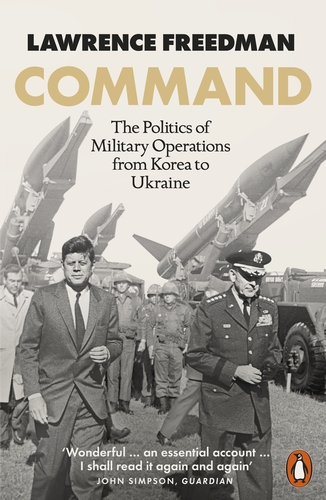

In, Command, Sir Lawrence Freedman, Emeritus Professor of War Studies at King’s College London, takes us through seven decades of conflict. Freedman analyses the complex command relationships between military advisors and political leaders. The book is readable and accessible with every chapter bringing a new, engaging story of ‘command’ throughout the decades; from MacArthur/Truman (Korean War) and Nixon/Kissinger (Vietnam) to Blair/Jackson (Kosovo) and Assad (Syrian civil war).

In short, this book is about power relationships and balancing the egos of generals and politicians! Whilst almost all the examples of military leadership are generals, there are leadership lessons that are appropriate for all levels of command.

One premise is that military decision-making is inherently political. Hence, the best military advisors must strike the balance between understanding how Whitehall or Washington DC functions, without overstepping the line and becoming overtly political. The most successful military advisors are those who recognise this tension and can navigate the diplomatic tightrope between civilian policymakers and hawkish generals.

Commit and entrust

The word ‘command’ comes from the Latin mandare, which means to commit/entrust and from which we get the word ‘mandate’. Another premise is that this mandate to lead is reliant on two things: institutions and people. When it comes to institutions, some leaders choose to seize control of institutions through undemocratic means. This eliminates the ‘inconvenience’ of parliaments and congresses slowing down a leader’s decision-making process. Other democratic leaders accept and even welcome the necessity to negotiate and compromise, recognising that the temporary ‘entrustment’ of command has accountability to a nation state’s permanent institutions. Freedman demonstrates that autocratic leaders fatally undermine their command by making their subordinates fearful or by alienating them.

One common experience is that the breakdown in relationship between politicians and military commanders leads to disaster. Whether it was the toxic confidence of General MacArthur advancing UN troops far beyond his orders (causing China to join the conflict), or the feeling of political betrayal felt by French generals in Indochina and Algeria, the breakdown in communication fatally undermines the chain of command.

Recurring themes

Another recurring theme is the hesitant attitude of politicians without military experience towards the generals advising them, shown with Kennedy, Thatcher, and Obama. In these cases, the generals are often tempted to overstep the mark and impose their opinions on their commander-in-chief. However, this works both ways, as politicians with some military experience consider themselves sufficiently experienced to side-line their generals, such as Donald Rumsfeld (Iraq). The best relationships between politicians and military officials are those in which both have a respectful understanding of each other’s positions.

Freedman uses less well-known cases, such as the Israeli General Ariel Sharon and the Pakistani General Yahya Khan. General Sharon saw his loyalties to the state of Israel and to his soldiers as more important than his loyalties to his orders (which did not endear him to his commanders). In contrast, Yahya focused on securing his power by constantly manipulating the upper echelons of the Pakistani military, which led to utter disarray when it came to defending East Pakistan (modern-day Bangladesh). Freedman also sheds new light on well-known commanders, for example, describing a key moment in the Falklands War when the Chief of the Defence Staff, Admiral Sir Terence Lewin, gave Thatcher a doctrinal objective for the Royal Navy Task Force. This simple, yet highly effective decision, was promptly adopted by the war cabinet and provided the foundation for her military strategy.

Ultimately, the most important question of command is yet to play out on the battlefields in Ukraine. Putin is an autocrat who values personal loyalty and adopts the tactics of a school bully. Those generals who survived the first eighteen months of the war are in no hurry to offer robust, honest advice. Zelensky is democratically elected and has good relations with his generals. There is a coherent strategic narrative that Zelensky, a former actor, has a natural aptitude for broadcasting. Freedman suggests that a commander-in-chief should understand the implications of military decisions without becoming fixated in the tactical detail; and generals should understand the political implications of their advice without allowing the political power to corrupt them.

Should I read it?

Freedman is one of the great international relations academics of our time, yet he has made this book very accessible with the variety of examples and the narrative pace. Take it chapter by chapter and there will be at least one example of command that you have never come across before. A book about relationships and people, with timeless lessons on leadership, diplomacy and communication.

Charlie J

Charlie J is a serving British Army officer in the Corps of Royal Engineers. He is studying for his MSc in International Relations and Strategic Studies, including research on French strategy in Mali and nuclear deterrence.