TL:DR

The British Armed Forces lack a clear vision and positive sense of purpose. I will explain how the world shall change over the coming decades, and how the Armed Forces currently find themselves poised to respond to this change. Finally, I propose ways in which the Armed Forces might be reconceptualised to guarantee a more just future, for both the UK and the world.

Introduction

‘What would you think of a man who not only kept an arsenal in his home, but was collecting at enormous financial sacrifice, a second arsenal to protect the first one? What would you say if this man so frightened his neighbors that they in turn were collecting weapons to protect themselves from him? What if this man spent ten times as much money on his expensive weapons as he did on the education of his children?’1

In a previous article, I discussed deficiencies in the British Armed Force’s approach to leadership and analysed how the Integrated Review (IR) appears likely to lead to moral failure as a result. I focussed on the potential for architectural and market forces to counteract all but the most powerful pressure from social norms and legal obligations (or, to use another theory, how the base comes to ultimately dominate the superstructure). This is only half of the equation, and in this article, I would like to explore the other half. Understanding of either alone is insufficient; understanding of both is vitally necessary.

First, I argue that the British Armed Forces lack a clear vision and positive sense of purpose. I then try to anticipate how the world shall change over the coming decades, and how the Armed Forces currently find themselves poised to respond to this change. Finally, I propose ways in which the Armed Forces might be reconceptualised to guarantee a more just future, for both the UK and the world.

Our Unique Selling Point

To begin, we must be prepared to consider the core question about just what the British Armed Forces are for. What is it that makes the British Armed Forces unique, compared to the many other assets at HM Government’s disposal?

Despite the title, the British Armed Forces have never been a uniquely armed force. As late as the 19th century, the populace itself routinely carried arms, as did the police; the latter continue to do so in the form of authorised firearms officers up and down the country. Neither do the British Armed Forces have a claim to be a uniquely extra-territorial force. The UK has no equivalent to the United States’ Posse Comitatus Act (which forbids federal military personally from enforcing domestic policies within the country) and, under the guise of Military Aid to the Civil Authorities, personnel from all three Services provide domestic support in roles ranging from mountain rescue, bomb disposal and Op TEMPERER to the COVID Support Force and tanker driving under Op ESCALIN.

Are the British Armed Forces uniquely expeditionary, in the sense of operating overseas in support of British interests? No, the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) in the guise of MI6 occupies the same role. But the SIS is a chiefly civilian, intelligence-gathering agency. Is the unique selling point of the British Armed Forces therefore its authority to commit violence overseas? Again, no; SIS agents can be authorised by the Foreign Secretary to do so too, and intelligence operatives more broadly are able to commit many more crimes besides. However, the nature of spycraft is that ‘everything we do overseas is illegal [so] we’re at the mercy of the lawmakers in the country we’re operating’.

So, it would appear that the unique purpose we are left with for the British Armed Forces as a whole (i.e., not including those unique roles fulfilled by a relatively small number of assets, such as air defence and nuclear deterrent) is a) the deployment of violence b) at scale c) overtly d) overseas e) in line with international law and f) the laws of the nation in which the violence occurs.

This is not a particularly inspiring calling, and as discussed in my previous article almost every element of it will be challenged by proposed reforms. I conclude, therefore, that three centuries of change have left the British Armed Forces adrift and without a clear purpose. This is a situation that can only be obscured by jargon for so long.

The British Army, for example, describes itself as ‘primarily a war-fighting organisation’, and the profession of arms is itself defined sociologically as the ‘management of violence’.2 Despite this, the Army lists ‘fight[ing] the nation’s enemies’ last in its list of ‘what we do’ on its own website, and even then insists it will do so only ‘in extremis and when called upon’. This reticence, coupled with the growing global influence of ideas such as the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), makes it difficult not to feel as though the Army, and Defence more broadly, is grasping for something greater.

The Coming Storm(s)

It should not be controversial to state that the 21st Century is going to be a challenging one, the dominant feature of which is sure to be the continuing effects of climate change.3 It is worth nothing at this stage that the Ministry of Defence is itself a major polluter, though its emissions are exempt from mandatory reporting under various climate change agreements. The effects of this will not be uniformly distributed across the globe. Today, 1 in 97 people on the planet are displaced, and climate change has well-documented links to conflict. The startling statistic of 1 in 97 is only going to increase, as climate change-induced human migration becomes the defining humanitarian crisis of the coming century. Naturally, people will seek out safer and more habitable climes, Britain amongst them.

Anticipating this, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has already issued legal guidance stating that ‘people fleeing in the context of the adverse effects of climate change and disasters may have valid claims for refugee status under the 1951 Convention [relating to the Status of Refugees]’. This guidance has been reinforced by human rights rulings. Concurrently, and at odds to the UN’s guidance, the UK has for almost a decade operated a ‘hostile environment’ policy towards asylum seekers and refugees.

Whether by holding people indefinitely in concentration camps deemed unfit for human habitation and failing to properly investigate deaths in custody, abruptly cutting off already-paltry subsistence payments or implementing an Australian-inspired boat push-back policy, successive governments have repeatedly and flagrantly breached their obligations towards asylum seekers and refugees under both domestic and international law. As the IR openly—and ominously—declares, the UK government feels that the ‘rules-based international system…is no longer sufficient for the decade ahead’ that it ‘must be more active in shaping the international order of the future.’

‘Daddy, what did YOU do…?’

The British Armed Forces will find themselves at the frontline of any such shaping efforts, and so it is crucial to consider what we may find ourselves asked to do on behalf of ‘Queen & Country’. In happier times, for example, one might imagine the role of managing the nation’s response to desperate people crossing a dangerous shipping route would go to someone from a humanitarian background, but in our times the role goes to an ex-Marine and comes with the grandiose title of ‘Clandestine Channel Threat Commander’. At the same time, the Home Secretary has floated the idea of directly using the Navy in such operations, and a contingent of Royal Engineers will have the opportunity to gain valuable wall-building experience on the Poland–Belarus border as refugees freeze to death in the forests beyond.

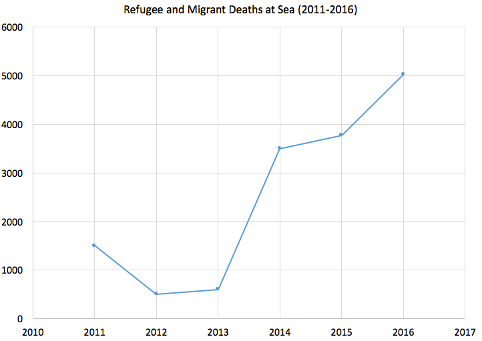

The militarisation of border control pre-dates our exit from the EU, with the Royal Navy having previously deployed vessels alongside other EU nations as part of Op SOFIA, an operation ostensibly meant to combat people smuggling and prevent loss of life in the Mediterranean. SOPHIA lasted for 5 years before being closed down in 2020, after which a report by the House of Lords concluded that SOPHIA had ‘not in any meaningful way deterred the flow of migrants…or impeded the business of people smuggling on the central Mediterranean route’, but had led ‘to an increase in deaths’.

SOPHIA was part of the EU’s wider ‘Fortress Europe’ ideology, which also saw them replace lifesaving search-and-rescue operations in the Mediterranean with border security operations that led, within a year, to a 1,600% increase in migrant deaths and the emergence of a thriving slave trade in Libya. Relations with the EU may be strained at present, but it is clear that we can still find common ground when it comes to brutal border policy. Why?

‘A Europe of camps’

The IR announces that ‘the Government’s first and overriding priority is to protect and promote the interests of the British people through our actions at home and overseas’; specifically, their interests of ‘sovereignty’, ‘security’ and ‘prosperity’. Echoing this, the Ministry of Defence mission statement declares that ‘We work for a secure and prosperous United Kingdom with global reach and influence. We will protect our people, territories, values and interests at home and overseas, through strong armed forces and in partnership with allies, to ensure our security, support our national interests and safeguard our prosperity.’ Meanwhile, the UK Government cuts its foreign aid spending.

‘Depending on the nature of external challenges,’ writes Lionel Fatton, ‘government leaders call on different domestic entities to participate in the formulation of foreign policy [and] they must ask for the expertise of specialized institutions in order to understand issues at hand’. Each of these institutions will have its own logics and biases, and when ‘leaders perceive other countries as hostile and national security as endangered…the biases of the military affect government leaders.’

According to Fatton, ‘the most pronounced military bias is the tendency to adopt worst-case analyses…often leading to exaggerations of external threats’.4 Faced with the inexorable threat of climate change, the analytical line taken appears to be thus: many will suffer and die in the decades to come, but provided the bodies are piled up outside our island fortress—out of sight, out of mind—all will be well.

Achille Mbembe defines this state of affairs as ‘necropolitics’, or the idea of sovereignty as ‘the capacity to define who matters and who does not, who is disposable and who is not’. The IR declares that our sovereignty must be protected. The resulting Armed Forces reconfiguration suggests that such protection will come from shadowy operatives capable of doing unspeakable acts (vide the Greeks and the Americans) in unknown countries, all paid for by us and notionally operating on our behalf; our security and prosperity, all provided at the expense of the Other, unseen except for when their bodies wash up our shores.

In an increasingly Balkanized and isolated world, where are the most deadly migrant routes? It is Europe! Who claims the largest number of skeletons and the largest marine cemetery in this century? Again, it is Europe! The greatest number of deserts, territorial and international waters, channels, islands, straits, enclaves, canals, rivers, ports, and airports transformed into iron curtain technologies? Europe! And to top it all off, in these times of permanent escalation—the camps. The return of camps. A Europe of camps. Samos, Chios, Lesbos, Idomeni, Lampedusa, Vintimille, Sicily, Subotica[, Yarl’s Wood, Harmondsworth, Napier]—the list goes on.5

Aching for Something More

When the IR insists that ‘the UK will continue to play a leading international role…in keeping with our history’, it fails to say why we should consider this desirable. Britain’s history, after all, is a deeply grey chronicle, part and parcel of a global imperial dominance that necessitated the subjugation of countless peoples.

Historically, our ‘leading international role’ has seen us: establish and benefit from the trans-Atlantic slave trade and then contribute to its abolition; first appease and then combat fascism in Europe; spread democratic ideals and introduce resilient legal systems; cause and exacerbate famines; and carve lasting scars into the Middle-East, the consequences of which continue to reverberate today. It is not at all clear that Britain playing a ‘leading international role’ is an inherently good thing for the world; only that it can be, should we choose for it to be so.

‘There is an eschatology to current affairs’, writes Shane Burley, but ‘in this moment of crisis, we can choose how to respond, with solidarity or barbarism’.6 We are not obliged to pull the ladder up behind us, to retreat behind our walls of our island fortress and pretend not to notice the stench of death from outside. Given the right direction, I firmly believe that the British Armed Forces, and Britain as a whole, can be a potent force for good in the world: just ask the Kuwaitis, the Kosovars or the West Africans.

I believe that the British Armed Forces, with their vast reserves of money, materiel and highly-trained, highly-motivated personnel, could well be one of the most effective humanitarian organisations in history. In my more optimistic moments, I even think that the pendulum may well be swinging that way.

The Ebola Medal for Service in West Africa, established in 2015, is the first UK medal to be awarded for a humanitarian, rather than a military, crisis response, and could well presage a more permanent shift of priorities. And yet, a recently-published collection of essays from RUSI examining how Britain may become a force for good in the world includes only two brief mentions of the Armed Forces, in the contexts of training foreign security forces and contributing to UN peacekeeping missions. My concern is that the IR risks halting any such swing, or even reversing it.

Don’t get me wrong: the IR does accurately describe a world of genuine dangers, from increasingly aggressive great powers and information warfare to international terrorism and climate change. ‘It is within this context that the state is trying to remain relevant as the communal security provider…The state, which developed into the monopolist on violence during the nineteenth century, needs to justify its existence by delivering on people’s security needs.’7

However, there are many routes to achieving security, and projects like the Alternative Security Review are exploring these. It is unfortunate that the IR has concluded, courtesy of the militarised logic through which it has been conceived, that the best approach is business as usual, despite its spotty track record. We know, for example, that our approach to terrorism simply does not work. After the first decade of the now two-decade-long ‘War on Terror’, the FBI announced that ‘the United States faces a more diverse, yet no less formidable, terrorist threat than that of 2001’. The former Director General of MI5 concluded in the same year—long before anyone had even heard of Daesh—that ‘terrorism…could not be solved militarily’, and a 2008 RAND study found that only 7% of terrorist groups surveyed were ended by military force. And yet the IR will have us continue as before, throwing good money after bad.

We must move beyond ‘postcolonial melancholia’, which Mark Fisher characterised as not ‘(just) [a] refus[al] to accept change [but] at some level, [a] refus[al] to accept that change has happened at all’, whilst ‘incoherently hold[ing] on to the fantasy of omnipotence by experiencing change only as decline and failure…’.8 At the same time, we must learn from Op SOFIA that simple attempts to use the Armed Forces in their current form in humanitarian contexts is akin to trying to perform surgery with a broadsword. Whilst the values of the various Armed Forces are worth preserving, the structures must be fundamentally changed.

Who Could We Be?

Allow me to conclude by indulging in some radical thinking, with apologies to John Lennon.

John Lennon Wall (courtesy of elPadawan – Flikr)

Imagine a Britain that accepts that the world has moved on, that the Empire is never coming back (nor should it) and that is happy to settle into a dignified national old age as what the IR calls a ‘middle power’, rather than continuing to engage in ‘neo-Victorian’ fantasy. Imagine a Britain that, contrary to the belief that it ‘lacks the agency to be…morally stubborn no matter how much it believes in its own virtue’, proudly wears its rejection of the ruthless and pointlessly cruel realpolitik that dominated the previous century as a badge of honour.

Imagine that we may begin with a blank slate upon which there exists no British Armed Forces, and that we may ignore for a moment the exigencies of vested interests, the awesome power of the military-industrial complex and the tonnes of historical baggage we would have to deal with in reality.

Imagine a Chief of the Defence Staff coming from a medical or even chaplaincy background, rather than a combat or combat support one, and that this seemed not just plausible but even desirable. Imagine that, instead of conceptualising the Armed Forces as composed of ‘teeth’ arms and their supporters, you imagined it as the ‘humanitarian’ arms and their protectors. Imagine if, rather than the bare ‘management of violence’ in the service of ‘protect[ing] our prosperity’, you aspired to the ‘abolition of violence’ in the service of ‘protecting all prosperity’.

If you had this blank slate, what might you create in its stead? How would you constitute a body that was responsible for ensuring the protection of the UK and its people from threats without—how would you envision a genuine British Defence Force?

Would it be a force that does not aspire to meddle in the great power political games of others, but instead adopts a more neutral stance (a la the Finns or the Kiwis)? Would it be a force that tries to quietly improve the condition of the world, trusting that its good example will exert a positive influence without any undue effort?

Would it be a force that recognises that true internationalism—not just the NATO kind—is required in the face of the planetary-scale problems to come, and which endeavours to resolve issues at their roots, far away from the homeland, rather than merely manning the barricades in a doomed effort to keep the consequences at bay? Would it be a force with a strong moral compass and lines it considered uncrossable, serving a government that chose its friends based on shared respect for human rights and ethical conduct, rather than fleeting strategic advantage and the prospects of arms sales?

Would it be a force restricted in how and where it could operate? Consider Smedley Butler’s proposal that ‘the ships of our navy…should be specifically limited, by law, to within 200 miles of our coastline…and the army should never leave the territorial limits of our nation’? Would it be constitutionally prohibited from ‘the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes’, as the Japanese Self-Defense Forces are? Would you be so bold as to abolish the standing army altogether, as Costa Rica did, and celebrate the date of abolition as a national holiday?

Perhaps you might consider the materiel and manpower better utilised in a civil defence role such as that of the German Technisches Hilfswerk, leaving the playing of soldiers to young boys and old men? Would the workforce be unionised, as the Danish soldiers are, or would it incorporate a Veterans for Peace chapter alongside the existing Defence support networks to act as an ‘ethical auditor’,9 challenging the predominant biases inherent to military thinking? Or perhaps you would forge an entirely new path, one for which there are neither historical antecedents nor contemporary peers to compare with, but potentially an entire world to win?

Becoming a ‘soft power’ force does not mean becoming soft. It means consciously choosing to reject the application of violence, skilful or otherwise, as a valid or effective means of affecting change in the world. It means having confidence in the strength of our values and trusting that others will be unable to deny the results they bring. It means having the courage to be open to scrutiny and to accept criticism.10 It also means architecting our systems in a way that will promote positive behaviour and expose failure and to accept responsibility when things go wrong.11

‘If we have faith that the internal issues [that face this Army] will be sorted,’ wrote the editor of the British Army Review in 2018, and ‘that a new Army will emerge from all the changes then perhaps we can cast aside the current worries and think about the hope the British Army [and the wider Armed Forces] can bring to those who are crying out for it.’12

I mentioned my youth in the introduction to my first article, and I will conclude this one by primarily (though by no means exclusively) addressing my generational peers. Do not forget that the decisions made today will define the world that we will have to live in, just as the decision to invade Afghanistan twenty years ago defined the world we have grown up in, and the decision to arm the mujahideen defined the twenty years before that.

We must imagine the kind of world we want to be living in twenty years from now and determine how best to get there. If, as I’ve suggested, Defence is striving for a greater purpose, we must be the ones to articulate what that could be, and to push Defence towards it.

‘Every happy man should have someone with a little hammer at his door to knock and remind him that there are unhappy people, and that, however happy he may be, life will sooner or later show its claws, and some misfortune will befall him — illness, poverty, loss, and then no one will see or hear him, just as he now neither sees nor hears others.’13

Ben

Reservist for just shy of a decade, mostly in and around the Army Medical Services (AMS). International humanitarian law geek. Writing in a personal capacity; all opinions are my own and do not reflect those of my employers, colleagues or any affiliated groups.

Footnotes

- R. Shea and R.A. Wilson, The Illuminatus! Trilogy, Raven Books, 1998, 367

- Samuel P. Huntingdon, The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations (Belknap Press, 1981), 11

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s most recent report (https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/) predicts that ‘global surface temperature will continue to increase until at least the mid-century under all emissions scenarios considered [and that] global warming of 1.5°C and 2°C will be exceeded during the 21st century unless deep reductions in CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions occur in the coming decades’; he UK is currently on track to achieve only a third of its target reductions (https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/2021-progress-report-to-parliament/) and the recent COP26 agreement failed to guarantee the goal of keeping temperature rises below 1.5°C. (https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/13/cop26-the-goal-of-15c-of-climate-heating-is-alive-but-only-just).

- Lionel P. Fatton, ‘The Impotence of Conventional Arms Control: Why do international regimes fail when they are most needed?’ Contemporary Security Policy 37 (2016): 200-222

- Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics, (Duke University Press Books 2019), 102

- Shane Burley, Why We Fight: Essays on Fascism, Resistance, and Surviving the Apocalypse, (AK Press, 2021), 108–109.

- Andreas Krieg and Jean-Marc Rickli, Surrogate Warfare: The Art of War in the 21st Century, Defence Studies 18, Issue 2 (2018): 118-130.

- Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (Zero Books, 2014), 24.

- Maj Tom McDermott, “Taking Action” in ‘Armouring Against Atrocity’ (12:19–12:32)

- It is worth pointing out that, at least in my experience, the Army generally does this well in certain areas (such as diversity and inclusion), but not in others (https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/aug/22/britain-military-failure-afghanistan-campaign).

- Research shows that even the mere threat of exposure can be a powerful deterrent, and that ‘…extreme behaviours can be restrained by rendering actors visible, and hence accountable, to broader or yet-to-be encountered audiences’ (“Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC prison study”).

- Graham Thomas, ‘Hope’, British Army Review 172, Summer (2018): 20-22.

- Anton Chekhov, Gooseberries.