It was our own fault, and our very grave fault, and now we must turn it to use, We have forty million reasons for failure, but not a single excuse!” Rudyard Kipling

Context

This short story aims to bring tactical lessons from contemporary conflicts to life for junior commanders. Inspired by Captain (later Major General) Ernest Swinton’s classic work The Defence of Duffer’s Drift, it follows a young British officer and a small group of soldiers tasked with defending a key position, using a series of ‘dreams’ as a device to enable the defenders to iteratively improve their tactics.

While Swinton’s original was set during the Second Boer War (a “drift” being a vernacular term for a ford), this updated version shifts the setting to a near future war in the Baltics. Each failed attempt to defend the position, in this case a bridge, resets the scenario, giving the defenders another chance for success. The memories of the previous failures remain available to the protagonist, allowing a series of lessons to emerge through trial and error. This narrative device may feel familiar to modern audiences from the Duffers-inspired Tom Cruise film Edge of Tomorrow (or Live. Die. Repeat. for American viewers). No new resources are available at the commencement of each attempt. No new tech, no new kit, no external support. Much like the contemporary British Army, the defenders must adapt to fight tonight with what they have.

It must be stressed that this is not an ‘academic’ piece. It is intended to be a light, quick read for the junior commander. The lessons are also not intended to be definitive or prescriptive; rather, they represent a curated set of observations drawn from military, academic, and open-source material. Indeed, many of the basic lessons have not changed since Swinton’s original text and simply need to be re-learned.

The chosen dream sequence for this story focuses on the infantry platoon the bedrock of our warfighting capability, but the style could (and should) and should beused as a prism through which to teach and refine other capabilities. As the character of conflict continues to shift, in evolutions and revolutions, this specific story will also likely need to be augmented by new ‘dreams’ to address new tactical challenges.

How we defended the bridge over the Šventara By Lt Foresight Backthought, 5 LOAMS.

Prologue

Upon a still summer’s afternoon, after a long and bone-rattling journey across the flatness of the Baltics, we arrived at our objective: the bridge over the River Šventara. The long day of travelling, and the Vegetarian Mushroom Omelette ration pack that I had consumed, was likely responsible for the unsettled sleep and the resultant repetitive series of dreams I experienced that night. Each dream began the same, with our arrival that afternoon to that key bridge over the river, but each one played out differently. With each new dream I learnt new lessons and, somehow, I carried the lessons of each dream forward with me to the next.

The First Dream – relearning the basics

I felt a pang of dread and elation as the last of the column of vehicles rumbled across the bridge, down that straight tarmac road amongst the Baltic pines, and away into the distance towards the front line. This was the first time that I, Lt Backthought, had ever been alone in command of soldiers on a real operation. My platoon’s task was clear: as part of the Division’s Rear Area Security Group, we were to hold this bridge, some distance behind the FLOT and on a secondary route, to enable future operations. We would be here for 48hrs, after which time we would be relieved by follow-on forces. I had some thirty-odd soldiers with which to achieve the task, the rest of the company having now rumbled off to secure other bits of key terrain.

The rest of our division was committed away to the east, towards the border, where it remained engaged in efforts to break through the enemy’s frontage. It was doing its best to manoeuvre, to try and avert the war of position and attrition that the British Army so feared. We, however, were to remain static, defending this key terrain for the next couple of days. Although the front line was some distance away, we knew that groups of enemy advance forces were known to be operating throughout the area, looking to strike at our lines of communication and to seize key crossings for their next counter-attack.

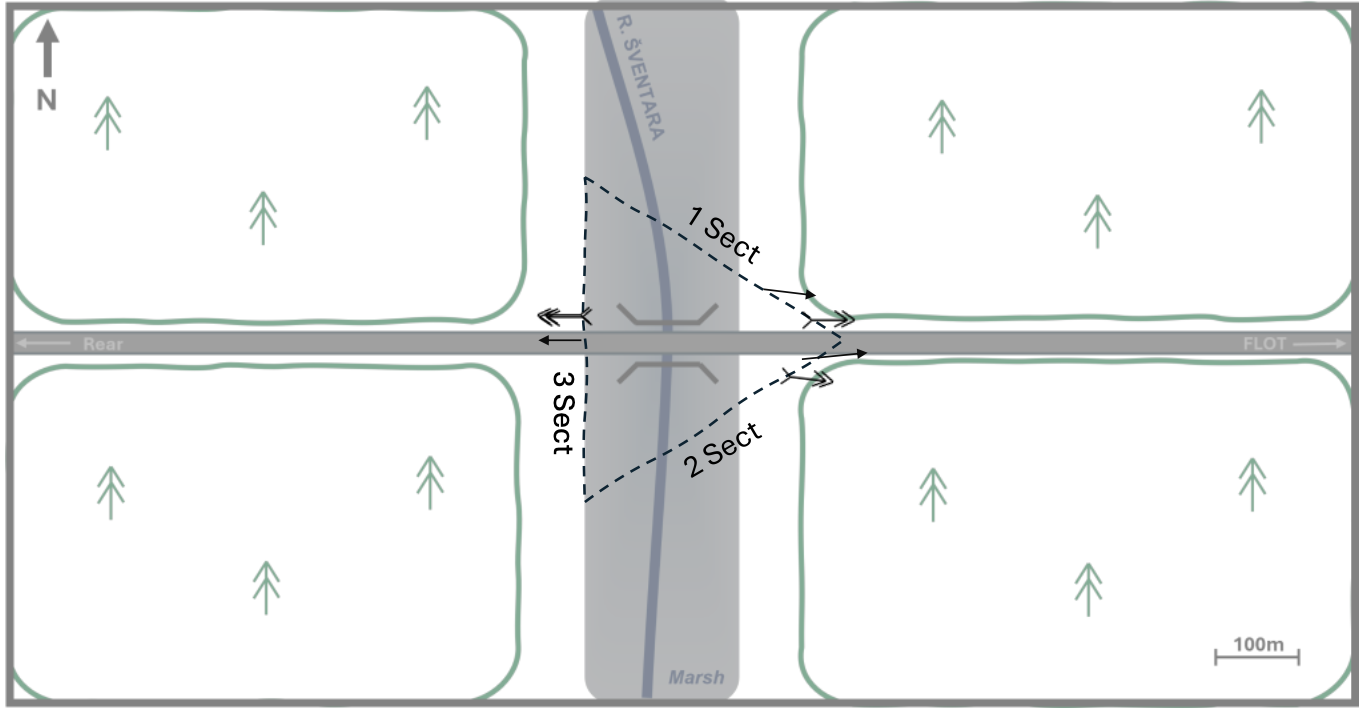

I surveyed my surroundings, and I began to create a sketch map of our area, which I have enclosed with this account to aid the reader. We had been dropped on the eastern side of the simple two-lane concrete bridge, a bridge that was the only crossing point over the river for many kilometres in either direction. The river itself, the Šventara, was a typical Baltic affair. It was some thirty meters wide, flowing slowly and steadily away northwards in the afternoon light of the summer sun. On either side of the river was a strip of boggy marsh that ran for a hundred or so meters, with the tarmacked road slightly raised to escape the sodden ground, after which the pines started again and marched off into the distance in every direction. From my map I could see that the nearest settlements were also many kilometres away. We were very much alone. My platoon were the typical reservist lot, ranging from the young to the old. Some had experience of campaigns in dusty places, but most had no experience at all. We had a pair of old Land Rovers, the now empty TCVs that dropped us having rolled away with the remainder of the company, but nothing heavier. Aside from our individual weapons we boasted only a smattering of GPMGs and a few NLAWs. We had our personal kit, replete with picks and shovels, respirators, some rather old HMNV sets, some cam nets with the vehicles, and a small scaling of BOWMAN manpacks. Aside from the addition of the NLAWs, kindly given to us by a regular battalion from the brigade, it was the same reserve infantry platoon that I deployed to Otterburn with on our last annual camp.

As I turned to survey my three sections, who were being marshalled into a neat little hollow square by the sergeant, I was overcome by a feeling of impending dread. I was plagued by a terrible vision of smashed trees, shattered bodies and angry shouts in a foreign language, and the exercise in writing letters to my soldiers’ families that I had undertaken at Sandhurst flashed across my mind. When I snapped back to the clearing in the pines, I saw that the sergeant was awaiting my orders. Thinking quickly, I told them to give the men half an hour to rest and eat in order to buy myself some time to think. As the hiss of Jet Boils and the fishy stench of hexi began to envelop the trees, I hastily began running through the seven questions in my mind.

I knew how to conduct a platoon attack, or a company attack at a push. I knew how to occupy a FOB of HESCO and sangars, and how to conduct a linear ambush against a rag-tag enemy. I even knew how to conduct an obstacle crossing as part of an armoured battlegroup, well, at least in theory. I could refight the Battle of Goose Green, Operation Panther’s Claw or the attack on PRACTAC hill, and I most certainly could write a well-referenced essay on the imperative for continuous professional development, but I had never been trained in ‘Rear Area Security’. However, the orders were simple: guard the crossing. We would therefore form an all-round defence. We would form a triangle of sections, centred on the bridge, as per the harbour area drills that we knew so well. One section would guard the home bank of the crossing, and two sections would guard the far bank. We would stash our vehicles off the road on the home bank, where I would also site my platoon headquarters. We were not due to be here long, so I told the section commanders to only have their men dig shell scrapes, much as they had been trained to at Brecon and Catterick, and to make sure that they built up some cover with sticks and foliage to disguise the positions. The GPMGs and NLAWs were to be placed so as to cover the road. I briefed the section commanders and, once they had finished eating, the platoon set about its business.

As we were finishing our rest, we noticed a small civilian pickup truck coming slowly along the road from the east. The occupants, a few older local men, stopped and struck up a conversation. They told us that they were fleeing from the fighting and asked us what we were doing here. We told them that we were here to protect the bridge, and kindly but firmly told them to be on their way. Whilst we were talking, one of the men in the back of the car seemed to be filming us on his phone. They thanked us, told us to be safe, and drove away westward.

Half an hour or so later, whilst the sections were just beginning their small scrapes, neatly spaced and in a linear fashion, the forest began to explode. Shell after shell, set to proximity, rained on our position for what seemed like an eternity, the whining of the incoming rounds drowned out by the earth-shattering airburst explosions that sent shrapnel and debris ripping through our positions. It was a blur from the start, and when I regained my focus, I found that I was lying on the floor, dazed and bloodied, with broken bodies all around me. The barrage had devastated us, with almost everyone now critically wounded. My wounds were as severe as my soldiers’, and there was no one to treat us. What had happened, I thought, as I laid back and stared up the sky. What had happened?

We hadn’t seen the enemy. We hadn’t even heard any drones. How had they acquired us so quickly, and so effectively? Then it dawned on me; the man in the car, the one with the phone, he must have shared our location, in detail, with the enemy.But how had their artillery fire been so quick, so accurate, and so devastating? They must have pre-sighted the bridge for fires, as key terrain, and we had done nothing to help by concentrating ourselves right on the position; we must have been an irresistible target. As I lay there, listening to the moans and groans, and waiting to slip away, several lessons formed in my mind as to how I would have done things differently next time.

- Every civilian with a phone is a sensor. Do not allow the local population to survey your dispositions.

- Do not site positions directly on vital ground or key terrain. A good enemy will also have identified it as such and will be prepared.

- Dispersal is critical for survival. Do not concentrate forces in the manner we have previously trained for: it is an inviting target.

- Do not delay digging in. Every second counts, you can rest when you’re safe.

I drifted away.

The second Dream – Drones

I came to with a start, the stench of hexi filling my nostrils. The sun was blazing bright again, and the rest of the company’s vehicles were rolling away eastward amongst the pines. The platoon was sat in a hollow square, the Jet Boils were hissing, and the sergeant was looking to me for direction. It was the same day as before, playing out again, but I could still remember the lessons seared into my mind from our previous effort.

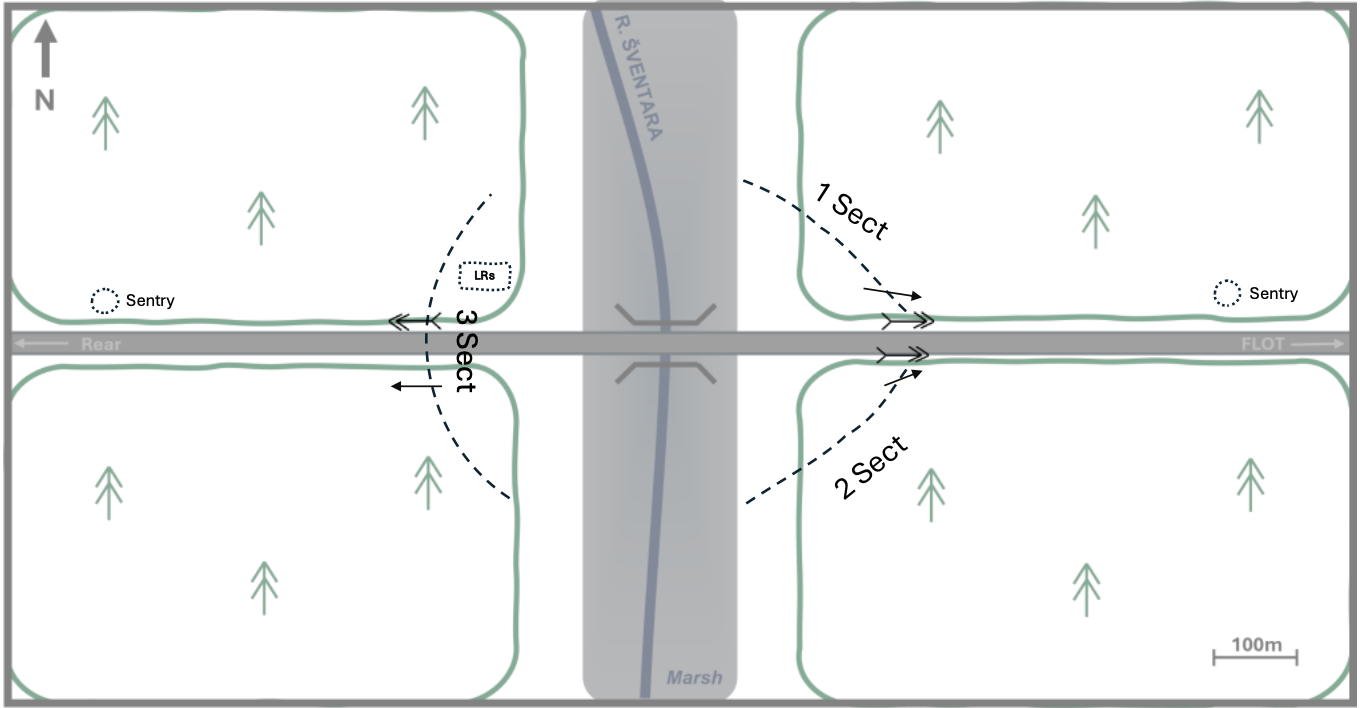

This time we would not dilly-dally. I told the section commanders that we would again form a rough triangle around the bridge, but this time we would push out much further, into the pines and with greater gaps between the scrapes. Eating would have to wait until the scrapes were dug. I also ordered the section commanders to place sentry positions further out along the road in each direction, with orders to turn around all civilian traffic. The Land Rovers were to be camouflaged amongst the pines to the west of the river, on the home bank, with cam nets put up straight away. The Jet Boil hissing stopped and, begrudgingly, the platoon set to work. After a while, the eastern sentry reported back that a civilian pickup truck had been stopped, had been turned around, and had driven away. The afternoon began to draw on, and the shadows lengthened, with the stillness of the summer’s day broken only by the dispersed sound of picks and shovels doing their business. My signaller and I sweated away as we dug our own trench just away from the Land Rovers. Sometime after the pickup had been turned away, one of the sections reported a buzzing noise overhead. Stepping out from my CP and pausing to listen, I could hear it as well. A low, very distant, almost inaudible buzz. We couldn’t see it, but it was there; we were being watched. The digging continued, with most of the sections now having created pretty decent scrapes.

Then the artillery started. It wasn’t the overwhelming volley of shells as it had been before, but single shells, at intervals, with bursts first around the bridge, and then moving out towards the section scrapes. First, the effect seemed minimal. Then, as the guns got their range, the casualties started. The half-dug shell scrapes gave some protection, but laid in the prone soldiers began to suffer from splinters from tree bursts, with injuries to limbs and backs, and two soldiers were killed outright.

The team medics rushed between scrapes to help the wounded, but this just seemed to intensify and sharpen the bombardment, so I ordered everyone to stay where they were. After a dozen or so shells, the bombardment ceased. All the while the buzz of the recce drone remained audible overhead.

Then more buzzing, louder than before. This time we could see it, flitting above the pines. A quadcopter, with a little package hanging underneath. It shimmied back and forth and then hovered directly over a shell scrape. As we began to fire at the drone, it dropped its package into the scrape. Before the occupants could clamber out the grenade detonated, to devastating effect in the enclosed space. A burst of GPMG fire brought the drone down. The radios were alive with traffic, with Coy Main asking us for a SITREP. They were unable to collect our casualties – which were now four dead and seven wounded, two of whom were severe – and directed us to bring them back to the exchange point a few kilometres to our west. I knew that movement would restart the shelling, but the severely wounded needed to be extracted now, and more droppers could reappear at any minute. I decided that we would evacuate them. The sergeant’s runner fired up one of the Land Rovers and drove it to the far side of the bridge to collect our wounded. As we began to haul the first of them into the back another buzzing noise rose from above the trees. Frozen, I watched in horror as a small racing drone, with some kind of large load underneath, shot towards us from just above the treeline. It exploded against the side of the Land Rover, scattering the wounded, new and old, me amongst them. As I lay there bleeding, facing up at the sky, with the bombardment having restarted with gusto, more dropper drones buzzing overhead, and the smells and sounds of carnage filling my senses, I wondered again what we had done wrong. Although it had taken longer than the first time, we had once again been rendered combat ineffective without even coming face to face with the enemy. We had dispersed, we had dug straight away, and we had shielded ourselves from the public.

How had they still found us so quickly? The civilians that we had turned around must have alerted the enemy to our presence. They wouldn’t have known our exact positions, but it was enough to arouse their suspicions and to cause them to recce our position with a drone. How had they done so much damage? Yes, we had dug straight away, but the shell scrapes offered limited protection from artillery bursts, and almost no protection against dropper drones. Finally, our obvious vehicle movement, whilst we were being observed, had drawn the FPV drone onto us. I’d put my soldiers in a position of helplessness, and they had simply died slower than the first time. Several new lessons formed in my mind.

- Concealment is the best form of protection. Do not announce your presence, even to local populations, unless you absolutely have to.

- Digging shell scrapes isn’t good enough. We have to go deeper. A simple Stage 1 scrape in the ground can quickly become a coffin. It provides limited cover from view and fire, is an easy target for a dropper drone, and is useful for only the most temporary of halts or when in contact. Digging Stage 2 slits should be the default minimum when going static.

- Cover from view is a 360-degree activity. Enemy recce will just as likely come from the air as the ground. All positions need some form of overhead camouflage.

- Air entries are a must. Personnel need to be dedicated to looking up aswell as out. These sentries also need to be equipped with something to defeat drones. In the absence of tech, a shotgun or machine gun will need to suffice.

- Do not try to move vehicles when you know you are being observed.

They are a clear target. Wait until times when they enemy’s sensors and effectors are degraded, such as night or when the weather closes in. If this isn’t possible, then move quickly, with sentries.

I drifted away.

The third dream – The electromagnetic spectrum and probing attacks

I came around with a start. The Jet Boils were being fired up, the sergeant was staring at me, and the dust was slowly resettling on the road as the rest of our company rolled away. I immediately began briefing.

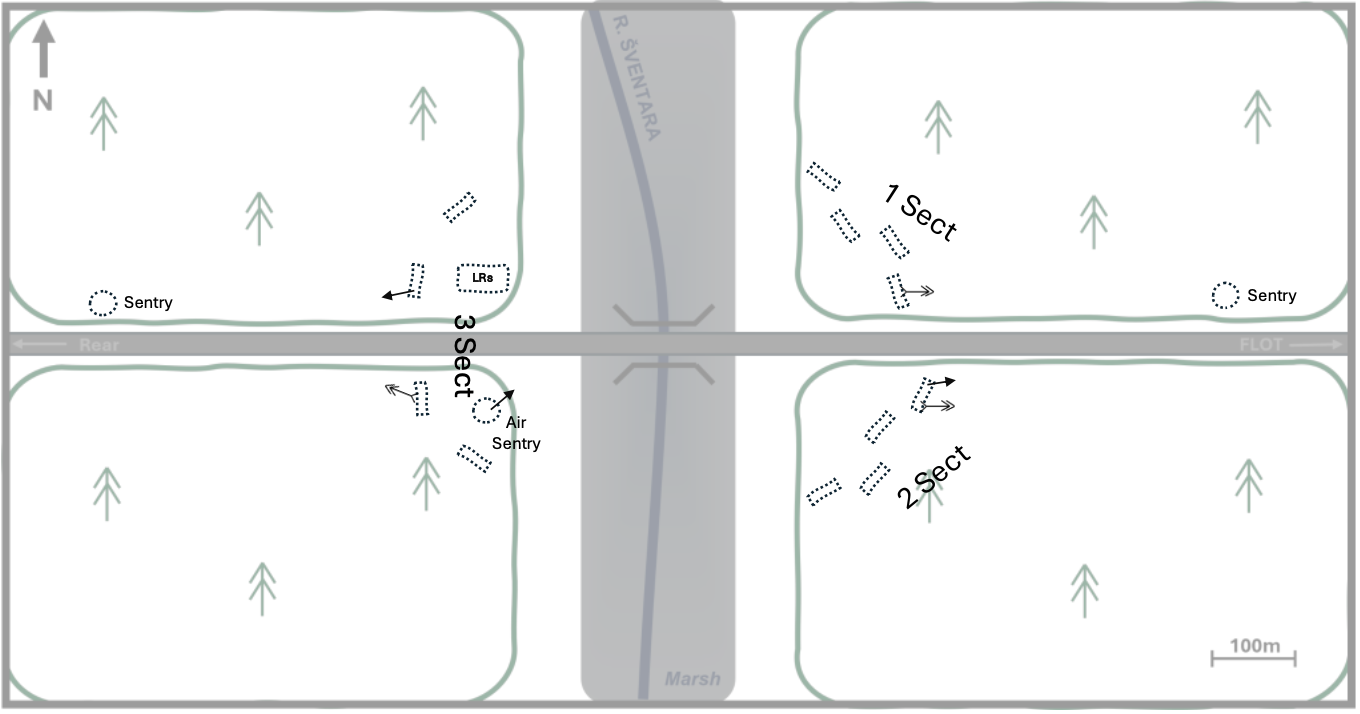

Again, we would form a dispersed triangle, but this time we would dig two-person slit trenches (this direction brought about some immediate grumbles). We would dig these trenches under the pines to provide maximum cover from the air (again, the prospect of digging amongst the roots brought more grumbles) and use ponchos, some of the cam nets from the vehicles, and foliage to enhance the overhead cover.

We would stagger the slits, in a crenellated fashion and not a straight line, to further increase dispersion. Once the slits were dug to a sufficient depth, future digging would be minimised to reduce the chance of our presence being detected. The road sentries were again pushed out, but this time they would be covert, ready to report back when they saw movement. An Air Sentry of two personnel with a GPMG was also initiated and set up near me on the edge of the treeline on the home bank.

The afternoon air was once again filled with the sounds of picks and shovels, this time interspersed with thwacks and curses as roots were struck. After a while, the sentries reported back that a civilian pickup was approaching. This was the signal for work to stop, and for the platoon to take cover. The pickup, unaware of our position, trundled through our frontage, across the bridge, and away to the west. We recommenced our digging.

The afternoon drew on, the light fading and the pines casting their long, final shadows over the bridge. Most of the slits had been dug to a good depth now, at least five feet in most cases, dirt giving way to wet clay, and each trench had some rudimentary overhead cover from view. The platoon began to settle in for the night. My signaller sent our daily SITREP back to Company Main, in a rather long-winded fashion, I must say. Realising that our comms were good, and that other stations were struggling to raise Zero, we also began to re-broadcast the SITREPS and messages for other force elements on high power; we were happy to add value.

Not long after the SITREP, that ominous buzzing sound from my previous dream restarted. I ordered all movement to cease. We waited, listening but unable to see anything above us in the greying sky. Was this a random patrol? Unlikely, I thought. We must have drawn the enemy’s attention in some way. After a while, the drone faded away.

Night drew in, and the clear Baltic sky was bright and full of stars. I set up a radio stag and then drifted to sleep in my slit, content with the progress that we had made. Just before midnight, the crack of rifles sounded from across the river, then silence. It was the sentry position on the eastern road. It had spotted a couple of dismounts creeping along the treeline and, after a challenge, had opened fire. The enemy had fled, and the sentries had drawn back into the main harbour area. It felt like the classic probing attack that we had been taught about. The night seemed to last forever. The sound of the river was the only constant in the background, and every groan of the pines or crack in the forest set the entire platoon on edge as we waited for further probing. Nobody slept.

At long last the grey tendrils of dawn began, individual trees reforming from the walls of pines, and the stars fading away. Then, more cracks sounded, much closer this time, followed by a long burst of GPMG fire. It was the western section being contacted, only a hundred meters or so from my position. They reported back the same; two enemy dismounts had approached along the road. One was dead, and the other had fled. We had been probed from both sides of the bridge, and it was now clear that enemy attack could come from any direction. We radioed the contact report to zero.

Shortly after the light had fully begun to break my signaller told me that, having spent the night acting as a rebro on high power, we needed to run a Land Rover to re-charge some of the BOWMAN batteries. I told them to crack on; the more value we could add for our flanking formations, the better. Within thirty minutes of running the Land Rover, the stuttering sound of the idling engine audible around the harbour, a louder buzzing noise started from over the trees, and, from my previous dream, I knew what would come next. An FPV drone slammed into the side of the Land Rover, mangling the vehicle and my signaller in the process.

More rifle fire followed, this time from amongst the pines, and on both sides of the river. Sporadic shelling then started, the probing parties seemingly directing fire onto the perimeter trenches. The morning dragged on, turning into a repetitive bout of enemy probe, followed by a few shells, and then a lull. We killed several of the enemy scouts, and only sustained a few minor casualties to shrapnel, safe in our slits, but they had obviously now established a good idea of our positions. Mid-morning brought more drones. A dropper-drone was sighted, flitting along the treeline – it seemed to be struggling to identify targets. It tried to drop its load on a trench, but the grenade got caught in the foliage and cam nets, bounced off to one side, and only caused concussion and ear damage to the occupants. The Air Sentry then brought it down with a burst of GPMG fire.

By midday, halfway through our time on target, I was beginning to feel quite pleased with myself. Not only had we survived long enough this time to actually come face to face with the enemy, but we had actually seen them off, from multiple directions, with relatively limited casualties. My signaller had been killed, and our primary BOWMAN set and our means of recharging batteries had been destroyed, but aside from some superficial wounds the rest of the platoon remained intact. Managing to raise Zero on one of the section BOWMAN sets, we informed them that we were okay, for now at least.

Just as I was enjoying a cold sachet of sausage and beans, a rising buzzing noise started, louder than before. Then it became clear that it was multiple drones, streaming towards us down the road from the east. Three FPVs, fast and heavily laden, swooped down onto the trenches at the apex of the road. One was brought down with rifle fire, but the other two worked their way under the cam nets and branches and detonated directly in the eastern-most slits. Unable to escape in time, the helpless occupants were savaged by the blasts. I tried to raise Zero, but our comms had become unworkable.

A heavy bombardment started, one shell every ten seconds or so, ineffectual against the trenches but seriously wounding a section commander and a medic who had moved across the open ground to try help those in the smashed forward slits. The scream of mortar bombs now joined the swell of artillery, smoke interspersing the HE and filling the trees with an acrid cloud. The platoon cowered, waiting for the bombardment to stop. As we crouched, we became aware of another sound, less buzzing and more mechanical, approaching from along the eastern road. Peeking above the parapets drew potted rifle fire from amongst the trees, and risk from the shells, but amongst the smoke the unmistakable shapes of two BMP-3s, speeding down the eastern road towards us, cannons beginning to blaze.

With the forward slits obliterated by the FPVs, there were no NLAWs on that side of the river with which to engage the vehicles. The shelling had stopped, the blasts of the shells now replaced by the roar of the BMP engines, and the small arms fire on the perimeter, with enemy machine guns now joining the fight. I ordered the NLAW from the west bank to reinforce to the east, but in dashing across the exposed bridge the operator was cut down by small arms fire. We were caught between a rock and hard place. The BMPs, now through the eastern perimeter, stopped and began to hammer cannon fire into the nearest slits whilst dismounts burst from the rear to mop up.

They knew exactly where our positions were and methodically began to clear through them, now able to enfilade them from close range. Caught between the small arms fire from the perimeter and the cannon fire from within, we were helpless. I tried to raise Zero, again to no avail, and then ordered the platoon to surrender. But no quarter was given. This enemy force had no interest in taking prisoners, so far behind the FLOT, and each trench, with its shaken and surrendering soldiers, was the target of further grenades and rifle fire. I leapt out of my own slit, running across the bridge towards the BMPs and waving my white rifle cleaning cloth to show my intent, but I was hit by small arms fire and fell. As I laid there, bleeding, watching the enemy comb through our dead and beginning to consolidate on the position, I was angry. Yes, this time we had been given the chance to have a crack at the enemy, and had given their probing sections a bloody nose, but again a force no bigger than my own had totally destroyed us.

We had made progress, but we had also made more mistakes. Our incessant re-broadcasting, from one position, on a piece of key terrain, must have alerted the enemy to our position, drawing their recce onto us. Once we had been forced to unmask on the probing sections, they knew exactly where we were. Running the Land Rover, stupidly at the coldest part of the day, had drawn the enemy FPV drones to us, an easy target. Yes, the slit trenches and the overhead cover had protected us to some extent from the artillery and the dropper drones, but they were still vulnerable to FPV drones, and the second we had to leave the trenches to support or reinforce others we had been mown down in the open. The enemy recce had also identified all of our positions before their attack; we had not deceived them at all.

Again, a new series of lessons formed in my mind.

- Do not broadcast unless you have to. Unless there is a critical requirement to broadcast do not do so. The enemy’s EW sensors will acquire you and bring recce units to your door.

- If you have to broadcast, ensure that you do it from different locations. Repeated broadcasts from the same location will not just see the enemy acquire you, but will also make you a target for engagement. If you have to broadcast, ensure that you do it from different locations.

- The rear is porous, expect attack from any angle. All-round defence remains a must.

- Be aware of thermal signatures. If vehicles or generators have to be run, try to do so during the day, for the shortest time possible, and ideally behind some thermal cover.

- Individual trenches provide great cover from artillery but trap the occupants and restrict movement. Trenches, once dug, should then be connected to provide options for covered movement, and an escape from FPV drones.

- Tactical communications will inevitably fail in contact. The enemy has a greater jamming capability than we do and knows how to use it. Do not base your plans on an assumption of uninterrupted communications.

- Disperse key equipment. Concentrating signature equipment, in this case, NLAWs and GPMGs, risks losing them all at once. Disperse then be prepared to concentrate for effect when required.

- Dig dummy positions. For the sake of extra effort, dummy positions (trenches, cam nets etc.) can cause the enemy to waste precision munitions and drones.

I drifted away.

The fourth dream – Not being a passenger

I awoke with a start. The Jet Boils were being pulled from bergens, the sergeant was hauling his webbing on, and the remainder of the company was just starting to roll away into the distance. I paused, considering all of the lessons that I had learnt, and decided to make radical changes.

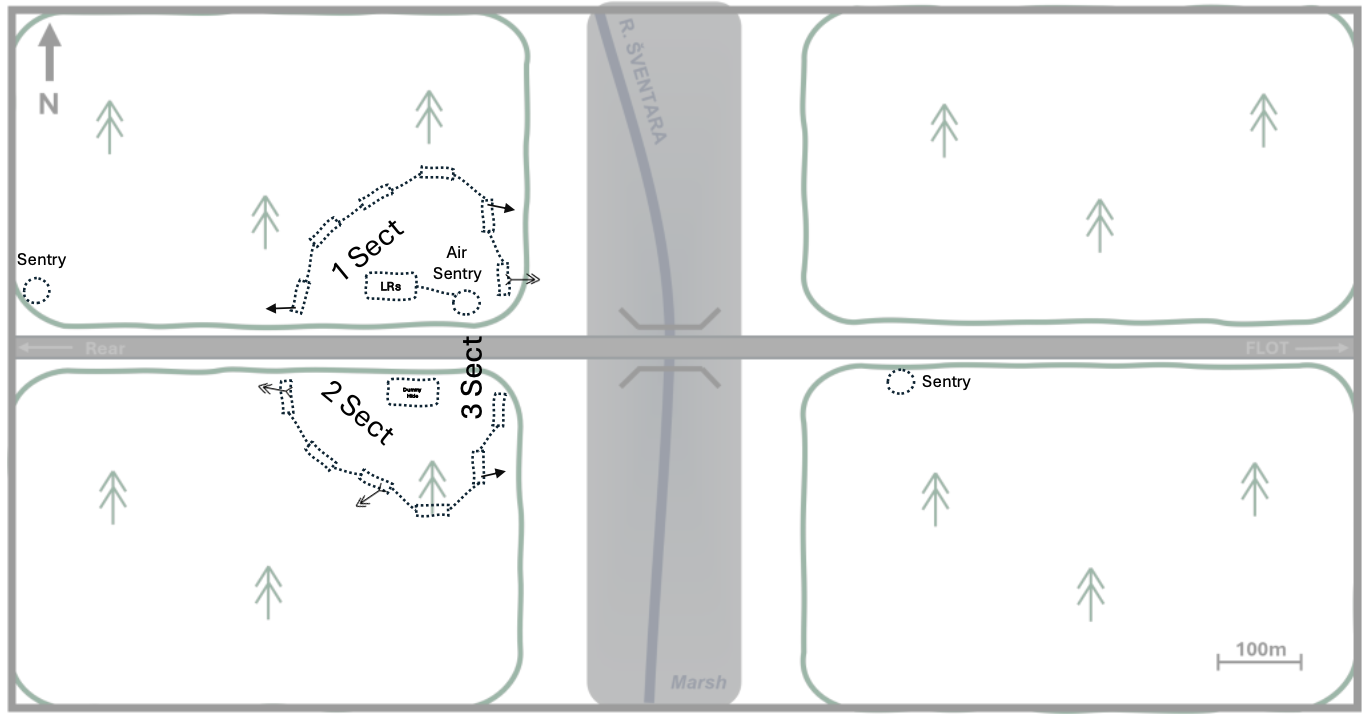

We would again form a triangle of all-round defence, but this time we would site ourselves entirely on the home bank, and a hundred and fifty or so meters from the bridge. One side of the triangle would face the bridge, along the line of where the marsh met the pines and with the road running through the centre, whilst the other two sections would tilt back through the forest to meet at the westward road. This would afford us far better arcs across the open marshy ground on either side of the bridge, preventing the enemy from encroaching unseen through the woods on this side, and would canalise any approach from the east across the bridge. It would keep us some away from the enemy’s likely pre-sighted fire zone and would mean that almost all movement within our position would be amongst the trees. The harbour would also be bigger than before, to allow for the dummy positions that I now planned. I pulled in the section commanders and my headquarters team and briefed them. Along with our new position and greater perimeter, I gave differing orders for our defences. Again, the troops were to immediately begin digging two-person slits but were to cease digging when they had got the trench deep enough to crouch in. Effort would then switch to digging shallow communications trenches, two or three feet deep to begin with, between each slit. The communications trenches would run at zig-zags, each zig or zag no more than six or seven feet long, to ensure that any blasts or enfilading rifle fire would be contained. Once a rudimentary perimeter of slits and connecting trenches had been established, which I roughly estimated would take us the best part of both today and the coming evening, we would begin creating dummy positions of brush and foliage in between each slit, whilst also continuing to excavate the existing trenches.

I also gave orders to push out two-person sentry positions along the road in each direction, as we had done before. We would also consistently deploy a fire team to conduct ground domination patrols around the harbour, with orders to push out several hundred meters into the pines. We would take the fight to the enemy and try to blind their inevitable probing attacks.

The first role of this patrol would be to escort my signaller a kilometre or so back down the road to the west. From here, away from our position, they would send a message to Zero, politely informing them that we would be henceforth adopting radio silence, only to be broken if we were under sustained and deliberate attack. For the first time, my section commanders baulked. With the sentries pushed out, and the constant patrolling, we would only have two sections of workforce with which to dig amongst the pines, with little time for rest. I explained to them my logic; we would get the initial trenches dug now to give us the vital protection that we needed, and then use the night, which gave us limited cover from the enemy recce drones, to expand the trenches. We would then rest the following day as much as possible, before continuing to expand the trenches the following night, to be relieved the following day. I also reinforced my newly held view that, regardless of how careful we were, some sensor, be that a civilian, a recce drone, a probing patrol or some direction-finding bit of EW, would eventually notice that we were here, so it was imperative that we prepared as quickly as we could. The idea of digging for two nights straight, only to then hand our hard dug defences over to the relieving troops, bugged my corporals, but having heard my logic they nodded assent.

So, works commenced. The sentries were set. The sergeant, his runner and I got our Land Rovers under the cover of the pines and set up the cam nets. We also used our spare cam nets to set up two more dummy vehicle hides on either side of the road. The patrolling fire team escorted the signaller to send their message announcing our move to radio silence, and then set off to patrol the pines, trying as best they could to move stealthily through the boggy undergrowth. The GPMGs were placed at the apexes of the triangle, and the NLAWs were spread about the sections. The Air Sentry was re-established, using the sergeant’s runner and one gunner, with orders only to open fire if we were under threat or had clearly been spotted.

As always, the civilian pickup truck approached from the east, works temporarily ceased, and it passed through unhindered and unaware of our presence. The day drew on, the shadows lengthened, and the works continued.

As the light finally died, and we drew the road sentries back towards the harbour, the position consisted of a myriad of staggered, four-feet deep slits, with bits of cam net, foliage and ponchos overhead, and a zig-zag path that was so far just a scraping of the forest floor. The sentries were doubled, the patrolling ceased, and all those spare continued to dig, the sounds of shovels and entrenching tools seeming inordinately loud.

In the distance, we could hear the thud of shell-bursts, and a few times we heard the faint buzz as some drone or other transited overhead, but they never lingered. We heard on the net that one of the other platoons in the company was being probed at their crossing site. Every crack in the forest brought pause to the digging, fingers gently tightening on machine gun triggers, but no enemy were to be seen through the murk of our HMNVs.

At the grey light of dawn, as the birds began their slow chirpings, we stopped digging and stood to. After half an hour, I made a quick round of the harbour to check progress. Each trench was now at least four feet deep, and some down to a full five or six feet, with good overhead cover from view. The communications trench was less than I’d hoped for but was still deep enough to crawl along with just a bit of webbing showing and was mostly covered from above by the thick pines. Content with our progress, I ordered the sentries to be pushed back out, and for the patrols to re-start. Anyone not on an essential duty was to spend the day resting, titivating the position where necessary, but with movement minimised. The morning passed slowly, the sun rising steadily above the pines, the river a distant gurgle. Intermittent booms sounded in the distance, and from the net we could tell that one of the other platoons was being pressed hard. Early afternoon came, a full 24hrs after we had been dropped off, and only 24hrs to go. Those soldiers unable to sleep improved their fire steps, continued adding to range cards, and waited.

Mid-afternoon, my signaller shook my arm to wake me. Two enemy probers had been seen, advancing along the road from the east on foot. I carefully shimmied forward and joined the section facing the bridge to get eyes on. The two probers were walking down the pine-lined road towards the bridge, their weapons carried low and unalert, unaware of the sentry position a few yards to their front. The sentries waited until they were almost on them before opening fire and dropped them before they knew what had happened. Silence followed, the probers contorted and motionless on the track.

I gave the order that the bodies were to be dragged off the track into the pines, hidden, and then the sentries were to withdraw back across the bridge before any larger force followed. The western sentries were also to return to the main perimeter. We watched as the eastern sentries heaved the corpses off the tarmac and into the undergrowth, and then came doubling back across the bridge, across the open ground, and into the harbour. Puffing, they told me that the two probers seemed to be older men, and that neither had been carrying a radio, nor any intelligence of value. They had covered the bodies with ferns. The afternoon drew on, and we waited, tenser now than before. An hour or so later, a buzzing noise began to grow. Looking up, we could make out the black speck of a drone hovering over the far side of the bridge. It flitted towards our side of the bridge, moving with jerky motions. The Air Sentry asked for permission to engage, but I declined, hoping beyond hope that our cover was sufficient. After a few minutes, the drone disappeared back over the trees eastward.

The afternoon marched on, the shadows lengthening again, and we waited. A growing sense of victory built in my mind; it looked like our hard-won plan was paying off. As the light began to die, the news came across the platoon net that more probers were approaching from the east. I shuffled to a forward trench, to see four enemy soldiers this time, advancing in pairs along either side of the road in the gloom. They seemed more alert than the previous attempt. They paused at the edge of the treeline, taking a knee and seeming to confer. Had something spooked them? As they left the safety of the treeline and approached the bridge, they began scanning their arcs with weapons half-raised. I waited until they were on our side of the bridge, and seemingly relaxing, then gave the order to fire. The weight of eight rifles and the two apex GPMGs, at less than a hundred meters, bore down on the squad. Two were felled instantly, and the other two disappeared into the scant cover afforded by the bridge abutments and the riverbank. One of the two that had made it cover had the clear silhouette of an antenna protruding from his kit.

Thinking fast, I order the section commander to keep up covering fire, and to prepare send a pair forward to clear them before they could send too much information back to their formation. Maintaining a staccato of rifle fire to suppress them, the section commander was just beginning to brief a pair for the assault when the enemy decided that enough was enough. They both broke cover and tried to dash back across the bridge to safety but were promptly dropped by a crescendo of GPMG fire. Silence. But not for long. Buzzing again, growing rapidly, then above us. We couldn’t see it, but it was there, and it could most definitely see the four dead probers, two on the bridge and two on the western road. This time, the drone didn’t withdraw. As the last of the light faded, a muffled burst of rifle fire erupted, not too far away, amongst the pines to the south, and was answered after a brief pause by a longer rattle of machine gun fire. A few minutes later, our fireteam patrol came crashing back into the harbour, narrowly avoiding some fratricide in the gloom with a hastily answered challenge, rifles held out to their sides.

The patrol commander reported that they had observed another four or so probers approaching along the home bank of the river to the south. They’d opened fire, hitting one, and then withdrawn. We were being probed from both sides of the river again. The scream of incoming artillery announced the next phase of the battle. A proximity shell burst amongst the trees, sending shards flying through the dark forest. We hunkered down, with the sentries risking their necks as they remained staring out into the darkness, HMNVs now on. This shelling continued throughout the night, a mix of proximity and point detonation intermittently crashing amongst the trees at a rate of one or two an hour. The overhead humming remained an almost constant. Nobody slept, all on utter edge, with those not on sentry continuing to eke out a few more precious inches of trench depth with their entrenching tools.

The dawn, with just twelve hours to go until we were relieved, brought the next probing attacks. A pair were seen trying to snurgle towards us along the road from the west, and were promptly beaten back by a burst of GPMG fire. A small party approaching through the pines to the north hit the top apex of the harbour, managing to kill one of my soldiers with an unfortunate shot to the head as they stood on the fire step, before they were driven back. Two more soldiers were struck by shrapnel from tree bursts, one lightly in the shoulder and one more seriously in the neck. The medics were able to, at great effort, shuffle between the wounded along the cover afforded by the communications ditch.

We were beginning to take casualties, and the enemy were now beginning to establish a clear image of our positions, so I decided to break radio silence and send a SITREP. Zero acknowledged and told us that as the other platoons were under similar attack, no reinforcements could be spared. They would see if they could raise anything from higher, but likely relief would still have to wait until the early afternoon as planned.

Either as the next phase of attack, or drawn on by our electronic emissions, the louder buzzing of dropper drones began. Again, our overhead cover prevented most of the drones from acquiring our trenches and deflected several of the grenades that were dropped. An FPV drone raced low across the bridge towards us. It came into the tree line, struggling to flit between the trees and our cam nets, and managed to lumber itself towards a slit. Just before impact, both occupants were able to throw themselves down a zig-zag in the communications trench and therefore only suffered from a bit of blast shock and some lower-limb frag. A second FPV drone tangled itself in the foliage of a dummy position before ineffectively detonating. We brought a couple of the dropper-drones down with rifle fire, and the others retreated. It was approaching mid-morning when the enemy, having seemingly decided that they knew our disposition well enough to expend more ammunition, began a more concerted bombardment. I slithered along the comms trenches between shells, trying to rouse some of the wavering troops. As with before, mortar bombs began to mingle with the artillery, and smoke bombs began to engulf our positions. Sporadic rifle fire continued from around the perimeter on all sides, keeping us fixed.

A shout went up from the east. Vehicles could be heard in the distance, and then two BMP-3s began to emerge into view, racing towards us down the road. All NLAWs were ordered to the eastern perimeter, and, with some cajoling, the operators monkey ran their way along the comms trenches.

The lead BMP opening up against the pines with its cannon, wounding one soldier with shrapnel. We held our fire, waiting for the first vehicle to cross onto the bridge, and then with a shout we opened up. The first NLAW missed by a whisker, whistling past the BMP and away to explode on the far bank. The second, fired almost simultaneously, struck the vehicle on the front left-hand side, tearing off road wheels and causing it to throw a track. It swerved, crashing into the parapet near the home bank and blocking the bridge, but continuing to blaze away with its cannon. The second BMP began to reverse backwards along the road towards the pines, firing as it went. Dismounts flooded from the back of the immobilised BMP, taking cover against the bank of the river, suppressed for a moment by a wall of rifle and GPMG fire. The third NLAW, our last, struck the stricken BMP for a second time, causing it to catastrophically explode, throwing its turret into the air and finally the river.

The second BMP reached the safety of the pines and began to hammer our position with its cannon. Its dismounts began advancing across the open ground to reinforce their comrades. Mortar bombs continued to fall, and we sustained more casualties from the cannon and rifle fire. I tried to order the other section commanders to reinforce the eastern perimeter, but comms were now intermittent, the radios squawking and spluttering. A dropper drone surged back towards us and dropped its load from a great height and into a slit. This time there was no bang, but a pop and hiss as smoke began to discharge. No, not smoke, gas. CS gas flooded a section of the trenches, and the occupants, whose respirators were buried deep in their bergens at the bottom of the trench, threw themselves over the parapet, gasping and weeping, to be struck by cannon and rifle fire. Our numbers diminished, we were losing the firefight on the eastern perimeter, and the enemy dismounts were surging across the bridge. It was getting desperate. To my utter despair, the sound of more vehicles, a mechanical groaning, began to reach us from the western road. It looked like we were about to be hit from the other side, and this time without NLAWs with which to answer them.

Then, joy beyond joy, the shout went up. They were Bradleys, they were friendly! The lead Bradley of the column raced through our perimeter, along the road, and towards the bridge. It opened fire with its 25mm chaingun against the dismounts coalescing by the riverbank, and we reinvigorated our own fire. The remaining BMP-3 hastily reversed away eastward before the Bradley could let loose an ATGM, firing a few token rounds as it left. The surviving enemy dismounts promptly ran a white rag up an AK-74 barrel and waved it from behind their cover, mortar bombs ceased, the perimeter fell silent. The game was up. The lead Bradley was trying to shunt the wrecked BMP-3 over the parapet as we emerged from the pines to take the prisoners back to the harbour, and more Bradleys were coming along the road from the west. I headed down to the road, and a Yank officer popped out of the turret of the second vehicle.

‘Heck, it looks like you guys gave them one hell of a bloody nose!’

Yes, I thought, we did. Well, at least this time.

Epilogue

As we handed over our positions to the Americans and readied ourselves for collection and onward tasking, I reflected on the previous few days and the previous few dreams. We had managed to hold our position this time, but again at the expense of several killed and many wounded. I still had lessons to learn, making sure that respirators were readily to hand being one of them, but I had learnt a lot, and quickly. I just hoped I would have as many attempts as possible again next time but, somehow, I doubted that I would.

Maj N Newman RE LCSC Writing Team.

Maj N Newman is a student and volunteer for the LCSC Writing team.

The Land Command and Staff College writing team has partnered with the Wavell Room. This new team of writers will produce an exciting range of PME articles.