TL:DR

I have 2 propositions: firstly, the British Armed Forces’ understanding of leadership is seriously limited; and secondly, in light of restructuring following the Integrated Review, it is highly likely this limitation will result in catastrophic moral failure.

I argue that the qualities of individual leaders have, at best, a negligible impact in relation to the systems that they operate within. I will present various examples where military systems have gone badly wrong. Finally, I assess how the systemic conditions of the British Armed Forces are changing in a way that may create a ‘conducive environment’ for such pathologies.

Introduction

I recently attended an Army conference focussed on the topic of leadership. Much was as you may expect: we discussed the qualities we expect good leaders to embody; we learnt about upcoming mentoring schemes within Defence; and we were approvingly shown, absent context, anodyne quotes about leadership from men who could be called war criminals.1 I was not the only one to find this odd, and I have been tossing the matter over in my head ever since.

This article comes with many caveats. Although I am young, of junior rank and generally left-leaning, I have seen from conversations with colleagues that these and similar thoughts are also on the minds of my seniors (both in age and rank), seasoned veterans (particularly of Op HERRICK and Op TORAL, as one may expect) and those of a more conservative bent.

On the one hand, I am poorly placed to make serious change. On the other, I am part of the generation apparently so valued by the Army for its ‘self-belief’, the generation that barely remembers a pre-9/11 and pre-Afghanistan world and which will by demographic necessity be gradually filling positions of political and military influence over the coming decades.

This article, then, is an intentionally provocative starting point for further conversation, delivered in a spirit of critical friendship. My goal is to, as the Army Leadership Code states, ‘encourage thinking’. I am not so bold as to think I have all the answers, nor that I will be able to cover all the topics I wish to in sufficient depth in this article alone.

Welcome to the Machine

Much of the discussion around leadership, be it in military or business circles (and certainly at the aforementioned conference), tends to focus on the personal qualities of individual leaders. Good leaders should be ‘honest’, ‘accountable’, ‘brave’, and so on. They should act in service of others—their subordinates, their organisation, etc.—over their own interests.

These same characteristics find themselves presented in various combinations and under various pseudonyms in all manner of organisational value statements. It comes as no surprise that this is equally true of Britain’s Armed Forces: the Army (Courage, Discipline, Respect for Others, Integrity, Loyalty, Selfless Commitment), the RAF (Respect, Integrity, Service, Excellence) and the Navy (Commitment, Courage, Discipline, Respect for Others, Integrity, Loyalty) all have their own versions.

These are all noble values to foster, and military history provides many examples of the right person in the right place at the right time being the crucial difference between survival and disaster, from Soviet military officers Stanislav Petrov and Vasily Arkhipov to James Blunt in Kosovo. However, these are notable as exceptions to a much more common rule.

How many individually decent leaders have dutifully served appalling regimes? Erwin Rommel is a famous example; a man who was, by most accounts, a chivalrous leader and well-respected by his British enemies, yet his successes in Africa ultimately furthered the interests of the Third Reich.

On the flip side, systemic pressures may be too strong for even the most virtuous leader to overcome. Consider the reform-minded Joseph II, 18th-century Holy Roman Emperor, and in theory a man of absolute power, whose liberalising efforts were so roundly stymied by the entrenched interests of his time that his epitaph reads ‘here lies a ruler, who despite his best intentions, couldn’t realize any of his plans.’

The Pathetic Dot

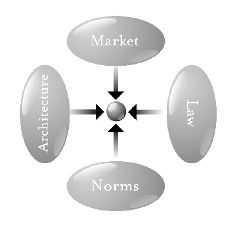

One way of considering this dynamic is through the pathetic dot theory, as advanced by Lawrence Lessig. This theory proposes that our actions are ultimately regulated by four forces: the law; social norms; the market; and architecture. By this model, the focus on individual leadership qualities and the constrained legal environment under which the Armed Forces generally operate represent a hyper-focus on the ‘social norms’ and ‘law’ forces, respectively, whilst the ‘market’ (in a broader sense than a merely monetary one) and ‘architecture’ forces are comparatively neglected.

If incentives are misaligned in such a way that cost-benefit calculations indicate that an illegal or immoral course of action may be the most profitable, the market force can act as a powerful driver against whatever laws and norms have been put in place. Similarly, if a situation is architected in such a way as to make following those laws or social norms difficult (or even impossible), their effectiveness will be constrained.

Its All About Your Base

Alternatively, there is a useful concept from Marxist theory (don’t panic) that can also help us to picture this dynamic: the base and the superstructure. The base represents the material conditions within which an individual operates. In the military context, this would be the ‘facts on the ground’, the realities of materiel and manpower, enemy activity, oversight, and the in-practice enforcement of discipline. The superstructure represents everything that is layered over the top of those conditions. In our context, this means values, ideology, policy, the in-theory enforcement of discipline, etc.

The theory proposes that each layer shapes and maintains the other, but that the base is ultimately dominant. The Armed Forces’ approach to leadership focuses overwhelmingly on the values and culture associated with the superstructure, yet the much more powerful force in determining outcomes is the oft-neglected base. Consider a group of sailors stranded in a lifeboat and without food; though they likely all hold the value that cannibalism is abhorrent, the material conditions of their tiny society likely mean it’s cabin boy fritters for tea.

The key point is that leadership does not occur within a vacuum; one is not simply ‘led’ in place, from nowhere to nowhere. The act of leadership presupposes a destination towards which one is being led. Each leader may well have their own idea of this destination, but ultimately each operates alongside countless others within a much larger system, with its own distinct goals and objectives. On this macro level, the qualities of each individual leader are at best negligible: ‘They’re all part of the same machine, and what comes out the end of the gears and levers is the same product, whatever their attitude is…the machine produces the effect it was designed for.’2

Runaway Trains

The direction that any system takes is the unconscious result of a complex set of feedback loops and incentives. Your respiratory system, for example, works by continually monitoring the levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide in your system and breathing in or out when they hit certain thresholds. However, systems are at risk of becoming self-reinforcingly pathological through the same mechanisms; in such a case, the incentives they present to their agents become perverse, and the results corrupt.

In this section, we will examine various examples of this happening within the military context, although similar examples can be found in fields ranging from healthcare to education. In the following section, it is important to bear in mind the phrase apocryphally attributed to Mark Twain: ‘History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes’. The future will not repeat the past verbatim, but it will echo it.

The most obvious and heavily analysed example of a pathological system is Nazi Germany. It is in her coverage of one of the post-war trials of a Nazi leader— that of Adolf Eichmann, a key figure in the organisation of the Holocaust —that Hannah Arendt proposed the concept of the ‘banality of evil’. In short, she argued that Eichmann and those like him were ultimately psychologically normal people who had become so focussed on the minutiae of their jobs (the timetabling of trains and so on) that they simply lost sight of the bigger picture of what they were doing.3

Arendt’s work remains influential, but hers and similar theories have been challenged by contemporary scholars, who argue that Eichmann and his ilk ‘did not simply follow orders’ but instead pioneered creative, new methods of deportation in part because ‘this won [them] the approbation and preferment of superiors’.4 That is to say, the incentives provided by the system encouraged them to exercise creativity, albeit in the service of evil. Some may have been true believers, others mere sadists or opportunists, but ultimately the machine produced the effect it was designed for.5

Let us turn to more contemporary examples. The ‘forever wars’ of the 21st century have offered copious evidence that our own military systems are not incorruptible. Pair two decades of demoralising counterinsurgency with a lack of effective oversight or threat of consequences and it becomes clear that beneath every ‘Kill Team’ or Haditha Massacre, every Abu Ghraib or Marine A, there could be a sizeable mound of atrocities that have simply yet to see the light of day.

In the United States, for example, investigative reporting has implicated SEAL Team Six in a veritable spree of war crimes. Similarly, in 2015, the Australian SAS was accused by the then-head of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation of fostering a culture of ‘arrogance, elitism and a sense of entitlement’, and five years later revelations of a similar nature led to the disbandment and re-naming of an entire squadron. One of the accused soldiers was Sgt Roberts-Smith, one of the four living recipients of the Australian Victoria Cross. It is worth noting that Australian media coverage has suggested an intriguing factor behind this corruption: influence from and envy of US Tier 1 Special Forces such as SEAL Team Six, who ‘got the sexy jobs [but] also drew fire [as] over time it became clear that maximum power with minimum oversight produces moral cost’.

If there are fewer examples featuring UK forces to reach for, it is not because they do not exist. Rather, the British Government has refused to comment on Special Forces operations as a matter of policy since the controversial killing of three unarmed IRA members in Gibraltar in 1988. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, however, and the occasional horror story still manages to filter through this wall of silence.

A 2019 investigation by BBC’s Panorama and the Sunday Times accused the MoD of covering up the killing of civilians by British forces in Afghanistan and Iraq. Vehement denials by the MoD were undermined when their own documents were recently released to the High Court. Similarly, justice for Agnes Wanjiru, allegedly murdered in 2012 by a British soldier, appears to have been similarly stonewalled, despite the accused having confessed to his comrades. The British approach appears to be ‘out of sight, out of mind’, but given our cultural similarities to, and close military links with our American and Australian counterparts, we should expect similar behaviours to those demonstrated by our better-documented fellow-forces.

Doing What They Can

This is not to say that the British Armed Forces make no attempt to mitigate the risks of moral injury inherent to military service. As per international law, the UK is ‘required to disseminate the texts of the Geneva Conventions 1949 and the two Additional Protocols 1977 as widely as possible in peace and war so that the general population can learn about them’, which it does through the requirement to complete Law of Armed Conflict training on an annual basis.6

Similarly, the Values and Standards of the British Army (and the equivalents within the other services) stress that ‘moral courage is the characteristic on which the other Values and Standards depend’, that ‘every soldier and officer must have the moral courage to challenge any behaviour which threatens our Values and Standards, irrespective of rank, environment or circumstance’ and that ‘being loyal to leaders or subordinates does not mean that wrong-doing should be condoned or covered up’.

The Defence Academy has supported the King’s College London’s (KCL) Centre for Military Ethics in putting together a set of free online courses, including one on the subject of ‘Armouring Against Atrocity’ that directly tackles some of the same issues raised in this article and should certainly be required viewing for anyone in a position of command. These are all superstructure-level (or norm- and law-level) interventions. It is telling that one of the deliverers of the course, Major Tom McDermott, in an earlier talk that pre-dates the Australian SAS revelations, cited the Australian VC recipient currently under investigation for war crimes as ‘a personification of that virtue ethic’ that he proposed as a tool to help promote correct conduct.

The Material Conditions of the Integrated Review

So, we have seen various examples of how the material conditions within which a military operates—its base, or architecture—can lead to a breakdown of command, discipline and even morality, regardless of the values it ostensibly holds, its superstructure, or norms. The question we must now ask ourselves is simple: what are the conditions under which the British Armed Forces will operate in the future?

The Integrated Review states that the UK ‘accept[s] the risk that comes with our commitment to global peace and stability, from our tripwire NATO presence in Estonia and Poland to on-the-ground support for UN peacekeeping and humanitarian relief’. It also pledges that ‘the UK will continue to play a leading international role in collective security, multilateral governance, tackling climate change and health risks, conflict resolution and poverty reduction.’ To do all this, we are told that the UK ‘will create Armed Forces that are both prepared for warfighting and more persistently engaged worldwide through forward deployment, training, capacity-building and education.’ As we leave Afghanistan with precious little to show for our twenty-year presence, the key takeaway appears to be ‘more, please!’. The Integrated Review promises a continuation of the post-9/11 state of constant militarism, poorly-defined boundaries and concurrent multi-national engagement.

The supporting Defence Command Paper reinforces this approach. It states that ‘the Army will be designed to operate globally on a persistent basis’. This includes the creation of an ‘Army Special Operations Brigade’ and ‘Ranger Regiment’, ‘able to operate in complex, high-threat environments, taking on some tasks traditionally done by Special Forces’—that is, taking on a role akin to the United States’ Tier 2 Special Forces, and freeing up the likes of the SAS and SBS to dedicate themselves to their Tier 1 role. Details of the new Regiment are still hazy, and the recently-published Future Soldier Guide has provided no further details, but it seems reasonable to expect that the same policy of silence that the UK Government adheres to elsewhere will also apply to the Rangers.

Building a Foundation for Moral Failure

The Integrated Review will oversee much smaller, more technologically-focussed British Armed Forces. What is more concerning is everything else it presages. We appear to be pivoting towards a far more secretive and less accountable force, partially privatised and openly inspired by the same US forces responsible for the crimes mentioned previously.7

They will continue to operate incessantly around the globe, in ‘discreet partnership’ with a rogue’s gallery of our least savoury allies, in the same conditions of ill-defined rules of engagement and the blurring of lines between civilians and combatants that have characterised the last twenty years’ worth of conflict. There are recurrent echoes in both documents of Dick Cheney’s 2001 suggestion that ‘we…have to work…the dark side, if you will. We’ve got to spend time in the shadows [and] a lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion…if we’re going to be successful’ —a position statement that preceded two decades of misery for those on the receiving end, from those tortured in CIA black sites to those still mourning their lost loved ones today.

Emphasising training and values are, ultimately, a weak from of deterrence; Marine A was not unaware that what he was doing was wrong, helpfully stating to camera that ‘I just broke the Geneva Convention’ after executing a wounded insurgent. I therefore propose that the British Armed Forces are overly focussed on the superstructure of its professed values and the qualities of its individual leaders. As a result, they have failed to notice that the base they are building is (to borrow a term from the recently-updated Army Leadership Doctrine) a perfect ‘conducive environment’ for moral failure.

Ben

Reservist for just shy of a decade, mostly in and around the Army Medical Services (AMS). International humanitarian law geek. Writing in a personal capacity; all opinions are my own and do not reflect those of my employers, colleagues or any affiliated groups.

Footnotes

- In ascending order of criminality: Colin Powell, who began his career aiding in the cover-up of the My Lai massacre and all-but-ended it lying to the UN to justify the invasion of Iraq. Stanley McChrystal, who oversaw the establishment of death squads during his troop surge in Iraq and Henry Kissinger, who by some assessments is one of the most evil human beings to have ever lived. At least Kissinger didn’t make it into the latest update of the Army Leadership Doctrine.

- R. Shea and R.A. Wilson, The Illuminatus! Trilogy, Raven Books, 1998, 184.

- H. Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Viking Press, 1963.

- S. Alexander Haslam and Stephen Reicher, ‘Beyond the Banality of Evil: Three Dynamics of an Interactionist Social Psychology of Tyranny,’ Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 33, Issue 5 (2007): 615-622.

- In a striking example, Karl-Otto Koch, commandant of the Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen concentration camps, was in fact arrested and executed by the SS for murder and embezzlement; see Konrad Morgen: Conscience of Nazi Judge.

- JSP 383, Manual of the Law of Armed Conflict, Ch 16, Part B

- For more on the detrimental ‘warrior ethos’ often espoused by these forces, see The Toxicity of the Warrior Ethos and Warrior is a Terrible Media Trope