One of the most vexing tasks faced by leaders in democracies is the challenge of dealing with dangerous generals. Not all generals have the potential to be truly dangerous; it is a function of position and behavior. The category of generals who possess the potential to be dangerous is restricted to those who are senior commanders or avatars of a state’s war-making ability. In World War II, Eisenhower was an example of the former and Patton was an example of the latter. These generals have the potential to be considered dangerous once they exhibit repeated incompetence or some other behavior that threatens the interests of the state.

The challenge of dealing with dangerous generals is not simply an exercise in civil-military relations. In a larger sense, it is relevant for any 21st century organizational leader because the relationship between political leaders and military commanders is one of governance. The military and political worlds have faced the problem of governance for much longer than the corporate world and lessons learned from civil-military relations have broad relevance to all sorts of governance relationships. How much latitude should be given to military leaders by those designated as their guardians? How can it be expected that guardians from one profession (such as political leaders) will have the expertise to oversee leaders from another profession (such as generals)? Politicians and generals have wrestled with these issues for centuries and their accumulated experience has value to leaders in all sorts of professions.

This article will consider two generals who were considered dangerous by their respective political leaders – General Sir Douglas Haig, who commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) for most of the First World War and General Douglas MacArthur, who commanded United Nations forces during the first year of the Korean War. These cases are instructive at several levels. These two generals were considered dangerous by their political leaders for completely different reasons. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George saw Haig as a danger because he considered his battlefield performance to be unsatisfactory. In the Korean War, American President Harry Truman gradually came to consider MacArthur a danger because of MacArthur’s constant and increasingly public insubordination. It is also instructive that these two generals experienced completely different fates. In the final two years of World War I, Prime Minister Lloyd George actively sought to dismiss Haig, yet the war ended with Haig still in command of the British Expeditionary Force. The American case had a completely different outcome. Unlike Haig, MacArthur did not survive the wrath of his commander in chief and he was fired by President Truman ten months after the Korean War began.

Lloyd George and Haig – Dealing with a general who had the ear of a king

David Lloyd George and Douglas Haig were a textbook study in contrast. They came from different backgrounds and possessed different temperaments, but what is most significant is that they had completely different views on wartime strategy and civil-military relations.

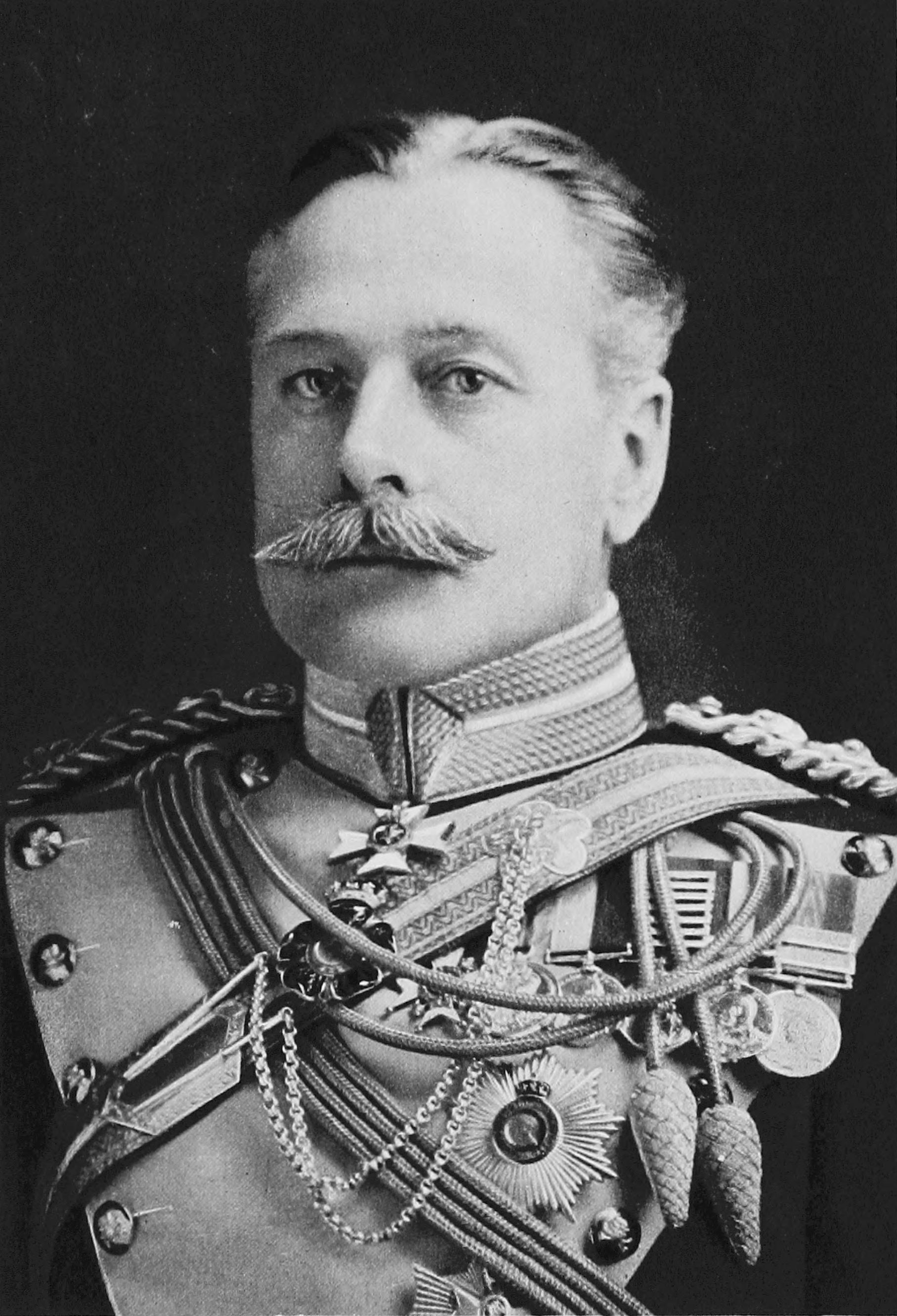

A life-long cavalry officer who exuded self-confidence and unflappability, Douglas Haig was born into a socially elite family of wealth and privilege. During his early Army career, which included service in the Sudan, the Boer War, and India, he rarely set a foot wrong. In addition, due to family connections, he became friends with two British kings – Edward VII and his son, George V. When Sir John French was fired as commander of the BEF in the winter of 1915, it surprised no one that Douglas Haig was chosen as his replacement. Haig remained as the commander of the BEF for almost three years until the war ended in November 1918.

David Lloyd George grew up in a small cottage in Wales and became active in politics when barely out of his teens. He had the gift of political charisma and public eloquence and served in Parliament for more than fifty years. As a young member of Parliament, he criticized British generals fighting the Boer War and later, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he criticized British admirals for their “reckless” budgetary decisions. Given this background, it is perhaps ironic that he became the Secretary of State for War in 1916 and subsequently spent the last two years of the war as Prime Minister.

When Lloyd George became Prime Minister, the three most powerful British military commanders were Admiral John Jellicoe (First Sea Lord), General William Robertson (Chief of the Imperial General Staff) and General Douglas Haig. All three of these military men had surprisingly similar disagreements with Lloyd George and by the beginning of 1918, Lloyd George had gotten rid of two of them. Jellicoe, Robertson, and Haig shared several perspectives on the war. All three of them defined civilian involvement in military affairs as “interference” and all three wanted a single focus on the Western Front as opposed to Lloyd George who wanted to expand the war to regions such as the Middle East, the Balkans and Italy. Moreover, all three had fundamental disagreements with Lloyd George over the nature of military operations in their respective spheres. In the case of the Admiralty, Lloyd George’s problem was the existential threat that German U-boats posed to the British Isles and the fact that Admiral Jellicoe refused to establish a convoying system to combat this threat. Jellicoe would continue to drag his feet on the use of convoys until forced to do so by Lloyd George in the spring of 1917.1 For all of the above-stated reasons, Lloyd George had Jellicoe fired in December 1917.

In the case of the Army generals, Haig (enabled by Robertson) continued to carry out military operations on the Western Front that were as bloody as they were useless. In the Somme offensive of 1916, the BEF suffered 125,000 killed in action and this battle has been described as the greatest military tragedy in British history.2 To place this horrific loss in context, the Somme offensive, by itself, equated to roughly one-third of all British military deaths in World War II. And the Somme was no anomaly. It has been estimated that more than half of all British soldiers sent to Haig in France were either killed or wounded in action.3. During the year of the Somme offensive when he was still War Secretary, Lloyd George revealed his sense of revulsion at the bloody state of affairs on the Western Front when he remarked to a friend that “I am the butcher’s boy who leads in the animals to be slaughtered”.4 As a politician, Lloyd George’s perspective on this carnage was that it could not continue without inflicting unacceptable costs on British society, culture and the economy. As a soldier, Haig’s perspective on this horrific level of carnage was that it was acceptable as long as the British were inflicting an even greater level of casualties on the German army.

By the beginning of 1918, one military historian summarized Haig’s record as follows, “his best-laid plans had failed… his army was demoralized, the press no longer trusted him… the Prime Minister was trying to isolate and replace him and the initiative on the Western Front was in German hands”.5 By February 1918, Lloyd George had forced General Robertson to resign but Haig survived Lloyd George’s best efforts and remained in command of the BEF until the end of the war in November 1918.

It is appropriate at this point to emphasize that this article is not intended to be the final word on Douglas Haig’s military competence in the eyes of history. Historians have pointed out that the quality of World War I generalship is one of the most hotly debated subjects in the field of military history and Haig’s reputation has certainly waxed and waned over the last century. What is relevant here is to point out that David Lloyd George did not have the luxury of waiting until history rendered a final verdict on Haig’s competence. As Prime Minister, he had to form a personal judgement about Haig in 1917 and act accordingly.

It is plain that Lloyd George considered Douglas Haig to be a “dangerous general” for a variety of reasons and, as a consequence, sought to replace him. The contentious relationship between these two men provides several relevant insights into the challenge of governance. First of all, it is interesting that Haig was able to survive in his position during the war despite the unrelenting hostility of Lloyd George. It is also interesting to see that Lloyd George developed a series of options for dealing with Haig once he realized that he did not have the political power to dismiss his BEF commander. As we will see, Lloyd George launched two completely different indirect attacks on Haig in order to establish some degree of governance and to limit Haig’s ability to influence the conduct of the war.

There are several reasons why Haig survived as commander of the BEF despite the efforts of Lloyd George to limit his influence and replace him. The most basic reason is that Haig looked and acted the part of a great commander and millions of Britons, conditioned by the historical examples of Wellington, Wolseley and Kitchener, considered Haig as the heroic personification of the British war effort. In fact, after the war, Haig remained very popular with the British public and he was widely mourned when he died in 1928. Attempting to fire Haig during the war would have been difficult and would have involved an unacceptably high political cost for Lloyd George and his coalition government.

A network of allies

Haig’s escape from Lloyd George’s displeasure was also due to a very effective defense mechanism at Haig’s disposal. Throughout Haig’s career, he was able to build and maintain a powerful network of allies, which eventually included the King, conservative politicians and powerful press barons. Haig’s relationship with King George V was so close that Haig felt perfectly comfortable sending letters to the King in which he was strongly critical of (then) BEF commander Sir John French and Prime Minister Lloyd George. As a result of his social network, when Haig made his pronouncements about the conduct of the war, they resonated loudly in the British political establishment.

Douglas Haig eventually came to be considered as a dangerous general who could not be fired but this situation forced Prime Minister Lloyd George to develop a set of alternatives to establish a degree of control. Once Lloyd George realized that he did not possess the power to remove Haig, it occurred to him that an acceptable course of action would be to take steps that would significantly limit Haig’s effects on the British war effort. He worked to achieve this goal by following two different courses of action. First, he adopted the line of logic that dictated that Haig would produce fewer casualties if he had fewer soldiers under his command. Beginning in 1917 Lloyd George and his government began to actively reduce the number of men drafted for the British Army. As one historian put it, “Manpower policy was used as a weapon… to force upon Haig less costly tactics and a more cautious strategy”.6

In addition to limiting the size of the force under Haig’s command, Lloyd George worked to limit the scope of Haig’s authority. He helped create the Supreme War Council in the fall of 1917, which ostensibly was to coordinate Allied military activity although in the words of one historian, Lloyd George’s real motive “was to wrest control of the British strategy from Robertson and Haig”7 In addition, Lloyd George worked to create a supreme commander with authority over French and British military operations and in the spring of 1918, French General Ferdinand Foch was given the title “Supreme Commander of the Allied Armies.” Haig strongly objected to this arrangement but Foch’s appointment had the approval of the British government so he was forced to go along.

There are several governance lessons from our First World War example. From Haig’s point of view, it is clear that strategic leaders benefit by having robust social networks. Social network theorists argue that social networks are a valuable source of information, validation and credibility but in Haig’s case we see that social networks can be effectively used as a defense mechanism. The fact that the King of England and the owners of powerful newspapers were active supporters of the embattled general was essential to Haig’s survival as commander of the BEF.

From Lloyd George’s point of view, the governance lesson is that strategic leaders always need a strategy for their strategy. Lloyd George and Haig had very different ideas about winning the war. Haig focused on operational plans designed to defeat the Germans on the battlefield. Prime Minister Lloyd George did not have the luxury of focusing on one aim as Haig did. Lloyd George needed a strategy that defeated Germany while preserving British public support and placating his French allies. Once Lloyd George realized that he could not get rid of Haig, he eventually decided to minimize Haig’s resources (fewer soldiers) and limit Haig’s authority (appoint a French commander-in-chief of the Allied armies). These actions were used to achieve his goals by limiting Haig’s ability to develop ruinous campaign plans.

Truman and MacArthur – dealing with a general who rarely heard “no”

Douglas MacArthur lived a completely military life. His father, Arthur MacArthur, was a Civil War hero and Medal of Honor winner who was Governor-General of the Philippines late in his career. The Philippines had come under American control after the Spanish-American War and it is interesting and somewhat relevant to mention what happened when General Arthur MacArthur was military governor of the Philippines in 1900. When the McKinley Administration decided to transition the Philippines to civilian control, MacArthur clashed repeatedly with members of the U.S. government commission who had come to replace him. At one point, he told a startled commissioner named William Howard Taft that President McKinley didn’t have the constitutional authority to limit his military rule of the Philippines. The friction continued and an irritated Taft finally complained to the War Department that MacArthur was treating the civilian commissioners “exactly as he would any subordinate”.8 Several years later, Arthur MacArthur ended his military career in disappointment when this same William Howard Taft, who was now Secretary of War, passed over MacArthur when it came time to appoint a new Army Chief of Staff. It almost seems as if both MacArthurs shared the same genetic hostility towards civilian authority.

General Douglas MacArthur ended World War II as a national hero and his prestige was such that President Truman selected him (instead of Admiral Nimitz) as the logical choice to receive the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay. In a move that had unforeseen and unfortunate implications for the Truman Administration, MacArthur spent the five years between the end of World War II and the beginning of the Korean War as the supreme ruler of Japan. In August 1945, President Truman asked MacArthur to become the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP) in Japan. As such, he exercised absolute authority over the Japanese government and the Emperor of Japan. This power relationship became apparent for the world to see when MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito met for the first time. The official photo of their meeting shows Hirohito standing at attention, formally dressed in morning coat, waistcoat and striped trousers. MacArthur appears studiously casual in his workday, open-necked khaki uniform with no ribbons or medals. The photo makes the point that MacArthur considered himself the equal of a national leader and this attitude would manifest itself later in his relationship with President Truman.

During his time in Japan, MacArthur had an active, transformative and positive effect on Japanese politics, society and its economy. He was outspoken about rights for Japanese women and instrumental in the creation of the postwar Japanese constitution. And he accomplished all of this in a way that made him immensely popular in Japan. When Japan was welcomed back into the community of nations at an international conference in 1951, it was commonly recognized that this success was in great part due to MacArthur’s efforts. To understand MacArthur’s behavior during the Korean War, it is important to remember two things. First, he spent the five years leading up to the Korean War as the ruler of Japan where no one ever told him what to do and secondly, he fulfilled this historic role in an outstanding manner.

When the Korean war began in 1950, MacArthur had been a soldier for almost 50 years and he had definite ideas about how to win this unforeseen conflict. MacArthur operated under the loosest of supervision because of his operational brilliance in the early, dark days of the Korean War. With his army initially beaten back into a small corner of the Korean peninsula, MacArthur quickly conceived a daring plan. Despite strong objections from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, he flawlessly carried out a complex and risky amphibious landing far behind enemy lines at Inchon. His stunning success completely and quickly transformed the nature of the war but his success came with a tragic price. The victory at Inchon greatly inflated MacArthur’s belief in himself while it made the Joint Chiefs much more hesitant in their efforts to restrain him.9 A few months after Inchon, when MacArthur had become even more difficult to manage, a senior Army general remembers asking one of the Joint Chiefs why didn’t the Joint Chiefs simply “send orders to MacArthur and tell him what to do.” The Army general was astonished at the answer, “What good would that do? He wouldn’t obey the orders”.10

The hesitancy of the Joint Chiefs was unfortunate because after Inchon, MacArthur’s concept of the war began to diverge more and more sharply from policymakers in Washington. After Chinese armies plunged into Korea with disastrous consequences for UN forces, MacArthur gave a published interview in which he said that the restrictions placed on him by the Truman Administration were “an enormous handicap, without precedent in military history”.11 Several months later, when the war had improved for the UN forces, the Truman Administration wanted to begin armistice talks with China. MacArthur sabotaged this initiative by sending a letter to a Republican congressman in which he asserted that “There is no substitute for victory”. The congressman then proceeded to read MacArthur’s letter on the floor of the House and within a week, MacArthur was relieved of his command by an infuriated Truman.

There are several governance lessons on full display in MacArthur’s case. One of Truman’s greatest strengths was the unanimity of his administration. Truman was an unpopular president but he enjoyed the support of his entire administration. He dismissed MacArthur after making sure that Secretary of State Dean Acheson, Secretary of Defense George Marshall and all of the Joint Chiefs of Staff supported his action. The value of developing a consensus among top decision-makers for a strategic plan cannot be overstated.

Another governance lesson exemplified by the MacArthur case is embodied in an Army general named Matthew Ridgway. In 1951, Ridgway was a two-star Army general and protégé of George Marshall who was well known and respected within the Army with a reputation for charismatic leadership in combat. His heroic performance in World War II had made him famous and well-respected with the American public. Ridgway was sent to Korea in December 1950 to replace one of MacArthur’s generals. Within three months, Ridgway had completely transformed the situation on the battlefield as he launched one offensive after another and regained much of the territory lost after the Chinese entered the war. One of the reasons why President Truman felt confident in his decision to relieve MacArthur was that General Ridgway was able to immediately step in and take MacArthur’s place. The governance lesson that Ridgway embodies is that the task of developing successive generations of strategic leaders is never a bad idea.

Conclusions

One aspect of the MacArthur example provides a valuable insight into crisis management. The lesson to be learned is- the leader that you have before a crisis might not be the leader that you want during a crisis. In June of 1950, the Truman Administration was caught utterly by surprise in Korea and, by reflex action, chose MacArthur as commander of the war effort. What the Truman Administration should have realized was that someone of MacArthur’s stature would be very hard to dismiss if he proved unacceptable. Truman, for example, could have kept MacArthur in Japan and sent a younger general to Korea. In 1950 (which was only five years after the end of World War II), if there was one thing that America had in great supply, it was combat-tested senior officers. The uproar that might have occurred if MacArthur were bypassed in 1950 was obviously nothing compared to the uproar that did occur in 1951 when he was relieved of his command in the middle of the war.

This article deals with political leaders who sought to manage generals who were popularly considered to be symbols of national resolve and the personification of victory. It is similar to the task that boards of directors face when trying to manage CEOs who have been deified by Wall Street. One insight from these cases is that symbolic leaders possess intangible resources that makes them highly resistant to bureaucratic authority. In Haig’s case, Prime Minister Lloyd George was forced to use indirect means to control his general because getting rid of Haig would have carried enormous and unpleasant political consequences. Firing Haig would have sent a message to the British people that the war effort was in deep trouble and this message would have disturbed allies and heartened adversaries. President Truman was able to pay the political price for dismissing MacArthur because, despite being an unpopular president, he had the unanimous support of his administration regarding MacArthur. Truman was also able to pay the political price of dismissal because MacArthur made the price lower than it might have otherwise been. After his dismissal, the MacArthur balloon lost air quickly. The year after his dismissal, MacArthur sought the Republican presidential nomination in the summer of 1952. At the Republican Convention in Chicago, Dwight Eisenhower received 845 votes on the first ballot while MacArthur received 4 votes. Eisenhower went on to become a two-term president and MacArthur, as he himself predicted, became an old soldier who just faded away.

Cover photo by Dave Lowe on Unsplash

Mike Hennelly

Mike Hennelly is a retired U.S. Army officer with a doctorate in strategic management. He has experienced leadership and strategy in the military world, the corporate world and the academic world. In his military career, he led soldiers, qualified as an Army Ranger and served as an Army strategist. He has worked directly with four-star generals and Fortune 500 CEOs. He has recently written “Athena’s Bridge: Essays on Strategy and Leadership.” The genesis of this book was the seven years he spent teaching strategy and leadership to cadets at West Point.

Footnotes

- Jan S. Breemer, 2010. “Defeating the U-Boat: Inventing Anti-Submarine Warfare,” Newport, RI: Naval War College Press. P.60.

- John Keegan, 1999. “The First World War,” New York: Alfred A. Knopf.P.299

- J.M. Winter. “Britain’s Lost Generation of the First World War” in Population Studies, Nov 1977. P.457

- David R. Woodward, “Britain in a Continental War: The Civil-Military Debate over the Strategic Direction of the Great War of 1914-18.” In Albion. (A Quarterly Journal) Spring 1980. P.46

- J.P. Harris, 2008. “Douglas Haig and the First World War,” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. P.543

- David R. Woodward, “Did Lloyd George Starve the British Army of Men Prior to the German Offensive of 21 March 1918? In The Historical Record, 27, 1 (1984). P.251

- J.P. Harris, 2008. “Douglas Haig and the First World War,” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. {.386

- Roland T. Berthoff. “Taft and MacArthur, 1900-1901, A Study in Civil-Military Relations.” World Politics, January 1953, vo.5, #2. P.206

- Forrest C. Pogue, 1987. “George C. Marshall: Statesman 1945-1959” New York, Viking. P.454

- D. Clayton James, 1985. “The Years of MacArthur, Volume III, Triumph and Disaster, 1945-1964.” Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. P.537

- D. Clayton James, 1985. “The Years of MacArthur, Volume III, Triumph and Disaster, 1945-1964.” Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.P.541