Let me paint a picture. You have just joined a team as a new manager and you have a member of staff who appears to be:

- hostile or has a confrontational attitude towards you, constantly criticising or belittling your leadership, or creating a negative workplace environment;

- reluctant to follow instructions, delays email responses, withholding key information, or consistently turning up late for meetings;

- using aggressive or manipulative tactics to get their way, such as subtle threats and/or intimidation.

Or you just have a strong feeling people are reacting to you differently, and you are becoming aware a staff member is spreading rumours or gossip about you and deliberately trying to damage your professional status in the eyes of others.

Do either of those scenarios seem familiar to you as a manager? If so, there is a strong possibility you have been Upward Bullied. This is when subordinates attempt to challenge a manager’s legitimate authority through coercive behaviour.

This insidious behaviour can be incredibly challenging for leaders and/or managers, who may feel like they are supposed to have all the answers and be in complete control. But fear not – you need not face this alone!

This series will explore: what we mean by Upward Bullying; why definitions matter; the risk factors for Workplace Bullying – particularly Upward Bullying; are current policies and processes effective; and next steps.

Introducing Upward Bullying

Most will be aware academics, government, and industry have long been interested in workplace bullying because of the short and long-term impacts on individuals and organisations. Firstly, at an individual level, there is increased absenteeism and related mental health issues.1’2 Secondly, there is an indirect financial cost at an organisational level, including reduced workplace productivity and performance through stress.3 Thirdly, a direct financial cost, with targets of workplace bullying more likely to leave an organisation rather than seek a resolution.4 And finally, it is an organisation’s ethical and moral responsibility to provide a workplace free from harm through intervention and action.5

Research into bullying began in 1969 and focused on incidents between pupils in schools, which included violent and non-violent acts such as social isolation.6 This remained the central area of focus until seminal work carried out by Leymann in the 1980s, who argued bullying could equally occur in the workplace with negative consequences. Leymann’s research was fundamental in beginning research into the detrimental effects of bullying on employees in the workplace, such as depression, feelings of helplessness and loss of productivity.7

Leymann used the term ‘mobbing’ to refer to the phenomenon. It was not until Andrea Adams and her Radio 4 series, An Abuse of Power, that the term workplace bullying entered the lexicon.8 Adams’ work focused predominantly on the misuse of legitimate power by managers or supervisors to bully subordinates.

However, research has identified three types of bullying in the workplace:

Vertical Downward Bullying

First is the most recognised and reported, Vertical Downward Bullying; when a manager or supervisor bullies a subordinate. In Downward Bullying we identify the manager as having legitimate power which they can misuse or abuse to undertake the bullying activity.9

Since the 1990s, research into workplace bullying has focused on these types of incidents. This was for good reason; you only need to look at the annual Civil Service People Survey (CSPS) statistics below on workplace bullying and harassment, noting it can take many forms ranging from denial of leave or unreasonable taskings to physical altercations.

Studies have found this to be the most prevalent, with 41% of Australian public sector workers10 and 58% of UK civil servants11 reporting a manager has bullied them in the previous 12 months. While a large body of research has focused on the public sector, it is worth noting the private sector has yet to be found to be immune.12

Horizontal Bullying

Secondly is Horizontal Bullying. This is more recognised in a school or training environment but is the second most reported type of bullying in the workplace – when a peer bullies a peer. Horizontal bullying or violence is defined as “hostile, aggressive, and harmful behavior … towards a coworker or group … via attitudes, actions, words, and/or other behaviors”.13 It is proposed that peer-on-peer bullying doesn’t occur based on the target per se, but rather on what the target represents to the bully, for example, when an individual feels threatened by a high-performing peer.

Vertical Upward Bullying

The least recognisable and least reported is Vertical Upward Bullying, when a subordinate bullies a manager or supervisor. Branch et al. identified, because of the lack of formal power, upward bullies are more likely to use covert methods such as rumour, gossip, and withdrawal of information to create the necessary power imbalance to undertake the bullying.14

Previous research has identified gender can play a factor. For example, some subordinates not recognising the legitimacy of the female boss.15 This finding was noted in the 2021 House of Commons Defence Committee (HCDC) report, where “overt hostility towards, and bullying of, women (often first into post)” was reported by interviewees.16

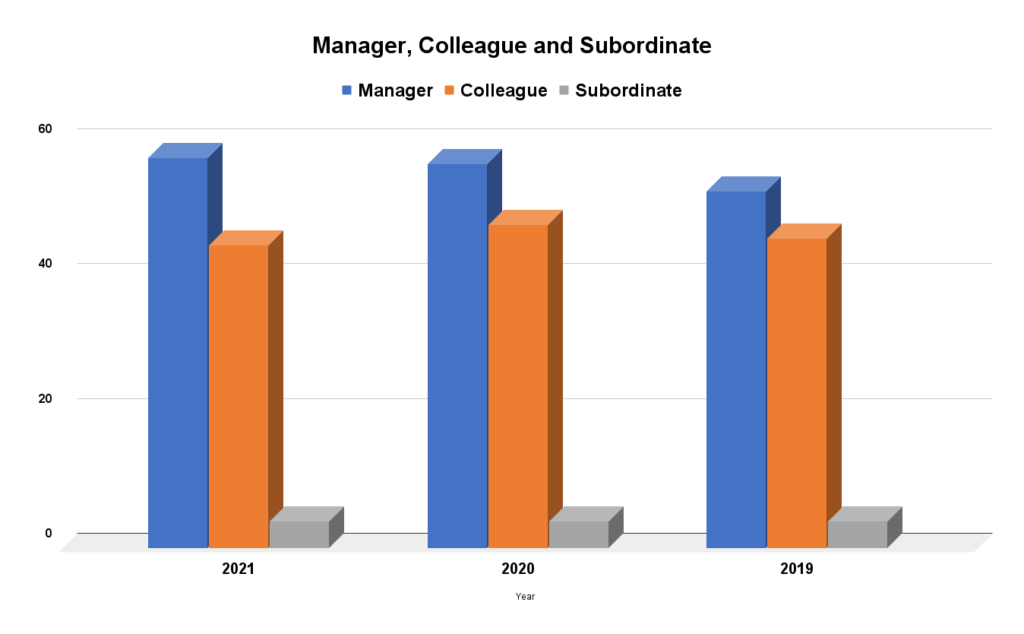

Zapf et al. reviewed the empirical evidence on the prevalence of workplace bullying and the perpetrators. They found “64.5% were bullied by supervisors, 39.4% were bullied by colleagues, and 9.7% were bullied by subordinates”, leading to the assumption “generally, superiors are seldom bullied by subordinates”.17

Since perpetrators of bullying are predominantly assumed to be in a position of power, there appears to be limited support or lack of understanding for managers when they are a target of upwards bullying. This can result in the “bullies receiving support from higher management” rather than the manager (target), and due to this lack of support, managers are more likely to leave the organisation than reach a resolution.18 Managers are also less likely to report the bullying as they do not want to be seen as a failure and feel it is a reflection on them. Research has also found perpetrators of Upward Bullying can and do use the internal grievance system to target their managers.

Conclusion

This short article aims to bring awareness to the phenomenon of Upward Bullying. It highlighted bullying, in any form, is not just a personal issue but an organisational one. Noting workplace bullying has both direct costs (replacing personnel) and indirect costs (lower morale, productivity, reputational damage, and decreased operational effectiveness).19

However, the costs of bullying go beyond financial considerations and can impact mental health, trust, and result in increased personnel disengagement. It has been proven at an individual level, it will impact “negatively on the psychology and physical well being of those who have experienced it”, resulting in absenteeism through stress.20 Therefore, it is an organisation’s ethical and moral responsibility to deal with the issue.

Leaders and managers are responsible for countering all forms of bullying and creating a culture of respect, inclusion, and accountability. It has been recognised managers are more likely to leave an organisation because of the current lack of recognition of Upward Bullying and limited support available to them. And sometimes, the current policy and processes protect the subordinate due to an inherent bias assuming the power lies in the legitimate hierarchical structure. An organisation can only support their managers if they acknowledge there are different types of bullying, including Upward Bullying. Thus, recognising the differences is the first step in ensuring the right policy and processes are in place to deal with it, no matter what form it takes.

Look out for Part 2 of the bullying series: Why definitions matter when discussing bullying.

Cover image by Road Ahead on Unsplash

Jane Doe

Nom de plume, Jane Doe has been in Defence for over 20 years working in HR and Change Management roles.

Footnotes

- Zapf, D., Knorz, C., & Kulla, M. (1996). On the relationship between mobbing factors, and job content, social work environment, and health outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 215-237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414856

- DfE. (2017). Preventing and tackling bullying: Advice for headteachers, staff and governing bodies.

- Robert, F. (2018). Impact of Workplace Bullying on Job Performance and Job Stress. Journal of Management Info, 5(3), 12-15. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511921018

- Bjorklund, C., Hellman, T., Jensen, I., Akerblom, C., & Bramberg, E. (2019). Workplace Bullying as Experienced by Managers and How They Cope: A Qualitative Study of Swedish Managers. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 16(23), 4693. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234693

- Rhodes, C., Pullen, A., Vickers, M. H., Clegg, S. R., & Pitsis, A. (2010). Violence and Workplace Bullying: What Are an Organization’s Ethical Responsibilities? Administrative Theory and Praxis, 32(1), 96-115.

- Smith, P., & Brain, P. (2000). Bullying in schools: Lessons from two decades of research. Aggressive Behaviour, 26, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(2000)26:13.0.CO;2-7

- Leymann, H. (1990). Mobbing and Psychological Terror at Workplaces. Violence and Victims, 5(119-126). http://www.mobbingportal.com/LeymannV&V1990(3).pdf

- Adams, A. (1992). Bullying at Work: How to confront and overcome it. Virago Press Ltd.

- Einarsen, S. H., Helge; Zapf, Dieter; Cooper, Cary. (2011). Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace. In Developments in Theory, Research and Practice (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

- Ayoko, O. B., Callan, V. J., & Hartel, C. J. (2003). Workplace Conflict Bullying, and Counterproductive Behaviours. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 11(4), 283-301.

- CabOff. (2022). Civil Service People Survey: 2021 results. Cabinet Office Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/civil-service-people-survey-2021-results

- Salin, D. (2001). Prevalence and Forms of Bullying among Business Professionals: A Comparison of Two Different Strategies for Measuring Bullying. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10(4), 425-441.

- Thobaben, M. (2007). Horizontal Workplace Violence. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 20(1), 5-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822307305723

- Branch, S., Barker, M., Sheehan, M. J., & Ramsay, S. (2004). Perceptions of Upwards Bullying: An Interview Study The Fourth International Conference on Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace, Bergen, Germany.

- Miller, L. (1997). Not Just Weapons of the Weak: Gender Harassment as a Form of Protest for Army Men. Social Psychology Quarterly, 0(1), 32-51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2787010

- HCDC. (2021). Protecting those who protect us: Women in the Armed Forces from Recruitment to Civilian Life. House of Commons: Parliament Retrieved from https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/6959/documents/72771/default/

- Zapf, D., Escartín, J., Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Vartia, M. (2010). Empirical Findings on Prevalence and Risk Groups of Bullying in the Workplace. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice, Second Edition. CRC Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1201/EBK1439804896

- Bjorklund, C., Hellman, T., Jensen, I., Akerblom, C., & Bramberg, E. (2019). Workplace Bullying as Experienced by Managers and How They Cope: A Qualitative Study of Swedish Managers. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 16(23), 4693. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234693

- Lewis, D., & Sheehan, M. j. (2003). Workplace bullying: theoretical and practical approaches to a management challenge. International Journal of Management and Decision Making, 4(January 2003).

- ibid