I have a confession. I tweet. A lot. I tweet about dogs. I tweet about baking. I tweet about Defence. Worst of all, in some people’s eyes, I do it from a position of loose anonymity (BZ to @Average_Soldier for the turn of phrase). Some people know who I am, and I will disclose my name if necessary but I will not use my name as my Twitter handle.

There’s been a mass of Twitter conversations recently around people who tweet anonymously, and it has evoked some passionate debate across all points of the spectrum. Those who enjoy their anonymity talk about fear of reprisals, the ability for honest conversation and the freedom that tweeting without rank can bring. Those who oppose anonymous accounts see them as unprofessional at best and downright malicious at worst.

In some people’s eyes, my unwillingness to tweet under my own name makes me someone not worthy of engaging with. My unwillingness to tweet under my own name makes me a second-class Defence Tweeter, a troublemaker, a thespian or a troll. In reality, my relative anonymity is essential for my own piece of mind but the recent debates around the validity of engaging with anonymous Twitter accounts seems to be pushing me towards a cliff edge. Either, I start using my full name on Twitter or, I remain anonymous and see my engagements, my challenges and my discussions taken less seriously as a result. I assert that this is not only a harmful perspective for Defence to take but one that risks indirectly discriminating against women in Defence.

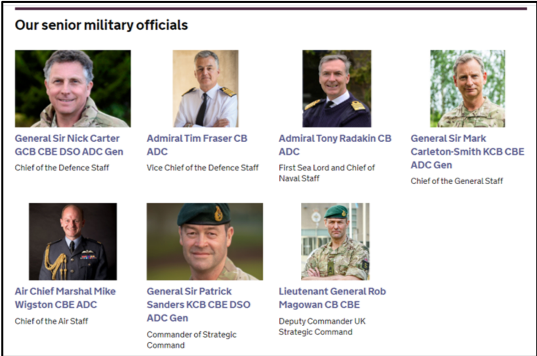

Women in Defence are still massively outnumbered by our male colleagues. As of October 2019, just 10.8% of the regular military, and 14.7% of the reserves was female. MOD Civilians fare only slightly better with 38% being female as of 31st March 2019 – the most recent figures available. Only 1 member of our Ministerial team is a woman and a glance at our GOV.UK page shows no female representation in our senior military officials. To put it simply, male voices dominate our discourse. When we do speak up, our viewpoints are considered by males, in male dominated environments and with a level of siloed thinking that bodes badly for our claims of being a Diverse and Inclusive Department.

Nick Pett, a senior MOD Civil Servant, recently wrote a Wavell Room article about the necessity of Feminism within Defence. Without getting into the rights and wrongs of this sort of article being written by a male, one paragraph stood out to me:

“One of the key things to accept, it seems to me, is that the prejudice, abuse, disadvantagement, mistreatment, violence, belittlement, diminishment that women experience is not an accident, it’s not natural, it’s not because of a few bad apples”

In short – the abuse that women face daily is endemic and that brings me back to Twitter.

In 2018, the Human Rights Councils Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences published a report focusing on online violence against women. Within the report, it states that:

“When women and girls do have access to and use the Internet, they face online forms and manifestations of violence that are part of the continuum multiple, recurring and interrelated forms of gender-based violence against women. Despite the benefits and empowering potential of the Internet and ICT, women and girls across the word have increasingly voiced their concern at harmful, sexist, misogynistic and violent content and behaviour online.”1

Before moving on to state that:

“Owing to the easy accessibility and dissemination of contents within in the digital world, the social, economic, cultural and political structures and related forms of gender discrimination and patriarchal patterns that result in gender-based violence offline are reproduced, and sometimes amplified and redefined, in ICT, while new forms of violence emerge. New forms of online violence are committed in a continuum and/or interaction”2

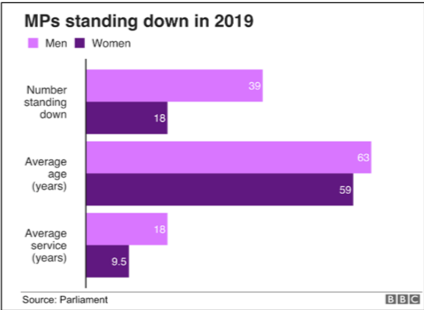

So, the everyday abuse and discrimination that women face, as touched on in Nick’s article, are amplified in a digital space. The amplification of abuse and discrimination in the digital world is well recognised. The build up to the 2019 General Election saw 18 female MPs choose not to stand for re-election with a number citing stating that threats, intimidation and abuse are part of the reason they were standing down.

On standing down after 22 years in Parliament, Dame Caroline Spelman stated, in an interview with the BBC that “Myself, my family and my staff have borne an enormous brunt of abuse and I think quite frankly we’ve had enough.” Analysis conducted after the campaign showed that candidates received an estimated four times the online abuse in 2019 than they did in 2017, with insults or abuse apparent in 16.5% of mentions or replies about them on Twitter. And the anonymity provided by social media allows online abuse to take a very different form to the usual name calling and bullying, especially when it is directed at women.

Amnesty International published a report titled “Toxic Twitter – A Toxic Place for Women” detailing, in depth, the sort of abuse that women face in the Twittersphere. It details name calling and body shaming, but it also details racism, sexism, homophobia and misogyny. It documents rape threats, death threats, targeted harassment against both the Tweeter and their families and doxing – all things that women are conditioned to be naturally fearful of, and with good reason given that:

- 20% of women in the UK have experienced some form of sexual assault since turning 16 3

- 29% of women in the UK have experienced some form of domestic abuse since turning 164

- 80% of all victims of stalking are women5

I turned to Twitter, at my brother’s suggestion, following a very nasty break up. For 6 years, I was involved in an abusive relationship, that saw me hospitalised on more than one occasion, stalked and worse. My world had become incredibly small and I was genuinely afraid of forming any sort of connection with people. Twitter, and the facility for anonymity, gave me a way of coming back into the world while protecting my identity in a way that meant he could not find me. It allowed me to reconnect with people in a meaningful way and went a long way to restoring my confidence. My anonymity was essential to that. Even now, a decade on, I maintain my anonymity on Twitter because, like virginity, once that anonymity is gone there is no way of getting it back.

When a man gets into an argument on Twitter, the worst that tends to happen is he gets called a few names. The game for women is entirely different. Putting our real names to our accounts opens us up to doxing, stalking, trolling, revenge porn and worse. The need for anonymity is again shown clearly in the Human Rights report – the highlighted sentence seems especially pertinent when we look at the Defence discussion around anonymous social media accounts:

“Another issue relating to the policies of intermediaries is anonymity and pseudonymity. While anonymity provides a veil for harassers and makes it harder to identify and take action against them, anonymity and pseudonymity are also crucial facets of privacy and freedom of expression for women. Women who have anonymous or pseudonymous online profiles are therefore also adversely affected by the policies on anonymity of certain intermediaries. From a gendered perspective, women should be able to use pseudonyms, which can help them to escape an abusive partner, stalkers, repeat harassers and accounts associated with the sharing of non-consensual pornography.”

And there it is in a nutshell. The ability for women to remain anonymous is a critical facet of protection for any woman who ventures into the world of social media. We may not all choose to use it but those of us who do, for whatever reason, should not be penalised for it.

Women’s voices aren’t loud enough as it is. Suggesting that we are only worthy of engagement if we tweet under our real names, risks pushing us back even further. If I must choose my safety over my voice, I will choose my safety and I won’t be alone. This risks pushing back the small gains that women have made in Defence. It means that online conversations will be for the privileged few who have reached a position where they are secure and comfortable in their ability to give their real names. Or, who are so disaffected with Defence that they will tweet any rubbish they choose and not care about the consequences.

The validity of my voice is no less important because it comes from behind an avatar. My arguments and ideas are no less worthy of consideration because I hide behind a nickname. Let us stop and consider someone who I admire greatly, the awesome Sir Humphrey otherwise known as @pinstripedline. Sir Humphrey is a loosely anonymous twitter account; however, he is still seen as one of the foremost Defence commentators in the UK. How has an anonymous account become seen as an expert? In terms of a policing intelligence assessment, he would be seen as a reliable source – competent and accurate with his information. Would this assessment be different if he suddenly changed his Twitter handle or used his own picture as an avatar? We should be looking at the quality of argument/debate/discussion that an individual provides rather than getting caught up in the name they use. Engage with the argument, not the individual.

My challenge to Defence comms is this: if we really want to be a diverse, inclusive and female-friendly organisation, lets come away from the outdated idea that only troublemakers choose to be anonymous and accept that for some of us, Personnel Security is far more than just a phrase, it’s embedded in everything we do.

@Madvixen1983

@Madvixen1983 is a MOD Civil Servant currently working in UK Strategic Command. Married to an RAF SNCO, she came into Defence following a successful decade managing territory sales for some of the UK’s biggest companies.

Footnotes

- Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences on online violence against women and girls from a human rights perspective, Page 5, Paragraph 14.

- Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences on online violence against women and girls from a human rights perspective, Page 6, Paragraph 20

- https://rapecrisis.org.uk/get-informed/about-sexual-violence/statistics-sexual-violence/

- https://www.womensaid.org.uk/information-support/what-is-domestic-abuse/how-common-is-domestic-abuse/

- https://www.womensaid.org.uk/information-support/what-is-domestic-abuse/stalking/