Pride goeth before the fall

War starts with a bluster. Whether it is with sacrifices in the temples, parades or press conferences, young men are sent to battle with pomp and ceremony. Then, they storm the forts or the beaches or the hilltops. They die, usually horribly, foolishly, from mistakes historians will later describe as avoidable. Lessons are learned – often, they resemble lessoned already learned in previous conflicts. Force generation and employment adapts. War ends. Another one begins, the cycle repeats itself. Academics write about military incompetence; others wax poetically about zoology.

One could argue that this pattern was to be expected in the past. For the majority of human history, fighting was barely a profession and militaries were lean establishment. Modern staffs, the “brain of the army” were a very late invention. Beforehand, learning was personal, military scholarship (often surviving centuries, receiving a stature akin to holy scripture) was anecdotal and amateurish.

We have surely advanced since. Everywhere military “back office” has ballooned, the fighting force has been professionalized. Military academies were established and some places, education programs were even enshrined by law. The military profession has moved from mainly art to science and art.

Militaries started trying to design themselves for the next war, establishing bureaucracies and process that move vast resources for that purpose. Yet militaries seem to keep getting it wrong. For a recent example, one should look east, the Russia-Ukraine war. Prior to that conflict, the Russian military, on its face, did everything right – it had a robust and professional back office, with many educational facilities, granting advanced degrees in military art and science to officers serving many years in their positions. It undergone and extensive reform converting it from a heavy conscripted force to a lean semi-volunteer army. It modernized, introducing new kit in every service and branch. It had many experienced officers from recent conflicts from Chechnya to Georgia and Syria to Ukraine itself. It was, on the paper at least, a serious threat, a force to be reckoned with. Yet, it too collapsed on the shores of reality and had to adapt and relearn lessons that were supposed to have already been known. This story is not unique. It repeats in many forms and languages. To the military professional observing from the ringside, this should raise serious questions about how militaries generate forces. Could it be that we are indeed incompetent? Are the tales of lions and donkeys true?

It is, of course, complicated

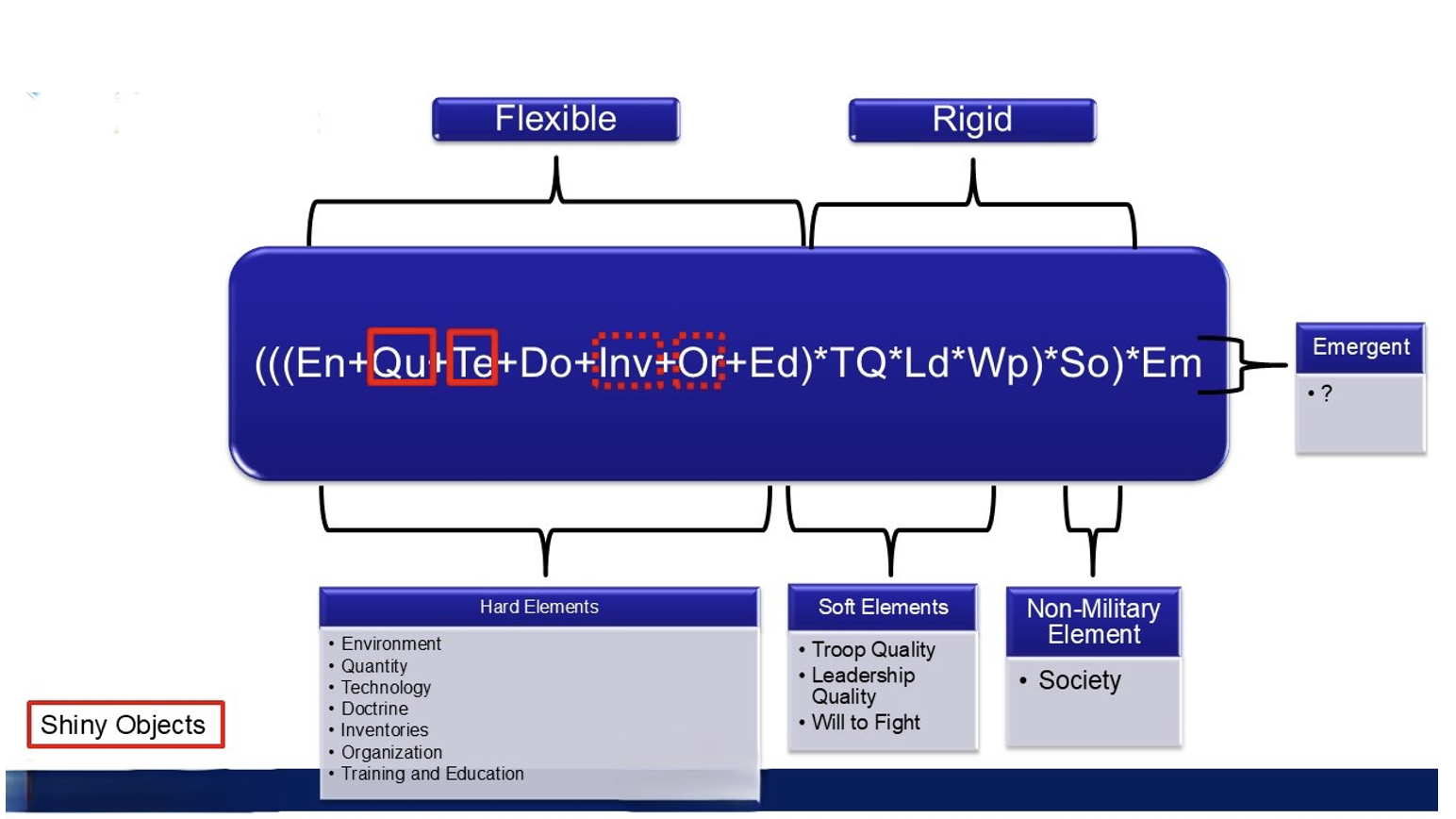

It is, indeed, complicated. Modern militaries like to engineer their forces. Force generation entails lengthy planning processes, involving many stakeholders and moving parts, over multiple years, meant to create the right force to win the first battle. To facilitate this design process, the military tries to holistically look at the various elements creating military power. These elements, referred to by the acronym DOTMLPF, describe everything that should go into the giant cocktail that is a military force – Doctrine, Organization, Training, Material, Leadership (and education), Personnel and Facilities. In recent years, a new ingredient was added to the recipe – Policy. With these powers combined, the right and lethel force is supposed to be created. This alphabet soup, however, only describes part of the very complicated picture and neglects the relationship between the various elements comprising military power. Depiction closer to reality would look something like this:

A military force is an organ (ideally) larger than the sum of its parts. These parts include “hard” elements (everything we can describe and measure), “soft” elements (other things we can’t comfortably describe, but rather talk with more hand waving about), non-military elements and unknown variables. Analysts and pundits tend to focus on the “shiny objects” that are easily measurable and sexy to discuss – technology and quantity of forces. Professionals also discuss the semi-shiny objects (inventories of consumables and organization of military forces). Real professionals who have somehow stumbled to PME institutions or doctrine departments also discuss education and doctrine. All these, however, reveal only parts of the solution to this intimidating equation – and not necessarily the important ones.

Paradoxically, the “hard” elements are flexible – meaning that mistaking them influences the overall outcome less than mistaking the “soft” variables. That is because the outcome of the sum of all hard elements is multiplied by the “soft” ones. Going to war with BTGs or brigades instead of divisions will not alter the final outcome. Same as fighting in the desert instead of the German plains or having technically inferior tanks. However, a force, armed to the teeth, will crumble without will to fight and competent leadership. The army’s will to fight will not suffice if the government chooses otherwise or society refuses to participate. And everything is then multiplied by the unknown. Saddam Hussain could not have known that his walk in the Kuwaiti park will soon be upgraded into a fight with the US (and allies), freshly liberated from the threat of Soviet invasion in Europe, but not yet enjoying the leisure of “peace dividends” and reduced force structured. Putin could not have known Zelensky would ask for ammunition and not an Uber. These unknown variables are common in war and can turn any plan and many years of force design on their head. If this is not enough, this equation describes “the blue force”. The same equation exists for every participant in the conflict – making war a very complicated problem with many variables, most of them unknown and unknowable to the poor staff planner.

This presents a problem too complex for planning. Even in an ideal world with no exogenous factors (e.g. service and national politics, personal egos, etc) No amount of intelligence, data or elaborate processes could describe all the variables mentioned above in a way that will facilitate creating the right force for future scenario. So how could militaries plan ahead? How could we get the right force to the fight – considering force generation could take a decade or more from RFI to warfighter?

The answer is, we can’t, we don’t and we shouldn’t try.

Military Gardening

Reality is less engineered than we like to think. From living organisims to societies, many things evolve organically. The more complicated an organization, the harder it is to plan. Modern militaries are among the most complex organizations in human society. Indeed, the development of the state was often induced by the requirement to make and support war. As such militaries evolve and grow, according to conditions that apply at the moment.

Militaries are often described as very conservative organizations, that resist change. And indeed, during peace time – from customs, units and uniform to weapon systems – militaries can be rather rigid. However, one could examine many militaries coming out of a long war and realize that they are very different from the organizations that went into it a few years prior. Whether it is the “Kitchener Army” in 1918, the greatly increased American military coming out of the Second World War or the COIN minded, MRAP equipped force that came out of the Global War on Terror. Militaries change dramatically during war – with varying degrees of success. That is because militaries, despite our aspirations to design them, behave more like living organisms or ecosystems. They grow in response to stimuli, adapt under pressure, and mutate unpredictably. Force design is not engineering — it’s gardening.

Joint Force Implications

The frustrated reader, having reached thus far must ask what should we do about it? If we can’t reliably and predictably “get it right”, should we just quit trying? Let things fall where they may and just go to war as we are (and wish everyone the best of luck)?

No. There is plenty to do, just differently.

First, we should acknowledge our inability to predict the future and design the right force for the right war. This acknowledgement (and the humility it must entail) should encourage us to create a resilient force. War reveals most of the variables in that mighty equation above. Once guns are blazing, we know the hard variables, the soft variable and many of the unknowns have revealed themselves. Also, many of the organizational constraints have vanished and money (ideally) is flowing. With conditions and incentives aligned, we can get to work designing the right force for the situation we are in. However, that means we need to be resilient enough to withstand the initial shocks of war. Thus, the force we build during times of peace should be strong and resilient. It should have sufficient redundancies of personnel and material to fight until the right force is designed and introduced.

Also, the economy of the state (and/or those of trusted allies) should be agile enough to leverage national resources and facilitate the mobilization and transition to a new force.

A direct result of the philosophy that designs the right force for the future, defense budgets are skewed towards research and development and procurement. Constantly investing in new tech creates a “rat race” of procurement and upgrading. The need to design equipment for an unknown scenario causes and ever longer list of requirements and ever growing price tags (and to these direct expenses one can add indirect expenses that are required from constantly implementing for new equipment in the force). The FY2024 DOD’s Research, Development, Test and Evaluation (RDT&E) budget is, in and of itself, toe-to-toe with Russia for the 3rd largest defense budget in the world. Adding military procurement and the sum is larger than the entire defense budget of China. The 2024 average expenditure on equipment (including R&D) for NATO countries is 32.3% of their defense budgets. This money should be spent differently.

Prioritizing resilience over innovation means slashing defense R&D and altering the way militaries think about procurement. Instead of researching the right (i.e. the newest, most sophisticated) defense tech before the war, militaries should concentrate on purchasing reliable existing and affordable kit in substantial numbers for as long as possible. Designing and building this equipment, militaries should use off-the-shelf technology, researched mostly by the civilian sector. They should concentrate relatively modest sums of military R&D budgets on basic science and engineering of select technologies that are not researched by the private sector (e.g. high-performance jet engines).

One core argument in this philosophy is that technology is a secondary element of military power and having the most advanced equipment does not influence achievement of victory despite the resources currently invested in it. A second argument is that existing tech, implemented quickly, in a manner that fits existing, known, operational requirements and distributed widely and in a timely manner to the force will give better results than exquisite tech, developed over decades and procured in small numbers.

As an example we can see that war in Ukraine is waged with mainly 1980’s and before military equipment and civilian technology, adapted and upgraded by the military during the war. We can also see that sustainment proves as key challenge. Thus, special care should be given to the procurement of consumables – fuel, ammunition, spare parts etc – which are consumed in larger quantities than previously planned.

The money saved from R&D and constant upgrades of equipment should be invested in redundancy and infrastructure – both civilian and military. Physical infrastructure and proper databases should be established and maintained to facilitate large conscriptions. Extra manufacturing capacity in the defense and civilian sectors should be paid for by the state (as was done during World War 2) to enable not only the plants and assembly lines, but the workforce and know how required for large scale production of equipment and ammunition. Large sums of money should be invested in training scientists, engineers and manufacturing workers. These will not all be directly hired by the defense industry but will be available for recruitment for planning new equipment and manufacturing it quickly during war.

Also, the military must have robust capabilities to analyze events, synthesize lessons and implement them. Military analysis during war should also consider the soft elements of military power. A force generated when the nation is fully mobilized, and casualties are accepted will be different from one that is designed for a conflict waged during times of civilian disagreement over the war.

The military’s ability to asses and analyze the war for lessons and properly implement them is not trivial – as we can see in the amount of time, blood and treasure it took for militaries in active combat to change their ways. The ability to change and adapt under fire is as important to victory as having the best and newest kit.

With a robust force that can withstand long duration of conflict, a civilian infrastructure that can engineer and manufacture the right equipment in large quantities once actual requirements are known, and a military establishment able to synthesize lessons to inform adaptation, the right military power can quickly be generated by the state.

Conclusion

The way modern militaries think about war is fundamentally wrong. We pay lip service to friction of war and the general unfeasibility of the future yet invest large amounts of resources and mental power in trying to engineer the force for future conflicts. This might be a direct derivative of the military-industrial complex and lead to waste of resources that could be invested better. It also brings the wrong force to war, and with the increase in prices of kit and personnel, it bring this force in poorer condition (smaller, leaner, more fragile) than in the past.

The article above offers an alternative philosophy for force generation and employment – developing a robust force and the infrastructure required for quick and agile adaptation during war. It offers do so with three main efforts – invest in large quantities of kit based on existing reliable technology, supported by large inventory of consumables; invest in civilian infrastructure to be mobilized in times of war to design and build the right force; invest in military capability to quickly analyze the situation, derive lessons and implement them “under fire”.

These three efforts are much simpler to discuss than to implement. Indeed, they are diametrically different from how many militaries think and act today. They require a change of mindset, bureaucracies and budgets – from pursuing the bleeding edge to strengthening the shaft of the spear. But whether we like it or not, reality shows us that military organizations are like a forest, and we are currently pruning bonsai trees.

Shmuel Shmuel

Shmuel Shmuel is the director of the Institute for Military Studies at the Israel Defense Forces’ Dado Center for Interdisciplinary Military Studies. He holds a BA and MA in History from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Follow him on X @shmuelsh23.

The opinions expressed in Shmeul's writing are not those of his employer.