Introduction

This year marked the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Since then, the non-use of nuclear weapons has remained the single most significant phenomenon of the nuclear age. Central to any discussion of global nuclear politics is the term nuclear taboo, which refers to a de facto prohibition against the first use of nuclear weapons. The nuclear taboo is not the act of non-use itself, but the deeply rooted belief that such use is illegitimate. This belief has endured for nearly 80 years, but the foundations are beginning to crack.

While the nuclear taboo has historically played a significant role in limiting the use of nuclear weapons, contemporary geopolitical shifts, rhetorical normalisation of nuclear use, and the weakening of nuclear diplomacy indicate a gradual erosion of this norm. What the world is now witnessing is an exponential increase in stockpiles, an escalation in nuclear rhetoric, and the erosion of arms control regimes. In the meantime, there is also an acceleration in the production and deployment of new nuclear weapons, with the rising geopolitical tensions.

Escalating Nuclear Rhetoric

Rhetoric holds a constitutive role when it comes to international politics. We can see how the power of language can shape issues such as national identity or give birth to social movements. One of the reasons why the tradition of nuclear non-use is a taboo, but not only a norm, is the subjective and intersubjective sense of taboo-ness. It manifests itself in how nuclear weapons have been discussed and interpreted over the years. How state actors speak about nuclear use is critical in altering the normative structures governing their use. For instance, in January 2024, Israeli Heritage Minister Amihai Eliyahu made headlines by commenting that a “nuclear attack” was an option in case of Gaza. His remark was eventually met with international outrage, which led to his suspension from cabinet meetings. More worryingly, it signalled a normalisation of extreme language when referring to conflict and war.

From the East…and the West

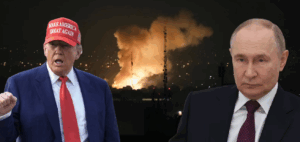

Only a matter of months after Eliyahu’s statement on Gaza, a similar shift in rhetoric was adopted by Russian President Vladimir Putin. He expanded Moscow’s nuclear doctrine to allow any conventional attack by non-nuclear states that were allied to a nuclear power to be met with a nuclear strike, as if they themselves were armed with nuclear weapons. In April 2025, the senior Iranian official Ali Larijani declared that Iran would be obliged to reevaluate its nuclear stance, should the Western powers act irresponsibly. This sharply contrasted with Iran’s former assertions that aimed to maintain its intentions were peaceful about its nuclear program. The erosion of conventional deterrence after direct strikes by Israel and the United States eventually developed into nuclear signalling.

Rhetoric from the West, particularly following the return of Donald Trump to power, has become more confrontational. This hardening stance has likely led to the changing perception of a threat to Iran, paving the way for miscalculation. Moreover, the growing normalisation of aggressive nuclear signalling across conflict zones increases the risk of escalation and misjudgment. In a recent statement, President Donald Trump defended the American strikes against Iran. He compared them to the use of nuclear weapons against Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which, according to him, brought an end to the Second World War. This type of language promotes the rhetorical normalisation of escalation by reframing the conversation around nuclear use, which eats away at the taboo over time.

A world that is rearming at an alarming rate

What makes this rhetorical shift more alarming is the material reality that accompanies it. As nuclear discourse grows more casual, nuclear states overtly invest in hard (military) power, as evidenced by the record levels of global military expenditure. In 2024, global defence spending was 9.4% greater than the previous year and set a new record of 2.718 trillion dollars – an exponential rise in global military expenditure. Meanwhile, conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza, and other regions persist in deepening the geopolitical rifts across the world. Global defence budgets grew by 37% between 2015 and 2024. The 2024 per capita figure for spending on defence had reached $334 – an amount not witnessed since 1990. These are the indicators of a more widespread trend in the world that instigates increasing insecurity and the emergence of great power competition.

The top five leading spenders in defence (the United States ($997B), China ($314B), Russia, Germany and India) account for over 60 percent of the world’s total. This military spending boom isn’t restricted to conventional forces alone. It is closely associated with the modernisation and growth of nuclear arsenals, further eroding the normative obstacles that have existed for eight decades.

In 2024, almost all nine nuclear-armed states increased their weapon stocks. Nearly 3,912 warheads are now mounted on missiles or aircraft. A further 2,100 are kept on high operational alert, suggesting they could be launched quickly. Presently, 90 per cent of nuclear weapons belong to Russia and the United States. But China is also rapidly boosting its arsenal, adding another 100 new warheads. Hans Kristensen, a senior fellow at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), believes that the world is gradually drifting away from disarmament and the nuclear reduction trend, which has been in place since the Cold War, will soon come to an end.

The demise of Arms Control

Global defence spending can’t be taken in isolation. It is symptomatic of a more profound crisis of the arms control regime and bilateral agreements worldwide. According to Dan Smith, director of SIPRI, the bilateral US-Russia agreement that had previously provided stability to nuclear relationships is quickly disintegrating. The New START treaty, the final substantial arms control accord between the two nations, will end in 2026; its renewal is uncertain.

Without a successor agreement, both states can considerably expand the quantity of deployed warheads. Russian plans will likely accomplish this via modernisation (placing several warheads on its existing stock of missiles) and through reactivating previously decommissioned silos. In the United States, warhead numbers could grow by rearming dormant launchers, deploying additional warheads to existing systems, and introducing new tactical nuclear weapons. These developments are already being framed as necessary responses to China’s expanding nuclear capabilities, as Beijing’s willingness to engage in formal arms control remains unclear. The absence of political will on the renewal of New START, the inability to make any progress on the FMCT, emerging questions on the credibility of the IAEA following the Israel-Iran 12-day war and the continued division in the non-proliferation treaty framework all indicate a crisis throughout the nuclear governance system.

The new arms race – quicker, faster, more deadly?

What’s alarming is that such risks are no longer confined to the traditional areas. The combination of artificial intelligence, cyber technologies, space-based systems, and quantum technology is changing the character of deterrence and shortening the time within which decisions can be made. This has increased the risks of miscalculation, which is more probable and even more devastating. According to SPRI Director Dan Smith, we are seeing the resurgence of Cold War-style competition and the newest form of arms race, which is quicker, more unpredictable, and exponentially more destabilising. Such volatility has also started to remodel nuclear thinking in other corners of the world, escalating regional tensions.

In 2024, Russia and Belarus reconfirmed that Russian nuclear weapons remained on Belarusian soil. The brief confrontation between India and Pakistan in May 2025 was a stark reminder that nuclear-armed states could still become embroiled in conflicts that can escalate very quickly. Also, as Matt Korda of SIPRI says, the increased proliferation of disinformation, the chance of rapid escalation, and the pre-delegation of launch authority all increase the dangers in such situations exponentially.

The current models used to predict nuclear war outcomes are incomplete. According to the report commissioned by Congress through the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, the current tools used to estimate the effects of a nuclear winter and long-term environmental damages are obsolete and inadequate. The report also concludes that the nuclear winter scenario that has dominated post-nuclear war modelling since the 1980s is outdated regarding its accuracy and assumptions on nuclear conflict – further evidence that the erosion of the nuclear taboo can’t be overlooked.

Conclusion

During this age of geopolitical insecurity, where international law and multilateral cooperation are under threat, the robustness and reliability of multilateral institutions can become the key to world peace and security. The past eighty years may be characterised by non-use, but the coming decades may not, unless conscious efforts exist to maintain the taboo. The renewal of multilateral participation, a commitment to arms control and opposition to the normalisation of aggressive rhetoric about the use of nuclear weapons must be implemented.

Shafia Batool

Shafia is a graduate of International Relations from the National Defence University and currently serves as a Research Intern at the Strategic Vision Institute (SVI) in Islamabad. Her research focuses on contemporary nuclear challenges, including the erosion of arms control regimes, shifting deterrence postures, and the fragility of the global disarmament agenda. She is particularly interested in how emerging security dynamics are reshaping the strategic landscape and what that means for stability, diplomacy, and the future of global order.