Incremental adaptation in modern warfare has astonished military observers globally. Ukraine’s meticulously planned Operation Spider Web stands as a stark reminder of how bottom-up innovation combined with hi-tech solutions can prove their mettle on the battlefield. It has also exposed the recurring flaw in the strategic mindsets of the great powers: undermining small powers, their propensity for defence, and their will to resist. Having large-scale conventional militaries and legacy battle systems, great powers are generally guided by a hubris of technological preeminence and expectations of fighting large-scale industrial wars. In contrast, small powers don’t fight in the same paradigm; they innovate from the bottom up, leveraging terrain advantage by repurposing dual-use tech, turning the asymmetries to their favour.

History offers notable instances of great power failures in asymmetric conflicts. From the French Peninsular War to the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, these conflicts demonstrate the great powers’ failure to adapt to the opponent’s asymmetric strategies. This is partly due to their infatuation with the homogeneity of military thought, overwhelming firepower and opponents’ strategic circumspection to avoid symmetric confrontation with the great powers.

On the contrary, small powers possess limited means and objectives when confronting a great power. They simply avoid fighting in the opponent’s favoured paradigm. Instead, they employ an indirect strategy of attrition, foster bottom-up high-tech innovation and leverage terrain knowledge to increase attritional cost and exhaust opponents’ political will to fight. Similarly, small powers are often more resilient, which is manifested by their higher threshold of pain to incur losses, an aspect notably absent in great powers’ war calculus.

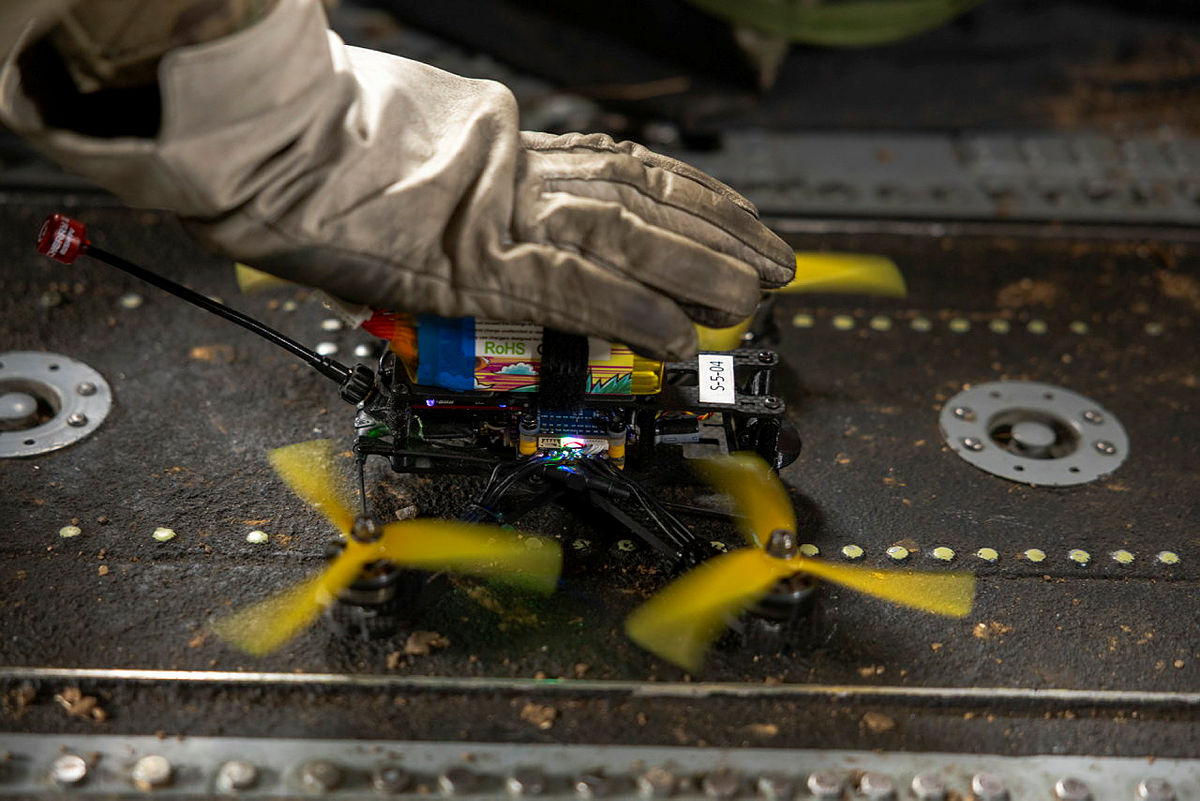

In the Operation Spider Web, Ukraine employed a fusion of drone technology with human intelligence (HUMINT) to attack Russia’s strategic aviation mainstays. Eighteen months before the attack, Ukraine’s Security Services (SBU) covertly smuggled small drones and modular launch systems compartmentalised inside cargo trucks. These drones were later transported close to Russian airbases. Utilising an open-source software called ArduPilot, these drones struck a handful of Russia’s rear defences, including Olenya, Ivanovo, Dyagilevo and Belaya airbases. Among these bases, Olenya is home to the 40th Composite Aviation Regiment—a guardian of Russia’s strategic bomber fleet capable of conducting long-range strikes.

The operation not only damaged Russia’s second-strike capability but also caught the Russian military off guard in anticipating such a coordinated strike in its strategic depth. Russia’s rugged terrain, vast geography and harsh climate realities shielded its rear defences from foreign incursions. Nonetheless, Ukraine’s bottom-up innovation in hi-tech solutions, coupled with a robust HUMINT network, enabled it to hit the strategic nerve centres, which remained geographically insulated for centuries.

Since the offset of hostilities, Ukraine has adopted a whole-of-society approach to enhance its defence and technological ecosystem. By leveraging creativity, Ukraine meticulously developed, tested and repurposed the dual-use technologies to maximise its warfighting potential. From sinking Russia’s flagship Moskva to hitting its aviation backbones, Ukraine abridged the loop between prototyping, testing, and fielding drones in its force structures.

Another underrated aspect of Ukraine’s success is the innovate or perish mindset. Russia’s preponderant technology and overwhelming firepower prompted Ukrainians to find a rapid solution to defence production. Most of Ukraine’s defence industrial base is located in Eastern Ukraine, which sustained millions of dollars’ worth of damage from Russia’s relentless assaults. Therefore, the Ukrainian government made incremental changes in Military Equipment and Weaponry (MEW) requirements by outsourcing military grade projects to private and non-traditional actors. By combining foreign procurements with indigenous solutions, Ukraine was able to establish 500 arms producers by 2024.

Moreover, the Ukrainian government propelled societal participation by launching a decentralised Brave 1 platform. The platform aimed to foster a military-civil fusion by connecting engineers and military units to turbocharge wartime innovation. According to SIPRI, nearly 1500 military-technology start-ups on drones, robotics, electronic warfare, communications, cybersecurity, and artificial intelligence (AI) have been registered on the platform. This makes it one of the most decentralised electronic data transfer (EDT) mechanisms, which bypasses prolonged bureaucratic cycles and brings indigenous technology into the hands of soldiers on the frontline.

Operation Spider Web demonstrates that, unlike great powers, small powers do not adhere to rigid war paradigms. Instead, they raise the cost of war by prolonging the conflicts, employing a strategy of attrition, exploiting terrain knowledge, and out-innovating the great powers in off-the-shelf technologies. Moreover, by ingeniously employing a fusion of old and new modalities of warfare, small powers exploit their adversary’s lack of flexibility. Rather than facing the adversary’s overwhelming firepower, superior technology and quantitatively irresistible manpower, small powers opt for enacting cheaper and adaptive battlefield frameworks.

Feature image credit: MOD

Shaheer Ahmad

Shaheer Ahmad is a Research Assistant at the Centre for Aerospace & Security Studies, Islamabad. He can be reached at cassthinkers@casstt.com