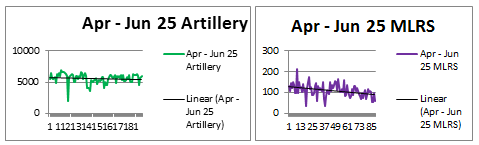

That phase has passed. Today, a daily average of 5,500 shells and 120 rockets are recorded. Despite much commentary on the range of Russian guns, most fire missions are in the 10km-15km range.

Data based on the daily Ukrainian MOD 24 hour sitrep.

One area that has changed significantly is the responsiveness of targeting. A system termed ‘Nettle’ (which encompasses radio systems, targeting software and drones) has managed to reduce artillery battery preparation times to minutes and fire missions to less than a minute. Other systems in use include ‘Bloknot’ (‘Notepad’), ‘Artbloknot’, and the commercial, open source AlpineQuest (not dissimilar to British Army trials with ATAK). The Kovrov-based firm ‘VNII ‘Signal’ is actively developing more and better targeting systems. This capability is likely to improve over time.

No or limited night capability

Soviet defence industry chose the route of cheap infrared (IR) night viewing systems. Western firms pursued more expensive and technically difficult thermal imaging (TI) technologies. The results were obvious in the Arab-Israeli wars that pitted Soviet kit against Western kit, and in the Iraq wars. Soviet equipment was wholly outclassed.

In the 2000s the Russian Army attempted to catch up, mainly by procuring limited numbers of French TI systems (the same ones bought by the British Army) for its more modern tanks and AFVs. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 and sanctions brought this to an end.

Today, the Russian Army has limited or no night capability, on vehicles or for infantry. It is for this reason that it resembles a WW2 army, only undertaking operations in daylight (night is used for resupply and the redeployment of frontline soldiers between positions).

The standard tactic

The Russian Army attacks. Everyday an average of 170 attacks are mounted. The majority take place on the Pokrovsk front which has been the main effort for months. The attacks involve sending forward small groups of infantry – five and fewer is common – to attempt to make a lodgement in the next treeline or other defensible feature. Heavy jamming and artillery fire can be cues that an attack is about to kick off. Motorbikes and e-scooters are used to evade drones through speed. A blizzard of Russian drones may precede the assault. These so-called ‘meat attacks’ are well named. Failure simply results in repetition (in recent Ukrainian drone footage from the Pokrovsk front, as many as 50 Russian dead can be counted on a short stretch of road). Three recently captured soldiers on this front described a ‘lack of coordination’, ‘meaningless orders’ and ‘brutal rules’. 70% of their comrades had been killed or wounded in a ‘virtually hopeless attack’.

Exploiting an inexhaustible supply of infantry, the probing attacks are repeated regardless of casualties, until eventually an advance is made however small. In cases where survivors achieve an objective but become cut off, resupply of water, food, cigarettes and so on is by drone – withdrawal is forbidden. This can carry on for days and longer.

The reason why this tactic is allowing the Russian Army to creep forward week by week is because Ukraine does not have an inexhaustible supply of infantry and it values the lives of its soldiers.

The officer class

To date, the deaths of 5,432 officers of the Russian army and security agencies had been confirmed. Total Russian fatalities now likely exceed 250,000. What is the story?

In the early stages of the war, a naïve and pumped-up Russian officer class paid a high price for its war enthusiasm: around 10% of all fatalities were officers, including general rank officers. By the end of last year it had dropped to around 3%. Today, only around 1% of fatalities are officers.

After three-and-a-half years of war, Russian officers have revealed themselves to be bullying, corrupt, mendacious and militarily inept. Today, the principal role of the Russian officer is the cynical organisation of the daily conveyor belt of deaths of volunteer kontrakniki.

The soldiery

Who is fighting in Ukraine? Why? There are three groups (the convict cohort once recruited by Wagner PMC has now disappeared). The first group are the survivors of the 300,000 citizens partially mobilised in October 2022. Release from service is by death, or a maiming or other serious injury. Perhaps two thirds survive. The other group are forcibly mobilised Donbas Ukrainians from the separatist areas. Some 100,000 were mobilised. They have been the most abused and recorded the highest desertion rates. The largest group are the volunteer kontraktniki (contract soldiers) lured by bounties and salaries unimaginable in civilian life. The Russian MOD claims over 300,000 kontrakniki sign up every year. Although volunteers are warned they will not be released from service until the war ends, they still sign on believing the conflict will end soon. The majority are unfit, middle-aged men.

Money is a good recruitment sergeant but ineffective on a frontline. From the beginning Russian soldiers have been disgruntled and demotivated. The ‘meat attacks’ have worsened morale. As many as 50,000 Russian soldiers and Donbas Ukrainians have now deserted (a brave decision as the maximum penalty is a 15 year jail term; court records show 18,000 sentences have been handed down). Shocking brutality is now used to enforce discipline, evident in the proliferation of ‘punishment videos’. The last punishment video this author watched involved the electrocution of a Russian soldier. The soles of the feet of the unfortunate, screaming individual had turned black.

Electronic Warfare (EW)

Russian EW Troops were only actually established as a separate command in 2009. Over the next decade five EW brigades, each comprising four battalions were raised. These fielded a range of systems: for jamming, intercept and direction finding. The war has spurred technological evolution and new systems. Today, Russian EW Troops – with Ukrainian counterparts – are probably the most capable in the world.

However, the effects of Russian ECM should not be exaggerated. Every day, Ukrainian drone forces achieve over 700 hits against a range of targets. The drones do get through, on both sides, notwithstanding the saturation of EW systems on the frontlines. Fibre-optic drones, of course, cannot be stopped by ECM.

This van carrying soldiers in a forest near Lyman was fitted with three Niva counter-drone ECM devices (circled). They did not stop the Ukrainian FPV drone making a successful strike. Source: Censor.net

Experienced and capable drone forces

The Russian Army entered the war with nascent rather than developed drone forces. This panorama has utterly changed. The world is witnessing the first drone war in history. The drone arms race between the two combatants has resulted in developments too wide-ranging to summarise in this article. Two points may be made. First, drones now dominate the tactical battle – close and rear. Second, the scale stupefies. On average, Russian forces mount over 3,500 daily drone attacks, or over 100,000 every month. How would the British Army defend against that?

At the time of writing, no NATO army, including the US Army, has credible protection against Russian tactical drones. Only the Ukrainian armed forces have developed a range of defensive measures, through necessity. Once the machinegun was invented it was only going to proliferate. The same is true of the drones. Fibre-optic FPV drone attacks have already been observed from Mali to Myanmar. Nobody can now afford to be without real protection against drones. This is the priority area for the British Army. In this respect, the MOD’s counter-drone initiatives under Project Vanaheim can only be applauded.

Sergio Miller

Sergio Miller is a retired British Army Intelligence Corps officer. He was a regular contributor and book reviewer forBritish Army Review. He is the author of a two-part history of the Vietnam War (Osprey/Bloomsbury) and is currently drafting a history of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.