The U.S. Navy faced multiple threats in an emerging technology environment. The past two years have offered many lessons about the efficacy of anti-ship ballistic missiles and unmanned platforms and we must identify and learn them. The lessons from Ukraine and Yemen are shaping fleet design for the next generation. Understanding the context of the lessons from the conflicts is crucial. What can the Battle of Lissa tell us?

In 1866, the navies of Austria and Italy fought near the island of Vis. Cutting the story short, the Austrians attacked in formations designed to aggressively ram the Italian ships, winning the battle despite an inferior status. The lessons of Lissa would impact naval design for the next 50 years. Before the Battle navies believed in the big gun. After Lissa navies were copying the Austrians and adding rams to new ships and developing ram-based tactics. But the lesson was wrong and the torpedo was the future.

As modern navies prepare for future conflict, it is important to understand the context of lessons, or risk drawing faulty conclusions.

Past as Prologue

For nearly 150 years, from De Ruyter until Nelson, naval tactics were static. Wooden ships fought each other with broadsides. Technical innovations squeezed more efficiency at the margins. Copper sheathing improved ships’ maneuverability with additional speed. The carronade increased the lethality of a ship’s broadside while decreasing cannon weight. These technological advances did not change the general tactic of pummeling ships with cannon broadsides.

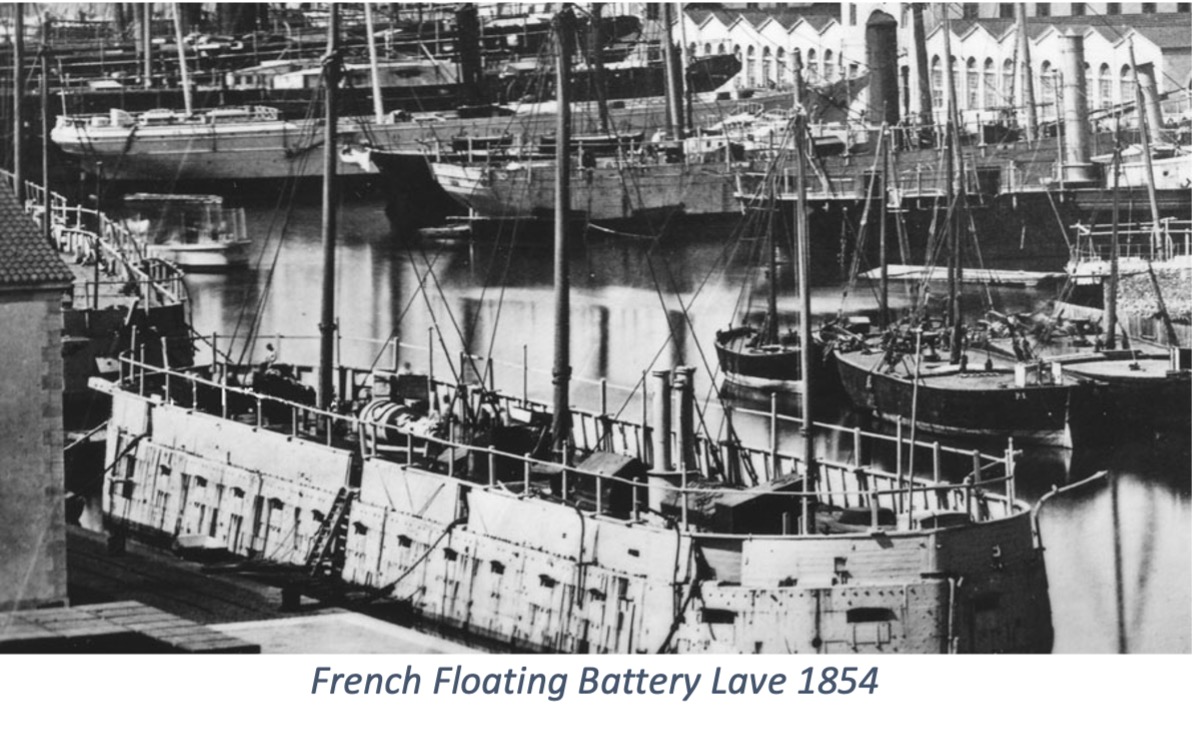

The 19th century was an age of technological revolution and emerging technology. In 1807, Robert Fulton tested his first steamboat in New York. This technology would continue to develop throughout the century. The steam engine revolutionized naval warfare because ocean-going warships were no longer beholden to the wind for maneuver. Developments in artillery meant that cannons were capable of firing explosive shells on flat trajectories to destroy wooden-hulled warships. By the 1840s, France and Britain sold these weapons to any nation that had the coin for them. Even the Republic of Texas Navy employed explosive shells fired from cannons. Explosive shells were great equalizers in naval combat. Armored warships appeared in the 1850s to counter improved artillery. France was the first nation to use armored warships during the Crimean War. Armored ships were impervious to the explosive shells of the age. The naval question of the second half of the 19th century was how to defeat armored vessels while naval guns improved sufficiently to threaten armored warships. The see-saw between warships’ armor and artillery lasted until the end of the battleship era.

Ramming

Austria, Prussia, and Italy fought a war in 1866. Most historians know the War of 1866 as the Austro-Prussian War, but in Italy it is known as the Third Italian War of Unification. Ashore, the Austro-Prussian War was decided at the battle of Sadowa (Königgrätz). In Italy, Austria defeated the Italian army at Custozza again and at sea at Lissa.

The Austrians were commanded by Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff. His officers all understood his battle plans and they had painted their ships different colours to help identification. Although Tegetthoff’s ships were smaller and carried smaller guns they would attempt to break the Italian line with three V-shaped formations. The first V composed his ironclads, the second V composed his large steam frigates, and the third V composed the fleet’s smallest ships.

Just before the battle the Italian commander, Admiral Persano shifted his flag to another ship. This caused tremendous confusion in the Italian Fleet because the shift was not planned for. Italian commanders looked to the old flagship for leadership and direction but found none.

Tegetthoff’s fleet broke the line in two places. The first V, led by Tegetthoff, engaged the central portion of the fleet. The second V of unarmoured ships broke the line near the Italian’s third division of ironclads. The second V formation of wooden ships of the line rammed the Italian Ironclads with little effect. Tegetthoff’s flagship, the Ferdinand Max, however, rammed two Italian ships. One of these ships was the Rei d‘Italia which sank within 2 minutes after ramming.

This tale of naval bravery an disguise the narrative of the battle. In his book The Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy, Dr. Sokol argued that, “in their excitement, the Italians often failed to load their guns before firing them.” According to estimates by historian John Hale, in his book Famous Sea Fights; the Austrians had a broadside of 1,776 pounds to the Italians 20,392 pounds.” The victory over the Italian fleet was telling; the Italians lost 612 officers and men, along with two ironclads, while the Austrians lost 38 officers and men, two of whom were captains.” Tegetthoff succeeded because his captains understood his plan and their crews were well trained. In contrast, the Italian fleet fought in confusion because their commander’s communications were not expected from a different ship.

But observers fixed on the ramming. Looking more broadly, there were multiple instances of ramming during the American Civil War. The Union Army commissioned a fleet of ramming ships. The CSS Albemarle sank union warships through ramming. Combined with Lissa’s inverse number of casualties to the number of guns many leaders believed the ram trumped the gun in the ironcladed future. Leaders drew the wrong lesson from the fight and generations of new ship construction included rams.

The 19th century was an age of technological revolution and emerging technology. In 1807, Robert Fulton tested his first steamboat in New York. This technology would continue to develop throughout the century. The steam engine revolutionized naval warfare because ocean-going warships were no longer beholden to the wind for maneuver. Developments in artillery meant that cannons were capable of firing explosive shells on flat trajectories to destroy wooden-hulled warships. By the 1840s, France and Britain sold these weapons to any nation that had the coin for them. Even the Republic of Texas Navy employed explosive shells fired from cannons. Explosive shells were great equalizers in naval combat. Armored warships appeared in the 1850s to counter improved artillery. France was the first nation to use armored warships during the Crimean War. Armored ships were impervious to the explosive shells of the age. The naval question of the second half of the 19th century was how to defeat armored vessels while naval guns improved sufficiently to threaten armored warships. The see-saw between warships’ armor and artillery lasted until the end of the battleship era.

Torpedoes

As ram mania grew, Robert Whitehead, an English engineer working in Austria-Hungary, was developing the weapon of the future, the self-propelled Whitehead torpedo. During the 1860s, three types of torpedoes were developed: the towed torpedo, the spar torpedo, and the Whitehead torpedo. The spar torpedo was the first practical torpedo and saw extensive service during the Civil War. The Whitehead torpedo was the first self-propelled torpedo. It made the towed and spar torpedoes obsolete. Whitehead’s torpedo had a speed of 7 knots; by 1870, it had a speed of 17 knots. Technical and design improvements continued to increase the speed, range, and warhead size, and it remains a capable weapon today.

The Austrian and French Navies created the Jeune Ecole. The naval strategy for the weak. It imagined a fleet of coastal battle ships, torpedo ships, and fast rams to defend the coast. These ships could be built cheaper than heavy armored ships and the theory was small fast ships armed with torpedoes would enable a weaker navy to deny their enemy the ability to blockade their coast and interfere with coastal commerce. While ships designed for guerre de course attacked the enemy’s trade.

Admiral Auberge, the French Godfather of the Jeune Ecole sent officers to observe Austrian naval exercises. Reading their reports, he exclaimed that the French Jeune Ecole was theoretical, but that the Austrian Navy practiced it. Annual Austrian naval exercises trained the navy on these tactics.

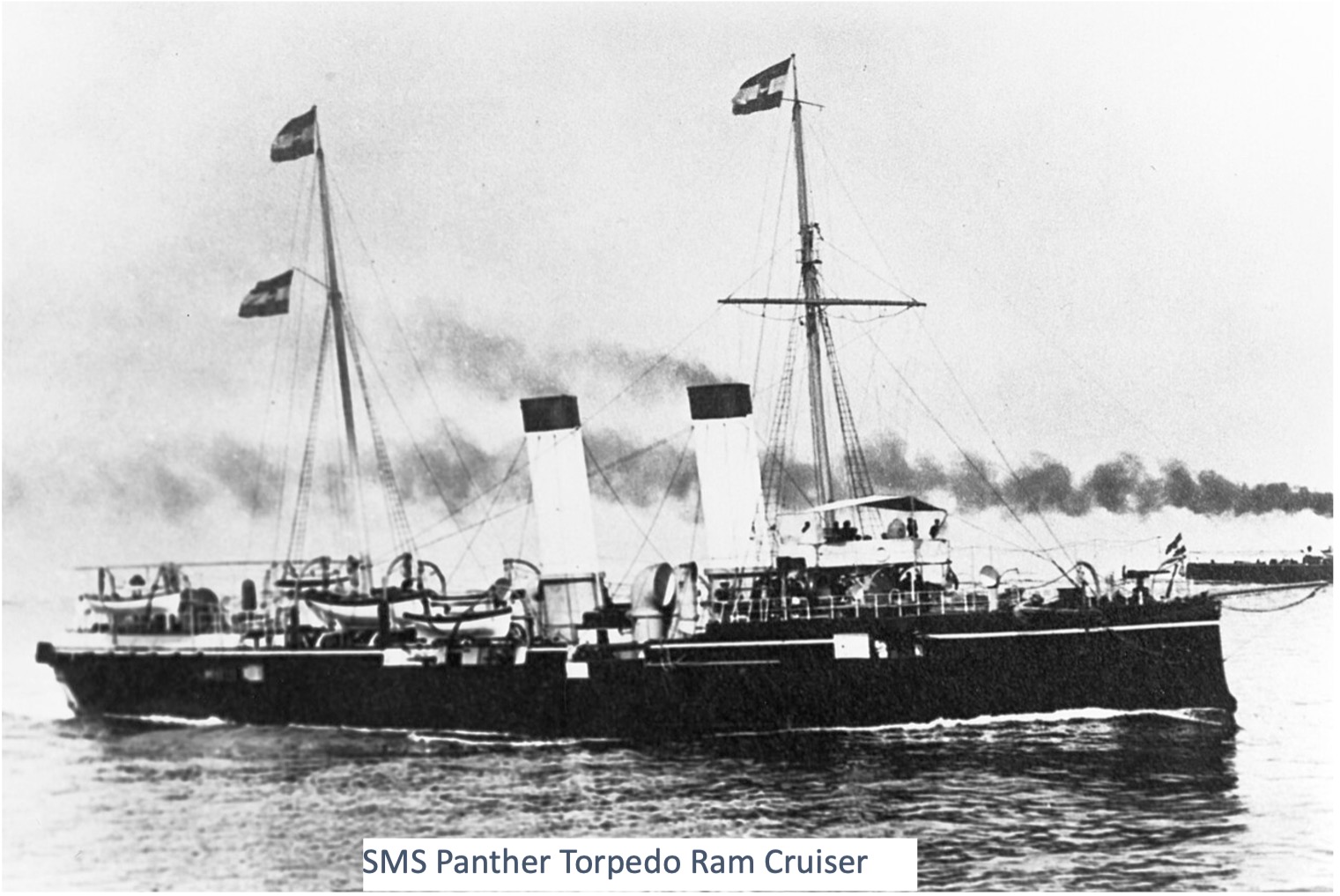

A weakness of French force design was that their fast torpedo boats were not good sea-faring vessels. Voyages in the stormy Bay of Biscay or transits from Toulon to Brest were incredibly uncomfortable. It was doubtful that the torpedo boats could complete their missions in heavy seas. Austria had fast torpedo boats but had also designed 1500-ton torpedo ram cruisers which were larger and equipped with a ram and four torpedo tubes.

The torpedo could reach an opponent beyond the range of a ram and with less difficulty than two maneuvering ships. Austrian exercises demonstrated success with the torpedo. Robert Whitehead, an English engineer living in Austria-Hungary invented the torpedo. The Haus-Hof-und Staats Archiv contains multiple requests for teams of naval officers from most countries to learn about Austrian torpedo production and tactics. In 1870 Whitehead traveled to Great Britain to demonstrate the torpedo’s capabilities for the Royal Navy. Two Royal Navy Captains that believed in the superiority of the ram observed the tests. They were convinced of the torpedo’s future. The Royal Navy invested in the torpedo and Whitehead licensed the torpedo for production in Great Britain. The navies expected the next Salamis. Instead the battles of Port Arthur and Tshushima demonstrated the future naval warfare was the torpedo.

Conclusion

The battle of Lissa led many officers down the ram rabbit hole. For nearly 30 years, ships maintained the vestige of the ram. All the while, the size and capability of the guns and torpedoes improved. It is important to study design failures to understand that not every technology is going to work as expected, and to look at a battle deeper. During the 1860s, navies were exploring ways to defeat armored warships. Ramming worked in a few very specific incidences. At Lissa, the Austrian ships fought with the Nelson touch breaking the Italian line, supporting each other, and wreaking havoc.

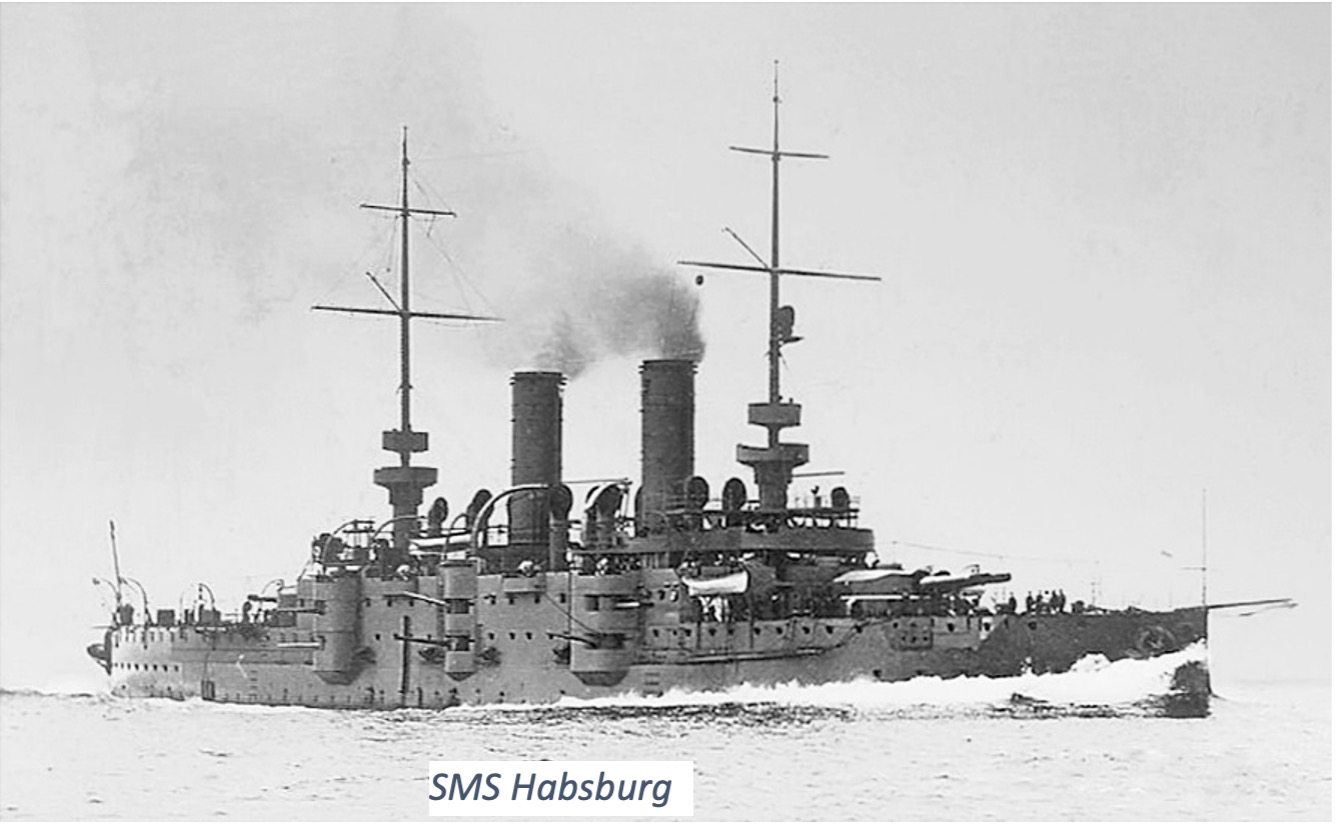

Mahan’s writings on sea power brought the big gun battleship back into focus for sea control amongst the great powers. The Austrian battleship SMS Hapsburg, commissioned in 1902, lacked a ram. She looked like the typical pre-Dreadnought covered in guns of every shape and size, but her bow lacked the sweeping lines of the 19th century ram ships.

Navies of the late 19th century spent 50 years chasing the chimera of the ram while the torpedo was developing. By 1914, the threat of torpedoes had created the torpedo boat, torpedo boat destroyer, and torpedo blisters on battleship hulls. Much like Nelson at Trafalgar, Tegetthoff knew he could break the enemy’s line and destroy them in a pell mell battle. The correct lessons from the battle were a well-trained fleet aggressively commanded will defeat a poorly led, poorly trained fleet and that the successor to the ram was the new torpedo.

Jason Lancaster

Jason Lancaster is a US Navy Surface Warfare Officer. He has served in amphibious ships, destroyers, and a destroyer squadron. He graduated from the US National War College in June 2025. He has an MA in History from the University of Tulsa and a BA in International Affairs from Mary Washington College