10 years ago to the day (16 December 2008), the Royal Navy’s Ice Patrol Vessel HMS Endurance catastrophically flooded. Her main engine room filled to the deckhead within 30 minutes. Such was our remoteness our Mayday call went unanswered. The crew and I spent the next 24 hours fighting for our lives.

This article is one of a three part series focusing on leadership, culture and priorities. More detail is found at the end of this page.

December 2008 – The Endurance

HMS Endurance was the Royal Navy’s ice breaker. In 1992, the MV Polar Circle was bought, renamed and thus replaced the previous vessel of the same name. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s requirement to maintain a Royal Naval presence in the deep south remained. In addition, she was able to survey previously uncharted waters and with two helicopters embarked, support the British Antarctic Survey in the excellent work they do down there. For the first 15 years of her RN life she deployed to Antarctica for the austral summer, returning each winter to the UK.

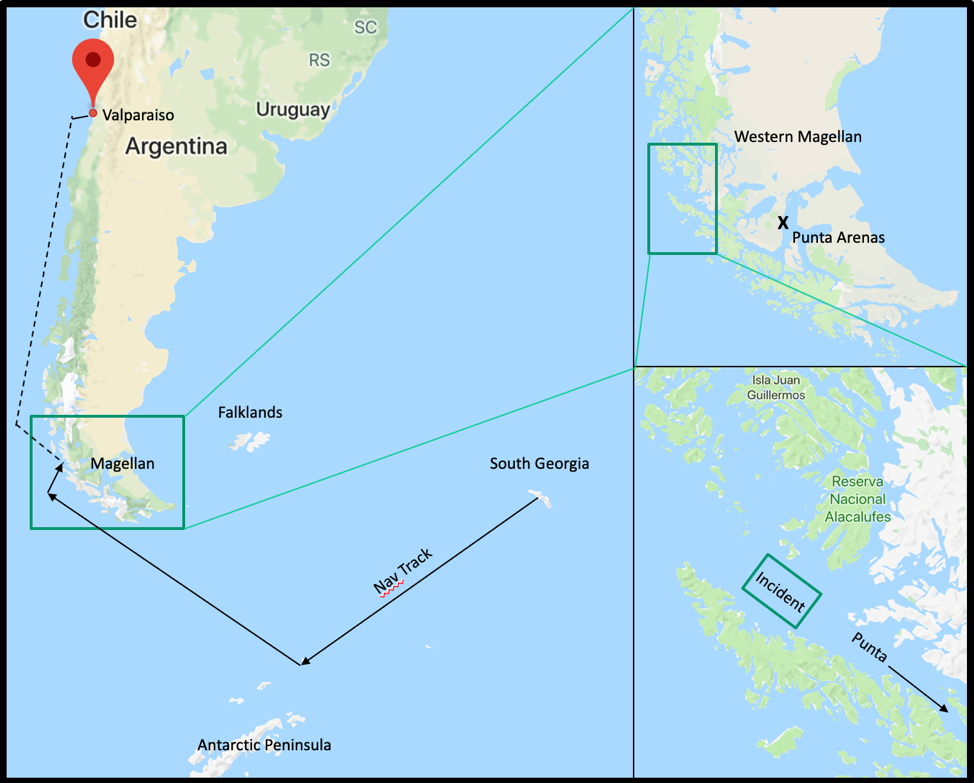

In 2007, this annual ritual was disrupted by an extended deployment; Endurance was tasked to spend the austral winter working off the coast of West Africa rather than returning to the UK. We completed operations off Antarctica as usual in April 2008, stopped for maintenance in Simons Town, spent the UK summer off West Africa as assigned, went back to the ice in Autumn 2008, and then spent a month off South Georgia before steaming for Valparaiso, Chile and a Christmas holiday for the crew in late 2008.

On 16 December 2008, HMS Endurance was in the western Magellan straits and had been operating both Lynx helicopters all day at the limit of their endurance and in foul weather. We were the Antarctic Patrol ship, so we were used to that. Having been on the bridge most of the day, approaching 4pm I used a gap in the flying to head down to my cabin for a leg stretch. Whilst there I heard the pipe “casualty in the engine room”. This is never a good thing. Before I had left my cabin to return to the bridge in response to the casualty pipe I heard, “flood in the engine room” over the main broadcast in a tone of voice that made my blood run cold.

The first 2 minutes – ‘we’re going to sink’

On arriving at the bridge, the first thing I noticed was the number of people staring at the engine room monitors. By the time I sat in my chair they were all staring at me. When I looked at the monitors, I could see a geyser-sized jet of water just off to the left and people rushing towards it with damage control equipment, a sight that will never leave me. The incident had been underway for less than two minutes and already the water was up to their knees. My first thought was “if we don’t stop that, this ship is going to sink”. My first statement, in the calmest voice I could muster, was “take the ship to emergency stations”. This triggered a number of pre-programmed responses, thankfully none of which included staring at me anymore.

It was clear that we were going to lose propulsion in short order. I knew from my years at sea what I should do with the few minutes of propulsion that I had left; head slowly into wind to buy more drift-time, but without increasing speed and thus the flooding rate. The 300m+ depth precluded anchoring and there were no beaches or shoal patches within the couple of minutes that I had available.

Reports from the scene of the incident were arriving thick and fast. What I wanted to know was ‘what caused it and can we stop it?’ Not far behind was, ‘what is the stability condition of the ship, where is the returning helicopter and who/how is the casualty?’

Minutes 2-10 – immediate actions

Endurance’s engine room was a sizeable compartment. At 1250 cubic metres it was roughly half the volume of an Olympic swimming pool. It was filled to the deckhead in 30 minutes. The sound of the water coming in drowned out the noise of both main engines. It’s hard to imagine what rushing into freezing water in darkened, moving, hazardous and deafening space would be like. I could see it happening and yet still can’t really imagine it. The ship’s company did unbelievably well, but it was hopeless. When the Chief Petty Officer in charge in there signaled it was time to leave, there were no dissenters.

The casualty had turned out to be the Chief Stoker, who would usually be responsible for leading our response to the incident. The flight deck Petty Officer who discovered the casualty took his headset off, made his way to the engine room and, without orders or formal training, stepped up into this most demanding role for the next 36 hours. The manner in which he performed it was as commendable as his decision to leave the upper deck and get stuck in.

Minutes 10-30 – loss of power

This was a key period in many ways. The damage control organisation was in full swing. The Engineer was communicating continuously between me and the Damage Control Officer, who had to sustain an extraordinary work-rate to keep on top of all the incidents and allocate personnel accordingly. Because the damage control effort is conducted from the bridge in Endurance and not separated from the command as it is in a ‘normal’ warship, I had to fight the urge to get involved and offer advice or, far more likely, interfere. This kept me free to look at ‘the bigger picture’ and actually it wasn’t that difficult – I trusted them.

Knowing that the rising seawater would damage or destroy the engines when it reached them and wanting to protect one engine so we would have power again when we stopped the flooding, the Engineer ordered the starboard main engine to be shut down. Keeping the port main engine running so that we could continue to head into wind for as long as possible definitely trumped safeguarding machinery. By the time the port engine arced dramatically to a halt and the prop stopped turning, the engine room was half full of water. About five minutes after this we lost all our electrical power when the auxiliary generators flooded as well. Our pumps stood no chance, and the compartment was evacuated.

The Leading Diver and his team made various attempts to re-enter the space with a view to stopping the ingress by manually closing the valve. Such was my keenness to try anything, his desire to get stuck in and the force with which this was being presented as a potential solution, I authorized the dives. They weren’t successful and it turns out that they couldn’t have been. I rightly (with hindsight) got a rap on the knuckles for endangering his life at the Board of Enquiry. However, the diver’s extraordinary efforts that day earned him a well-deserved place in an operational honours list.

This was also the time to ‘go external’. A phone call was made to the Fleet Operations Officer and the Fleet Emergency Response Cell (FERC) was activated back in Northwood Headquarters to provide a focal point for all communications. This construct was a direct lesson from a previous flooding incident and worked well. A mayday call was next – possibly a career low point. I’d answered and responded to dozens over the years and 90% were made by badly run yachts, and now it was my turn. Or more specifically my ops officer’s turn – I was still receiving critical information at a rate that precluded spending a couple of minutes on the radio. But then it got worse – no one answered. We really were on our own.

Loss of power was affecting us badly. The emergency generator in a commercial ship (which Endurance was built to be) is exactly that – it provides sufficient power and supplies to facilitate a safe evacuation and nothing close to the level of support that a comparable generator in a warship would provide. Communications were reduced to battery powered iridium phones and outgoing only. Our Global Maritime Distress System was without power as was our stability computer.

However, the loss of propulsion was worse. The ship, now stopped in the water, inevitably sat beam-on to the sea and was rolling about 30 degrees each way. It was hard to even hold on up on the bridge, let alone coordinate the damage control effort. The teams below had to contend with this whilst moving large, heavy items around. Worse, we discovered that our engine room was far from watertight. All the way around the deck above it were small, hidden holes designed to let condensation run into the engine space. No one either onboard or ashore that day knew of their existence. What we did know was that every time the ship rolled, water was forcing its way through these holes and appearing on the deck above. At one point we had nine separate floods to deal with along the length of the ship and no known cause.

By now, stability advice was coming in thick and fast from ashore which was needed as the computer that provided our stability data had lost power. Little of the advice was good news although it turned out that some of it was based on out of date information and the severity therefore exaggerated. When the engine room was a metre from being full and at maximum free-surface and the accommodation deck flood was a metre deep, the ship went rolled to 45 degrees and came perilously close to deck-edge immersion. Had that happened it’s very likely we would have capsized and someone else would be writing this blog. Fortunately, as the engine room filled to the deckhead, the water was unable to move about as much and our stability situation improved. However, there were now nine secondary floods around the ship, the ship was settling deeper in the water and our resources were being stretched thin.

At this point, the authorities ashore were urging me to abandon ship. There were a few reasons I didn’t do so despite the gloomy stability advice. First, it didn’t feel like we were going to capsize. Despite the exaggerated motion, years of operating in ships that deliberately stopped in deep water (not as common as you might think but mine warfare and fishery protection are two examples that I was involved in) made me think that there was nothing unusual about the motion – substantial, yes; unusual, no. Second, there was no easy way to get off. With no hydraulics to launch boats, an evacuation system that was limited to sea state 4 (we were at about a 7) and rubber life rafts with no engines (whose idea was that?), getting off would have been lethal. It seemed to me that for now, we were in the best life raft that we had.

All personnel had been accounted for, including our civilian passengers. As a research vessel, we often carried assorted civilian passengers, such as scientists, divers, camera crews etc. On this occasion we had a dozen or so 18-22 year old members of the British Schools Exploration Society who had just conducted the Shackleton walk across South Georgia as part of their leadership training. Fronting up to them after 20 minutes or so to explain what was happening was very awkward. Civilians do not go to sea in a Royal Navy ship to be told that it’s filling with water and that look was very clearly etched on many of their faces. My attempts to reassure them were partly compromised by having just climbed 10 or so ladders from the scene of the incident and so being out of breath. “Well they’re here to learn leadership” is the post-script to this scene that I don’t remember thinking at the time.

30 minutes to anchoring – rock and roll

The 30-minute point is a clear milestone in my mind as the full engine room gave the feeling that the water was no longer gushing into the ship which was a psychological relief. We were very far from being in the clear though. Some communications had been restored and we had a number of vessels closing our position. However, our drift course-and-speed had us on the rocks at approximately 0100 and only one of the closing vessels was going to make it in time. At some point we were asked by the FERC to pass the name of the island we were due to hit. Imagine our delight when we discovered it was called Desolation Island. From what we could see in the approaching gloom the waves smashing up the vertical rocks looked particularly rubbish.

We did have a small boat called MV Pudu closing us at his best speed of 5 knots. I had huge plans for him: take a line and pull our ship’s head into wind to stop the roll; be on standby to corral our life rafts should it come to it; generally save the day. What he actually did was close to about a mile, say something unintelligible, and then run for shelter.

However, with Pudu out of the equation, the need for a clear fo’c’sle had gone so I streamed the (marginally longer) starboard anchor to its fullest extent. I hoped that this would slow our drift rate but in any event, running aground in a poorly charted area with both anchors close home would be poor seamanship. It didn’t appreciably alter our drift rate; however, coincidentally or not, our angle of drift changed by about 10 degrees. This altered our time to running aground sufficiently to bring the cruise liner that was now steaming towards us into play and also meant that we were now heading towards the only shallow patch in the area. This was a rocky pinnacle 30m deep and we were cutting across the 80m contour. With the wind now at 50kts, this was not a sound anchorage but given the circumstances, it gave us some hope.

This was the moment to the address the ship’s company on the main broadcast for the first time. My Command Aim, from which the rest of the ship would derive their priorities, was ‘float’. that seemed to represent in one word what we were about. I was keen to ensure that no one got hurt taking unnecessary risks. Almost everyone dealing with the initial flood had been knocked off their feet at some stage. One sailor was caught by the wrist just before being swept over the side by waves breaking over the quarterdeck. Another got caught in a compartment with the water rising outside such that the door wouldn’t open. Her cries for help were heard about two minutes before we decided to seal off that entire section. Even the initial casualty was OK despite having been hit on the head by the valve lid as it blew off. After all this, I was keen that no one injured themselves now that the situation was stabilising. This was the thrust of my pipe – let’s do whatever we can to keep the ship afloat, but the moment for mad-bravery has passed. 30 seconds later we had a new casualty as they cut through a cable that was assumed to be dead without wearing the insulating gloves that were in a locker 20 yards away…

The FERC was also proving most useful as a funnel for our communications. I had a single point of contact to call at regular intervals as did the Operations Officer, both into the HQ at Northwood. The exception to this was the Engineer who had established a direct line to the architects, engineers and salvage teams in Abbey Wood near Bristol. The one unambiguous order I received during this phase was to get our civilian passengers off as soon as possible. Later, a Chilean helicopter with the ‘legs’ to do the return journey without refueling (our Lynx couldn’t) winched them off and that particular problem was resolved.

By now we had approximately 2,000 tons water in the ship and were both listing to port and sitting very low in the water (see before and after above, note the pennant number). Waves were breaking over the back of the ship and the hatch from the quarter deck into the aft hold was leaking badly. We were starting to lose the back of the ship. I didn’t need any external advice to tell me that if this hold flooded, we would lose the ship so I thought I’d head down there (or maybe the Executive Warrant Officer told me to, I forget) to see the issue for myself. It is ironic that my visit to see just how much trouble we were in was met positively by the group there who later told me that my arrival indicated that “we must be OK otherwise he’d be on the bridge”. With our fixed pumps unable to keep up, and our portable ones all lost in the engine room we had little option than to break out the silver rubbish cans, start up a chain and get bailing. In some of the smaller floods this proved quite effective whilst in other areas the endeavour was largely to keep people busy.

I also formed a small team to discuss the practicalities and mechanics of abandoning ship because if the anchor didn’t hold, that was the remaining option. The plan was to evacuate the ship but keep a team of about six back to take a line from the cruise liner if it got to us in time. We didn’t get as far as to how the stay-behind team would get off if it didn’t but fortunately it never came to that. During these discussions I forbad the use of the expression ‘abandon ship’ partly because like most sailors I’m superstitious, but mainly because it would be overheard, spread through the ship and affect morale.

Anecdotally, the Prime Minister, Gordon Brown was briefed during this phase along these lines:

“Prime Minister, we have a naval vessel in the Magellan Straits. She’s flooding and we may lose her”

“Is she going to run aground in Argentina?”…

“No Prime Minister.”

End of discussion. An interesting anecdote if true, not just because of his commendable geographic awareness but also the ability to immediately rule out any political risk and thus place the remaining issue in a box marked “Navy”.

At Anchor – we’re safe…ish

At about 0200, 10 hours into the incident, we were on top of the shallow patch. We were about two nautical miles from the nearest point of land – just over an hour to ‘abandon’ at our current rate of drift. I really didn’t expect the anchor to hold so that when the ship’s head appeared to be swinging into wind at first I wouldn’t believe it. Eventually, however, it became clear that the starboard anchor had the ship. I waited until the ship yawed to its fullest extent to port and then let the second anchor go, into about 120m of water. It took ten minutes of holding like this before I convinced myself that we were safely at anchor. I later discovered that the FERC had a most un-British eruption on hearing this news! In addition to being safe from the drift, the ship’s head was into wind and the crippling roll replaced by a much more manageable pitching motion. We could start to consolidate the shoring efforts below. Whilst far from being out of trouble, we were at last winning.

So now it was a waiting game. The bailing effort was broken into watches for sustainability and we prepared to be towed. The cruise liner was standing off a mile away to assist and the Chilean Navy were winching on additional pumps. Hot food and water was offered by the cruise liner which sparked an interesting debate ashore as to whether providing food in this manner constituted Assistance or Salvage. Contractually these are very different beasts particularly when a MoD vessel is involved. The answer was the former, but it was irrelevant when during the flying brief it became obvious that the cumulative risk of flying in this state and in these conditions was too high just for some food, so I cancelled the flying. The pilot quietly thanked me afterwards for that decision. The liner then declared their own medical emergency and asked for our doctor without which “the patient might die.” Good grief…back to flying stations.

We had about nine hours to hold out in this state until the salvage tug was due to arrive. The long night was spent shoring up the engine room bulkhead of which was bulging alarmingly, bailing, improvising food and hoping the anchors held.

Mr Charles Haddon Cave QC, in his razor summary of what caused Nimrod CV230 to crash (tragically killing all onboard) cited a failure of “leadership, culture and priorities”. His headings are the structure of this three part blog because they are relevant to this incident, if not necessarily as failings.

Part 1 – Leadership, narrates the incident as I saw it in temporary command of the ship, or at least as I remember it now 10 years on.

Part III – Culture, will look at what caused the flood. What was it about the ship that set it apart and yet rendered it so flawed? (due to be published Jan 19)

Commander Tom G Sharpe OBE RN (Retd)

Tom Sharpe is a freelance communications consultant specialising in managing reputations and capacity building for complex and often contested organisations. Prior to this he spent 27 years in the Royal Navy, 20 of which were at sea. He commanded four different warships; Northern Ireland, Fishery Protection, a Type 23 Frigate and the Ice Patrol Vessel, HMS Endurance.