One hundred years is a defining maxim of time. It is often celebrated, seldom experienced first-hand; long enough to witness significant generational changes, but short enough to be within living memory. This November marked 100 years since the end of the First World War. One hundred years since Western Europe birthed the modern era through a tidal wave of blood and metal. And the Great War did deliver modernity. Not only in the technological advances necessitated by relentless attrition that brought about mechanized warfare so revolutionary that it changed the face of battle irrevocably, but even more so in British society and culture. A society based on creaking Victorian aristocratic values was replaced by what youth was left unspent ushering in the roaring Twenties. Art changed with the arrival of futurism and modernism. Popular music mophed to jazz. Films were broadcast to the population. Literature changed; those who could speak on war opened into a wider field of voices. Culturally, the Great War was a defining event, and also an event that produced great culture. One of the best ways to uncover past events is to investigate the cultural artefacts surrounding it. So, for those who wish to know the Great War, the Wavell Room offers the Wavell Cultural Guide to the First World War.

Fiction

The Regeneration Trilogy by Pat Barker

Based on true life accounts, these three technically separate fiction novels of Regeneration, The Eye in the Door and The Ghost Road form one searing omnibus of the chaos of the front lines, and the psychological toll taken on the people who fought there. She conjures graphic gritty images rich in detail making for visceral, heart-breaking reading; this trilogy is as immersive as it gets. (Image source – Amazon.co.uk).

A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

Written in his singular blistering style, this semi-autobiographical novel of an American volunteer ambulance driver in Italy is both about war and a love story. Don’t be put off by that! The doomed romance between Frederick and Catherine is allegorical of the dualities found in war; masculinity and femininity, violence and calm, hate and love. Hemingway’s way of writing is divisive, he uses the ‘iceberg style’, minimal detail on the surface covering greater meaning beneath. Whether you love or hate that, this is a classic work that brings humanity into the inhumanity of the war. (Image source – Amazon.co.uk).

Non-Fiction

The Great War and Modern Memory by Paul Fussell

Any foray into war writing shows that, despite time soldiers are linked together by the profession of arms. Fussell, a solider in WWII felt that tug of history luring him to explore how previous soldiers experienced the horrors of the first world war. He examined representations of the war from poets, painters, authors, historians and diarists to produce a work that demonstrated how culture changes societies. It is a rare thing; an accessible academic work, rooted not in theory, but in the mud and blood of the trenches. (Image source – Amazon.co.uk).

Goodbye to All That: An Autobiography by Robert Graves

This autobiography is the first and foremost work of prose written by someone who was actually there. Comic, coarse and shocking, it is Graves’s writing on trench warfare that continues to grip 100 years on: “The first dead body I came upon was Samson’s. I found that he had forced his knuckles into his mouth to stop himself crying out and attracting any more men to their death. He had been hit in 17 places.” Essential reading. (Image source – Amazon.co.uk).

Storm of Steel by Ernst Jünger

One thing remarkable about the First World War was the solidarity between combatants. Both British and German soldiers felt a degree of sympathy and kinship that transcended enmity. Storm of Steel is a strangely jaunty presentation of a young German officers experiences on the Western Front. Useful for seeing that soldiering is soldiering no matter what side is fought for. (Image source – Amazon.co.uk).

Film

All Quiet on the Western Front 1930

Based on the best-selling novel by Erich Maria Remarque, this drama is about young German soldiers growing disillusioned with the war. Provocative and anti-war, it remains a technical masterpiece and a nightmare vision of a war without glory. See the trailer here. (Image source – gointothestory.com).

Gallipoli, 1981

You can’t fully appreciate the impact of the First World War without looking at the underbelly attack on ‘the sick man of Europe’, the Ottoman Empire, through the taking of the Dardanelles. This campaign spearheaded by Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, intended to break the stalemate on the Western Front, but instead ended in catastrophic failure. Peter Weir’s classic film portraying the plucky, dogged ANZAC soldiers captures how the national identity of Australia in particular was forged. Gallipoli, more than any other engagement of the time highlighted the absolute necessity of the operational level in war, and what happens when strategy isn’t translated into tactics. (Image source – arthipo.com).

Paths of Glory, 1957

Arguably Stanley Kubrick’s first work of genius, the Paths of Glory is worth the watch just for the iconic scene where Kirk Douglas’s French commander Colonel Dax stalks down the trenches, imperious despite the shell barrage taking place. The film tackles the thorniest of subjects, cowardice in war, the punishments dealt out, the waste of life, and command under such conditions. It makes the point that the ‘paths of glory lead but to the grave’. (Image source – rogerebert.com).

Television

Blackadder Goes Forth

Some accuse this series of trivialising a topic totally inappropriate to comedy, but to many Blackadder walks a perfect line between satire and pathos. It mercilessly captures the enduring idea of ‘lions led by donkeys’ and the ineptitude of the British high command safely sat drinking Bordeaux in Chateaus. Although this stereotype is now considered inaccurate given the reality was more complicated, Blackadder summed up every piece of battlefield folklore from the time. The tragic end of the final episode was so unexpectedly moving it sealed the legacy of a show which continues as a source of scholarly, and political debate. (Image source – bbc.co.uk).

They Shall Not Grow Old

There is a fear that technology will oblitrate our humanness, eradicate our connection to each other. They Shall Not Grow Old shows the opposite, that technology is not removing our humanity, but helping us get in touch with it. There’s always been a sense of removal in footage of the WWI. Grainy, jerky movements of people resembling marionettes more than flesh and blood, seen in a washed out sepia that detaches mind and soul from what your eyes see. We have had to rely visually on movie magic to generate a feeling of ‘being there’ in the trenches, to really identify with those who were there. Peter Jackson’s film changes all that. The moment when the screen opens up and we telescope into the picture, it becomes not just technicolour but living colour, puppets become men, what was obscured by the technology of its time is brought into present and you are flung into the past. There is a particular sobering poignancy in the recognition of soldiers being soldiers for any military person. Jackson used cutting edge digital techniques, lip-reading experts, and actors dubbing back in words long lost in a phenomenally painstaking endeavour. But more than that, this film creates an aperture where we not only see, but feel the past in the present, and for that alone this breath-taking film deserves every bit of praise it got.

Art

Gassed by John Singer Sargent, 1918

When the British Government commissioned Sargent to produce a painting for a Hall of Remembrance they probably didn’t envision something like this. The nine x 21 foot panoramic scene of gassed soldiers being led to a medical dressing station is both literally, and figuratively enormous. The New York Times called Gassed ‘monumental’, the Telegraph said ‘it is magnificent and harrowing’; it manages to capture the whole war in one picture. See it for yourself at the Imperial War Museum, London when it returns from its North American tour later this year. (Image source – IWM).

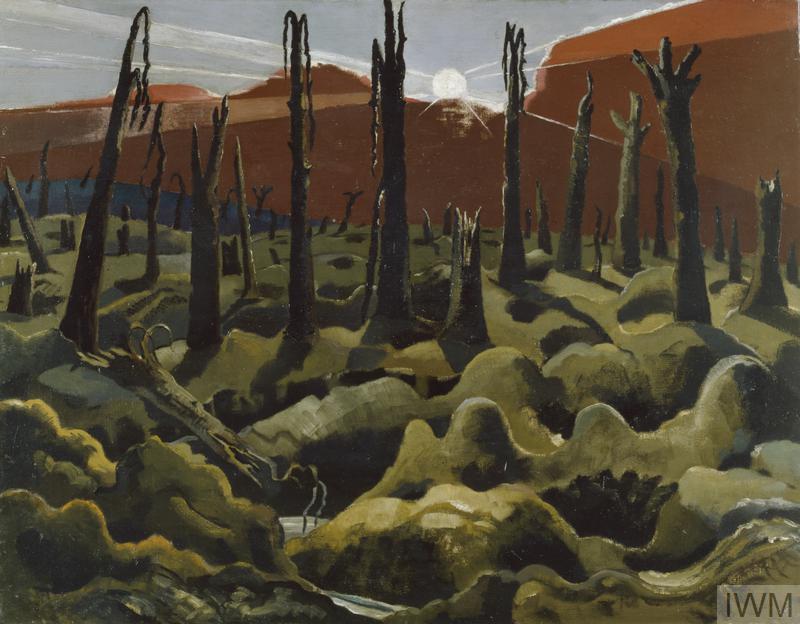

We are Making a New World by Paul Nash, 1918

Another official war artist, Paul Nash produced a bleak vision of the sun rising on the new world, a hell-scape devoid of life; the image a contrast with the optimistic title. It is his avant-garde style of Cubism and surrealism so despised by conservative factions in Britain that symbolises how this war changed the way human life is captured in art. (Image source – IWM).

Poetry

The War Poets

Poetry is probably the cultural form most brought to mind when thinking of World War One. Literate soldiers, officers, nurses, and journalists, reached for words to express their experiences, words which stood in stark contrast to the propaganda being shown back home. Sigfried Sasson, Wilfred Owen, and Rupert Brooke are the most famous names but a delve into poetry of the era reveals a plethora of lesser known writers. However, for a quick lesson on how brevity can still speak volumes see the classics, Suicide in the Trenches, Anthem for Doomed Youth, and of course, that old li, Dulce Et Decorum Est.

Image – Doomed Youth, from left to right; Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. Image sources – the Rupert Brooke Society, Wikipedia, and the British Library).