BLUF: ‘Transitional Justice” is an umbrella term that includes processes and ideas relating to societies that are trying to transition away from conflict. It should be included in the UK MOD’s human security policy, conceptualised as human security cross cutting topic.

The UK MOD’s 15 December 2021 Joint Service Publication (JSP) 985 on human security missed the opportunity to incorporate Transitional Justice into its approach to human security. This article argues that the second volume of JSP 985, due to be released in 2022, should recognise the role of Transitional Justice in human security. Its incorporation would facilitate greater situational understanding, contribute to indicators for success of operations and help achieve lasting peace and stability. Policy writers should also establish a working group to implement Transitional Justice as a cross cutting topic in future UK human security policy.

This article begins with an overview of JSP 985. It then defines Transitional Justice and considers why it must be included in human security. Examples of UK MOD support to current transitional societies around the world are used as case studies to illustrate how it can improve the lives of civilians. Finally, recommendations are made for UK human security policy writers.

JSP 985 and Transitional Justice

On 15 December 2021 the UK MOD published JSP 985, Human Security in Defence. The policy does not explicitly mention Transitional Justice (TJ). Despite this, the policy is full of TJ sentiment signalling that the UK believes in TJ’s principles. The foreword by the Vice Chief of the Defence Staff is an example of this. Admiral Sir Tim Fraser emphasises “sustainable development” and “human rights”, with a focus on “individuals, communities, nations and regions”, “improving the conditions for stability” and “increase[ing] the prospects for long term peace and stability”. Sir Tim’s words directly reinforce this article’s central thesis: Transitional Justice is an indispensable facet of human security. Now is the time to formally recognise it.

What is Transitional Justice?

TJ is an umbrella term that includes processes and ideas relating to societies that are trying to transition away from conflict. No single definition will capture all elements as TJ is by its nature flexible. Different traumas, conflicts, crimes and victims will demand different responses at both the individual and collective level.

Understanding, supporting and designing TJ mechanisms forces a diagnostic and rehabilitative approach to a problem. It requires knowledge of the culture and political dynamics that led to the instability, as well as the possible social, political and legal pathways envisaged to escape it.

Academics now consider the following cases as foundational examples of TJ in action:

- Germany’s Nuremberg trials

- South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- The Good Friday Agreement in Ireland

- International Criminal Tribunals for Rwanda and Yugoslavia

- The role of Liberian women during the 1989-2003 Liberian civil war

- Colombia’s (ongoing) peace agreement

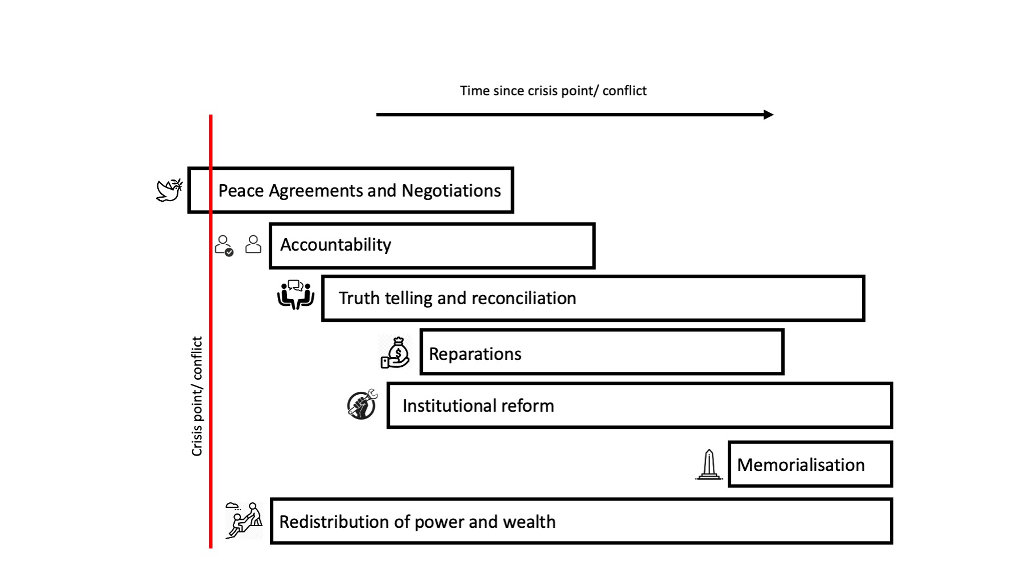

The Council of Europe states that “while there is no unique package of measures for dealing with, past or on-going, serious human rights violations, history shows that durable solutions cannot be achieved unless they are based on the pillars of justice, reparations, truth, and guarantees of non-recurrence”. Building on this, the Global Initiative for Justice, Truth and Reconciliation (GIJTR) defines TJ as consisting of five different components:

- Accountability

- Truth-telling and reconciliation

- Reparations

- Institutional reform

- Memorialisation

Many academics will argue that TJ components are broader than these five components. Expanding the definition of TJ, I believe two further components should be included:

- Peace agreements

- Redistribution of wealth and power

Peace agreements

Peace agreements, which set the conditions to design TJ mechanisms, almost always occur as bullets are still flying. Negotiations to reach agreements can be seen in modern conflicts in Ukraine and Yemen. Mali’s 2014 Algiers Accord, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s 1995 Dayton Accords, Nagorno-Karabakh’s 2020 Russia-backed peace deal and South Sudan’s 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict (R-ARCSS) were all agreed as causalities increased. Today all of these peace agreements are under heavy strain, in large part because TJ components were either unsatisfactorily constructed or unsuccessfully implemented.

Reparations and redistribution of power and wealth

Distinguished from the reparations component – the payment or other assistance made to those who have been wronged – the equitable redistribution of wealth and power must be considered in the TJ process. Inequality must be reduced and citizens should feel they have a meaningful stake in society. This creates a less divided society with less motivation for violence. Promises made to institute redistributive policies can be insincere, however. This is often observable in the post-Soviet space. In January 2022, President of Kazakhstan Kassym-Jomart Tokayev inadvertently claimed to be creating the conditions for wealth redistribution, though he was likely motivated by self-preservation in his efforts to placate the civilian population. Elsewhere, a hollow offer to ‘share’ power was made by later deposed Sri Lankan President Rajapaksa in early April.

Regardless of these leaders’ true interests, both are political offers signalling a potential transition to a fairer and more equal society, indicating a recognition of this component’s both real and perceived importance. Similarly, any TJ vision of a post-Putin and post-oligarch Russia would also be dependent on meaningful redistribution of power and wealth.

Accountability

Conflicts in the DRC, Sudan, CAR, Mali, Nigeria, Palestine, Myanmar, Afghanistan and Ukraine all have ongoing or preliminary ICC investigations. In 2011, as fighting raged in Libya, the machinery of justice also began to turn as the ICC opened a case against the then head of state, Muammar Gaddafi. This is important as it demonstrates accountability working in live conflict settings. Previously, TJ had traditionally been been conceived of as occurring within the post-conflict framework. This development marks a widening of TJ’s temporal conceptualisation.

Truth-telling and reconciliation

Whilst the ICC, and international criminal justice more broadly, play a role in accountability and reparations, they form only one part of TJ. International criminal trials have been described as “a necessary but not sufficient condition for transition”, with commentators recognising international criminal justice’s shortcomings in fields of reconciliation and social reconstruction. Truth-telling and reconciliation seeks the promotion of individual and collective healing. Examples of truth telling and reconciliation include South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and Rwanda’s Gacaca courts, a non-legal community reconciliation court that fostered dialogue.

Institutional reform

In most cases, a proportionate removal of compromised and corrupt actors is necessary in order to enable other TJ mechanisms to attain legitimacy. Key institutions need to be strengthened, adequately funded and all sections of society should be represented. The peace agreement should introduce anti-corruption guidelines and independent committees to guarantee long-term public sector accountability.

Memorialisation

Many societies are currently having difficult conversations about how to reconcile and memorialise uncomfortable past events, such as those that followed the toppling of the Edward Colston statue in Bristol in 2020. TJ mechanisms must include plans on how to collectively remember the distressing histories of post-conflict nations. The stakes are high, since memorials can be manipulated or “hijacked” to manufacture new meanings to different audiences. Indeed, there are many instances of memorials having been toppled and destroyed in the post-Soviet world, which have gone on to provide a symbol of resistance against the oppression represented by the original memorials.

Why Transitional Justice should be formally included in the human security landscape

Conflicts are not ended through victory but through negotiations. Successfully resolving conflicts requires parties to navigate tricky paths and consider clashing political priorities in their efforts to design TJ mechanisms that are appropriate to the particular context of the conflict.

However, not all negotiations yield a durable peace. If TJ practices are not adhered to, the following societal stresses can occur:

- perpetrators are not held to account

- truth is suppressed

- corruption continues

- power remains with the political elite

- justice is absent

- state institutions are underfunded and hollowed out

- elections are rigged

- narratives are manipulated

Many negotiations ultimately fail to bring about an end to a conflict. Nearly half of conflicts resolved through negotiations subsequently slip back into armed conflict. This is in large part because sufficiently strong TJ mechanisms were not constructed and society could not transition away from the existing conflict. For instance, in late August 2022, violence erupted once more in Baghdad: Iraq’s troubled power-sharing constitution and political dysfunction continues to erode the country’s ability to find durable peace and reconciliation.

Cross cutting topics

The existing human security Cross Cutting Topics (CCTs) are symptoms of instability in conflict and post-conflict settings. Often, the CCTs run the risk of being tackled in thematic silos, with each attracting a pool of resources allocated to address a specific objective. The current human security doctrinal approach of suppressing and extinguishing these symptoms should be expanded to include consideration of and engagement with TJ processes, conceptualised as a standalone CCT. The seven TJ components can be used as indicators and measures of success. Taking a more holistic approach to human security, and instituting TJ as an all-encompassing CCT, will both target the symptoms of instability and help to solve the underlying causes of the conflict.

International engagement activity must be underpinned by an understanding of the underlying historical, political, economic and socio-cultural dynamics of target regions. In addition to human security training, the “imperative for military personnel to be equipped with the technical, diplomatic and reconciliation skills and experience has never been higher”. The seven TJ components should constitute a bedrock of this training.

Front-line soldiers are already:

- working to hold war criminals to account

- documenting the truth

- working amongst communities

- reforming institutions at the sharp end

- preserving and recording history

They are already the best advocates to support TJ at the tactical level, but more needs to be done. Soldiers are increasingly acting out the roles of monitors, peacemakers and defenders of human rights. Including TJ in the human security framework will further equip and refine our soldier-diplomats with theory, understanding and strategic foresight. If we are serious about being global leaders in human security, TJ should be an indispensable facet in our approach.

Examples of UK MOD contribution to Transitional Justice today

Mali

Op Newcombe is the UK’s ongoing support to the UN’s mission in Mali, MINUSMA. MINUSMA is mandated to ensure the implementation of the Algiers Peace Accord – a 2015 internationally-brokered peace agreement – and to hold to account those responsible for crimes committed in Mali since 2012. The Malian signatories were under great pressure to accept the final text drawn up by France, Algeria, the EU and the US. Today, it has not received buy-in at the domestic level, in part because the historically aggrieved actors continue to feel excluded from the negotiating table. Since the outbreak of conflict in 2012, the situation in Mali has become more complicated due to the increased presence of organised crime, extremist Islamic militants and foreign actors. Climate change and the fight for resources act as conflict amplifiers in Mali and the wider Sahel.

British operations in Mali are conducted within the context of a ruling military junta that postpones elections, arrests civilian politicians and centralises their own power. The junta has encouraged secret local peace agreements, as seen in neighbouring Burkina Faso. Most institutions are subject to deep levels of corruption, and Russian Wagner operators – or “trainers” – are at the coalface of Mali’s military institutional ‘reform’.

On 1 September 2021, Op Newcombe Commander Will Meddings tweeted a thread detailing the Long Range Reconnaissance Group’s (LRRG) support to the United Nations’ Human Rights Investigation into a mass-killing near Gao. Meddings asserts that without the LRRG, the investigation team “would not have been able to stay on the scene or get the full picture of events”. The LRRG later visits the graves to count the dead.

This demonstrates the UK’s active use of TJ techniques in Mali. Collectively, MINUSMA works to help implement the peace agreement, including supporting political dialogue and reconciliation. Will Meddings demonstrates Op Newcombe’s on-the-ground commitment to documenting the truth. Evidence obtained will be used to ensure that criminals are held to account. Indeed, the ICC have already convicted Mali’s Ansar Dine Al Mahdi and are currently trying Al Hassan.

Understanding the current state of Mali’s TJ can help us identify the root cause of the conflict and its current trajectory, and better understand and execute our small role in its future.

Ukraine

Op Orbital is the UK’s training mission in Ukraine. The mission began in 2015 and has continued as Russian forces invaded the country in February 2022. The training represents institutional reform of the Ukrainian military, and has contributed to the defence of Ukraine over the months following on from the outbreak of war.

Neither Ukraine nor Russia have ratified the ICC’s Rome Statute (the treaty by which states submit themselves to the jurisdiction of the ICC). However, Ukraine accepted the jurisdiction of the ICC in 2015. An ICC investigation was fully opened following 42 state party referrals on 2 March 2022. Negotiations for a peace settlement continue to seem highly unlikely as the international legal community seeks innovative ways to hold President Putin to account for the illegal invasion.

The UK has taken a leading role in TJ in Ukraine, with a particular focus on truth-telling and accountability. On 29 April 2022 the then Foreign Secretary and current Prime Minister Liz Truss announced that the UK will deploy a team of war crimes experts to support Ukraine with investigations into Russian atrocities. This team will most likely have a military component supporting it. The team will gather evidence, particularly relating to conflict-related sexual violence. This evidence will be submitted to Ukrainian authorities for domestic war crimes trials or to international courts and tribunals, such as the ICC.

The UK’s leading role in the pursuit of justice, accountability and institutional reform in Ukraine is another example of the UK supporting TJ around the world.

The Balkans

The UK military has been engaged in the Balkans since the 1990s war responsible for the deaths of around 100,000 people. British forces are active through Op Elgin, the NATO Mission in Kosovo (KFOR) and regional exercises and training. British operations in the Balkans began as peace-enforcement and peace-keeping tools. Later deployments became tools of peace-building, the principal contribution being supporting the Dayton Peace Accords. British forces also took leading roles in activities including mass grave exhumations for accountability, truth telling and memorialisation purposes. In March 2022, the UK deployed a human security training team to Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) in preparation for a NATO assessment.

As a penholder during the writing of the Dayton Peace Accords, the agreement which ended the three years of conflict, the UK continues to have a responsibility for peace and security in BiH. British former High Representative Paddy Ashdown is memorialised in Sarajevo for his positive contribution to fostering peace and reconciliation between the three constitutive peoples (Bosniaks, Bosnian-Croats and Bosnian-Serbs).

Today, rising ethno-nationalism can be detected in most parts of the Balkan countries. Many believe peace is at risk in BiH, with some calling for reform to the Dayton Accords 27 years after they were first signed.

Long-term reconciliation continues to be damaged by:

- inflammatory and secessionist rhetoric

- denials of genocide

- resistance to war crimes investigations

- institutions that are weak and vulnerable to corruption

- controversial memorials.

Strong pillars of justice, reparations, truth and guarantees of non-recurrence are mostly absent in BiH. The prospect of EU membership had helped defuse some tensions but, as accession pathways have stalled, many in the Balkans are losing hope of progress, potentially posing another threat to reconciliation in the mid-term. It is a well-documented fact that a lack of engagement by the West in the late 2010s left a vacuum in the region, contested by malign international actors, particularly Russia. All of these factors have had an impact on the wider Balkan region’s continuing TJ.

The UK has responded to this situation with a suite of measures. In December 2021 Sir Stuart Peach was sent to the region as a special international envoy. In April 2022 the UK followed the US in sanctioning Bosnian Serb leaders Milorad Dodik and Zeljka Cvijanovic. It is not unreasonable to believe the UK could increase its military engagement in the region, following the example set by European Union Force’s (EUFOR) troop increase in March.

Furthermore, in June 2022 the UK deployed counter-disinformation experts and in July Deputy Ambassador Brown gave a speech to memorialise the victims of the Srebrenica genocide in BiH, proclaiming that “we will never allow such suffering in Europe again”. As calls for constitutional reform continue to grow, the UK as a Peace Implementation Council Steering Board member may have to participate in or advise on negotiations that will re-examine the Dayton Accords. These examples demonstrate the UK’s support to truth telling, memorialisation, negotiations, institutional reform and the redistribution of power – five key components of TJ.

As much of the region continues to torturously wrestle through TJ processes, a human security model with an understanding of TJ at its heart will create better structures for lasting peace in the Balkans.

Conclusion

The use of military hard power can provide an effective fix to crises, conflicts and instability in the short-term, but it has its shortcomings. Hard power does not address in any substantive way the root causes of the discontentment which shatters TJ mechanisms.

British operations demand a sophisticated understanding of the society’s culture, socio-political dynamics and identity, as well as its chosen (or imposed) TJ mechanisms, and the technical implications of all of these.

The Integrated Review (IR) recognises this demand and signals an intention to support “justice”, “conflict resolution”, “human rights”, the “rule of law”, “democracy” and “good governance” globally. Both the IR and JSP 985 clearly align with the goals of TJ. The IR’s language is more ambitious than JSP 985’s current understanding of human security – JSP 985’s forthcoming second volume needs to catch up.

The current human security doctrinal approach of suppressing and extinguishing symptoms of human insecurity should be expanded to include engagement with TJ processes, conceptualised as an all-encompassing human security cross cutting topic.

The seven TJ components can be used in human security mission planning as benchmarks to design strategic and operational outcomes. These components should then be used as key performance indicators, measuring the success of operations. Those designing or leading operations should constantly have these concepts in mind and underline their importance to all involved on the mission.

Recommendations

- A TJ working group or focal point should be established. The group should consider the merits of TJ conceptualised as a human security factor or a cross cutting theme in future iterations of UK MOD human security policy. Policy writers should consult with the working group on how TJ could be fitted into the existing framework.

- A Minister should be appointed to champion human security in Defence and across Government.

- Insights from experts in the FCDO, civil society and academia should be sought.

- TJ should be formally included into the Defence Academy human security Advisor’s Course syllabus as a permanent fixture.

- TJ’s inclusion into NATO CIMIC courses would present an opportunity to promote TJ at the alliance level.

- Defence should establish a TJ and human security career stream to grow skills over time.

- Pre-deployment training teams should give an overview of TJ in the region of deployment. This could be provided by J2 analysts, TAA analysts, cultural advisors, legal advisors and political narrative analysts.

- Defence Legal Services should be engaged to determine the boundaries of TJ’s reach into legal fields.

- A reflective study should be initiated. The study should reflect upon UK operations to date and determine examples in which the UK MOD has contributed to a society’s TJ. Lessons identified and best practice can then be shared in one document.