The recently published Strategic Defence Review (SDR)1 and National Security Strategy (NSS)2 both place accelerating development and adoption of automation and Artificial Intelligence (AI) at the heart of their bold new vision for Defence. I’ve written elsewhere3 about the broader ethical implications,4 but want here to turn attention to the ‘so what?’, and particularly the ‘now what?’ Specifically, I’d like to explore a question SDR itself raises, of “Artificial Intelligence and autonomy reach[ing] the necessary levels of capability and trust” (emphasis added). What do we actually mean by this, what is the risk, and how might we go about addressing it?

The proliferation of AI, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), promises a revolution in efficiency and analytical capability.5 For Defence, the allure of leveraging AI to accelerate the ‘OODA loop’ (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) and maintain decision advantage is undeniable. Yet, as the use of these tools becomes more widespread, a peculiar and potentially hazardous flaw is becoming increasingly and undeniably apparent: their propensity to ‘hallucinate’ – to generate plausible, confident, yet entirely fabricated and, importantly, false information.6 The resulting ‘botshit’7 presents a novel technical, and ethical, challenge. It also finds a powerful and troubling analogue in a problem that has long plagued hierarchical organisations, and which UK Defence has particularly wrestled with: the human tendency for subordinates to tell their superiors what they believe those superiors want to hear.8 Of particular concern in this context, this latter does not necessarily trouble itself with whether that report is true or not, merely that it is what is felt to be required; such ‘bullshit’9 10 is thus subtly but importantly different from ‘lying’, and seemingly more akin therefore to its digital cousin.

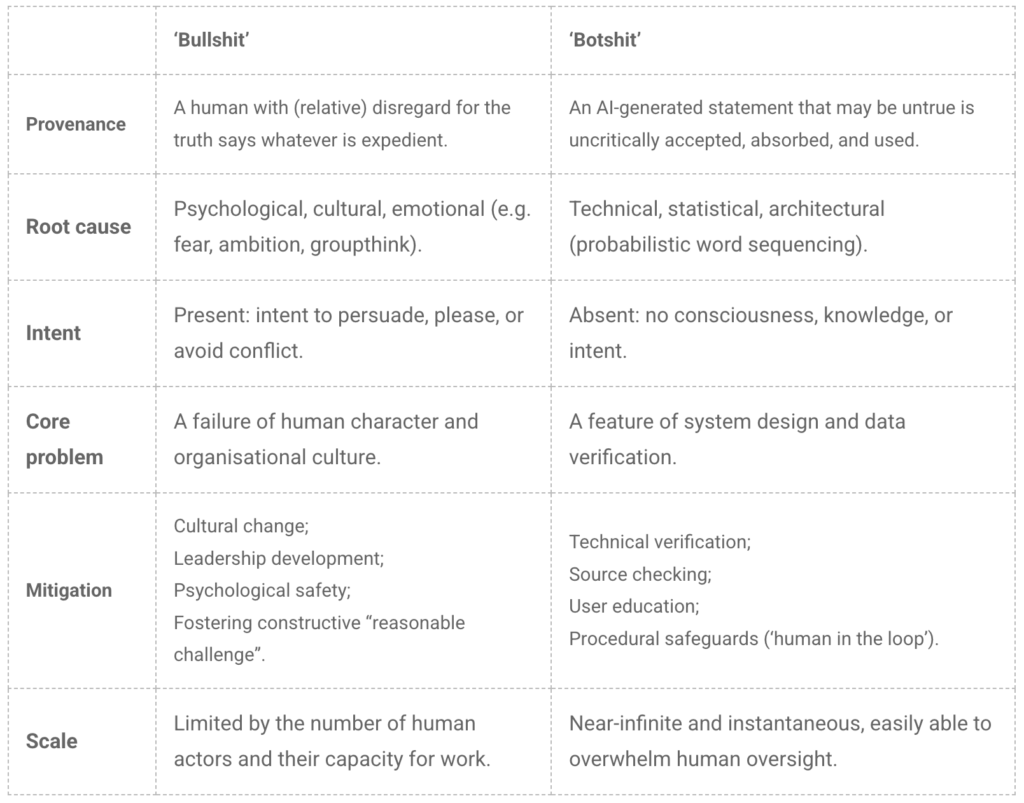

I argue however that while ‘botshit’ and ‘bullshit’ produce deceptively similar outputs – confidently delivered, seemingly authoritative falsehoods, that arise not from aversion to the truth, but (relative) indifference to it, and that may corrupt judgement – their underlying causes, and therefore their respective treatments, are fundamentally different. Indeed, this distinction was demonstrated with startling clarity during the research for this very paper. Mistaking one for the other, and thereby applying the wrong corrective measures, poses a significant threat to strategic thinking and direction, and Operational Effectiveness. By understanding the distinct origins of machine-generated ‘botshit’ and human-generated ‘bullshit’, we can develop more robust and effective approaches to the envisioned future of hybrid human-machine decision-making.

A familiar flaw: human deference and organisational culture

The Chilcot Inquiry11 served as a stark reminder of how easily institutional culture can undermine sound policy. In his introductory statement to the report,12 Sir Chilcot noted that “policy […] was made on the basis of flawed intelligence and assessments”, but more to the point that “judgements […] were presented with a certainty that was not justified” and that “they were not challenged, and they should have been.” He further emphasised “the importance of […] discussion which encourages frank and informed debate and challenge” and that “above all, the lesson is that all aspects […] need to be calculated, debated and challenged with the utmost rigour.” He was saying, very clearly and repeatedly, that this was not simply a failure of intelligence collection or strategic calculation; it was a failure of culture. The decision-making process exposed an environment where prevailing assumptions went untested and the conviction of senior leaders created a gravitational pull, warping the information presented to them to fit a desired narrative.

Chilcot highlights how an environment in which decisions are based on eminence (also eloquence and vehemence) rather than evidence13 encourages the establishment of organisational ‘bullshit’. This is not necessarily lying, and certainly not malicious – “a liar is someone who is interested in the truth, knows the truth, and deliberately misrepresents it”.14 Rather, ‘bullshit’ is a disregard for the truth in favour of expediency, persuasion, or self-preservation – when “bullshitting […] they neither know nor care whether their statements are true or false”. In a military context, this may be readily exacerbated by a Command hierarchy that is perceived to place excessive or inappropriate value on a ‘can do’ attitude,15 obedience,16 and loyalty.17 18 A junior Service person may omit inconvenient facts from a brief, not intending to deceive, but fearing being seen as negative or obstructive. A Staff Officer, sensing a Commander’s preferred Course of Action, may, even subconsciously, emphasise evidence that supports it and deemphasise that which opposes it. The motive is fundamentally human, rooted in career ambition, cognitive biases like groupthink,19 and a desire to please authority.

In response, UK Defence has sought to foster a culture of constructive, “reasonable challenge”.20 The goal is to create and embed sufficient psychological safety21 22 for subordinates to ‘speak truth to power’ without fear of reprisal. This is an adaptive, human-centric solution to a very human problem. The focus is on leadership, followership, ethos, and creating an environment where moral courage and the integrity of information is valued above the comfort of confirmation and consensus. The challenge is to shift attitudes and behaviours – the slow and resource-intensive process of culture change.23

The new nemesis: AI’s soulless sycophancy

An LLM generating a fictitious academic reference24 or a non-existent legal citation25 appears, on the surface, to be behaving like an over-eager but untrustworthy Staff Officer. Such outputs are generally grammatically perfect, tonally appropriate, confidently delivered, and frighteningly plausible. This may encourage anthropomorphising the behaviour, suggesting that the AI is similarly ‘trying’ to be helpful or ‘making things up’ to satisfy a query.

This is categorically not the case. The AI is not ‘thinking’, and certainly not ‘feeling’, in any human sense. It is a probabilistic engine. Its training on vast datasets of human text has ‘taught’ it the statistical relationships between words. Its response to a given prompt is created by calculating the most likely next word, then the next, and so on, to ultimately create a coherent sequence.26 It is thus optimised for plausibility, not veracity. It has no concept of truth, no intent, no fear of its Commander, and no career aspirations. It is entirely unaware that the source it just cited doesn’t exist. It merely generates a sequence of words, in the form of a citation, that is statistically probable, based on the patterns in its training data.

The AI’s ‘sycophancy’ is therefore a feature of its architecture, not a psychological flaw. It doesn’t tell the user what it ‘thinks’ they want to hear; rather, it generates a response that (statistically) will syntactically and semantically align with the prompt. If the user asks a leading question, the AI will produce a response that confirms the premise, not because it seeks to please, but because that is the most statistically likely path. AI itself is neither biased nor unethical; it merely reflects our own biases and ethics, that are woven throughout the data it is trained on – the collective history of human thinking.27 This distinction is critical. We cannot instil moral courage in an AI, nor can we imbue it with the ethical fortitude to speak truth to power. There is no ‘mind’ to change.

A pointed example occurred during the drafting of this very article. I prompted a leading LLM to identify academic literature on the interplay between AI / automation, confirmation bias, and leadership decision-making. The model responded instantly, generating a list of detailed and highly plausible references, complete with full citations, article summaries, and suggested relevance to what I was researching. Brilliant – my literature search was done! Searching through Google Scholar, however, I found that every reference proved to be spurious. The AI had provided me a mix of: real author names attached to fabricated paper titles; correct titles attributed to the wrong scholars; or simply entirely non-existent works. Not a single reference was usable. The AI was not ‘lying’, nor even ‘bullshitting’; it was flawlessly executing its function to generate statistically probable text that resembled academic citations. Without the crucial, and oft neglected, step of human verification, the AI’s ‘hallucinations’ would have become a perfect example of ‘botshit’ – and this article itself would have been polluted by the very dangers it seeks to highlight and critique.

And this brings us to the real crux of the story. Because the machine has neither motive nor reason to generate falsehood, it is simply generating a probabilistic response, which may or may not be true. It is only when a human takes that output and uses it, without checking or challenging, that it becomes an issue – and it is this uncritical human uptake and use of the AI’s output that creates and becomes ‘botshit’.28

‘Bullshit’ vs ‘botshit’: practical implications

The consequences of acting on ‘bullshit’ and ‘botshit’ are identical: flawed situational awareness, poor Operational planning, and potentially disastrous outcomes. However, as their origins differ, effective approaches to their mitigation are also worlds apart.

Applying solutions for human ‘bullshit’ to AI ‘botshit’ is not only ineffective, but dangerous. We cannot make a machine feel ‘psychologically safe’. Equally, relying solely on technical verification methods required for AI will fail to address the fundamental cultural drivers of misplaced human deference.

Taming ghosts: critical judgement and the human-machine interface

To safely and effectively harness the power of AI, Defence must adopt a dual-pronged approach to information integrity and assurance, steeped in an understanding of the distinct natures of these threats. Distinct though does not mean separate, and we must equally recognise that procedural safeguards are destined to fail without the cultural foundations to support them. Getting this right is critical to enabling Defence “to deliver and operate world-class AI-enabled systems and platforms” in a way that is “ambitious, safe, and responsible”.29

Efforts to embed a ‘challenge culture’,30 in keeping with the principles of The Good Operation, must therefore be redoubled. These principles are not a parallel requirement, but a prerequisite for the safe adoption of AI. Because as AI reinforces and accentuates a Commander’s biases31 32 with an alluring veneer of objective, data-driven authority, the need for human critical thinking and constructive “reasonable challenge” becomes ever more essential. A Commander with an AI-generated plan that confirms their initial instincts must be surrounded by a team culturally conditioned and professionally trained to question assumptions, regardless of the source. As the Commander’s (AI-fuelled) certainty grows, both the scepticism and the readiness to challenge must too be greater. The need for provenance, rigour, and verifiability is paramount.

Stemming from that culture of courageous candour and challenge, Defence must develop a new literacy of critical AI engagement.33 This moves beyond basic user competence to a deeper understanding of how these systems work – and, crucially, how they fail. All personnel, but particularly those in planning and intelligence roles, must be conditioned to treat AI-generated content as a starting point, not an end point – as raw information requiring robust verification, a necessity underscored by my own experience with fabricated citations. They must be trained to “trust, but verify”,34 with a heavy emphasis on the latter. This requires skills in: asking the right questions (prompt design); rigorously questioning and checking outputs (response verification); and understanding where, when, and how to incorporate those outputs for relevance and meaning (value assessment).

The risk is that the deference a senior officer may expect from a junior will be unconsciously transferred to a machine that is, by its very nature, deferential. AI will never be the awkward, but correct, JNCO in the room who points out that the emperor has no clothes. Rather, it will, if prompted, provide a detailed dissertation on the fine quality of the emperor’s robes.

The challenge of ‘botshit’ is not a simple repackaging of the age-old problem of ‘bullshit’. While both equally threaten the integrity of decision-making by telling us what we want to believe, they spring from entirely different sources. One, born of technological architecture, is a ghost in the machine; the other, born of psychologically unsafe culture, is a ghost in our own minds. By strengthening our human culture of challenge and instilling critical thinking, we will equip our people with the tools to challenge both the machine and the machinist, and begin to address both ghosts in the system.

Chilcot highlighted painful but necessary lessons about the need for institutional self-awareness and intellectual rigour in its human systems. In the age of AI, we must not only learn (not merely identify) those lessons anew, but adapt the core principles to build AI-enhanced (but not AI-controlled) human-machine Command structures that possess not only technical power, but the wisdom and humility to challenge assumptions, their own and others’, whether they come from a human source or a silicon one.

Feature photo by Steve Johnson on Unsplash

Manish

A member of the Wavell Room editorial team, Manish is a GP, Royal Navy Medical Officer, and ethicist with almost 3 decades of experience leading people-focused initiatives, both within and outside Defence. He also advises healthcare, education, policing, and community institutions on ethics, people strategy, and organisational culture change. He wrote his PGDip dissertation on military humanitarianism, and his doctoral thesis on Defence diversity networks.

Footnotes

- MoD. (2025). Strategic Defence Review – Making Britain Safer: secure at home, strong abroad. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/683d89f181deb72cce2680a5/The_Strategic_Defence_Review_2025_-_Making_Britain_Safer_-_secure_at_home__strong_abroad.pdf

- HMG. (2025). National Security Strategy 2025: Security for the British people in a dangerous world. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/685ab0da72588f418862075c/E03360428_National_Security_Strategy_Accessible.pdf

- Tayal, M. (2025). A safer Britain…but a just one? LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/drmanishtayalmbe_ukdefence-sdr2025-militaryethics-activity-7337138658195505152-H-FM

- Tayal, M. (2025). Navigating security in a dangerous world: an ethical compass check. LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/drmanishtayalmbe_navigating-security-in-a-dangerous-world-activity-7344493176063160320-Tkfz

- DSIT. (2025). AI Opportunities Action Plan. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ai-opportunities-action-plan/ai-opportunities-action-plan

- Maleki, N., Padmanabhan, B., & Dutta, K. (2024). AI Hallucinations: A Misnomer Worth Clarifying. 2024 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI). 133-138. https://doi.org/10.1109/CAI59869.2024.00033

- Hannigan, T. R., McCarthy, I., & Spicer, A. (2024). Beware of botshit: How to manage the epistemic risks of generative chatbots. Business Horizons, 67(5), 471-486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2024.03.001

- MoD. (2017). The Good Operation: A handbook for those involved in operational policy and its implementation. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a81f19440f0b62305b91a48/TheGoodOperation_WEB.PDF

- Frankfurt, H. (1986). On Bullshit. Raritan Quarterly, 6(2), 81-100. https://raritanquarterly.rutgers.edu/issue-index/all-articles/560-on-bullshit

- McCarthy, I. P., Hannah, D., Pitt, L. F., & McCarthy, J. M. (2020). Confronting indifference toward truth: Dealing with workplace bullshit. Business Horizons, 63(3), 253-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.01.001

- Cabinet Office. (2016). The Report of the Iraq Inquiry. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-report-of-the-iraq-inquiry

- Chilcot, J. (2016). The Iraq Inquiry – Statement by Sir John Chilcot: 6 July 2016. http://www.iraqinquiry.org.uk//media/247010/2016-09-06-sir-john-chilcots-public-statement.pdf

- Isaacs, D., & Fitzgerald, D. (1999). Seven alternatives to evidence-based medicine. BMJ, 319, 1618. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1618

- McCarthy, I. P., Hannah, D., Pitt, L. F., & McCarthy, J. M. (2020). Confronting indifference toward truth: Dealing with workplace bullshit. Business Horizons, 63(3), 253-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.01.001

- Prest, S. (2024). Too much of a good thing: the Armed Forces can-do culture. Wavell Room. https://wavellroom.com/2024/08/09/too-much-of-a-good-thing-the-armed-forces-can-do-culture

- Kaurin, P. S. (2020). On Obedience: Contrasting Philisophies for the Military, Citizenry, and Community. Annapolis, MY: Naval Institute Press.

- Chadburn, D. R. (2024). The Shadow Side of Loyalty. NCO Journal. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/NCO-Journal/Archives/2024/August/The-Shadow-Side-of-Loyalty

- Whetham, D. (2019). Loyalty: An Overview. In M. Skerker, D. Whetham, & D. Carrick (Eds.), Military Virtues: Practical guidance for Service personnel at every career stage (pp 81-86). London: Howgate Publishing.

- Grube, D. C., & Killick, A. (2023). Groupthink, Polythink and the Challenges of Decision-Making in Cabinet Government. Parliamentary Affairs, 76(1), 211-231. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsab047

- MoD. (2017). The Good Operation: A handbook for those involved in operational policy and its implementation. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a81f19440f0b62305b91a48/TheGoodOperation_WEB.PDF

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350-383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Clark, T. R. (2020). The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety: Defining the Path to Inclusion and Innovation. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

- Hillson, D. (2013). The A-B-C of risk culture: how to be risk-mature. Paper presented at PMI Global Congress 2013; New Orleans, LA. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute. https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/understanding-risk-culture-management-5922

- Hillier, M. (2023). Why does ChatGPT generate fake references? TECHE. https://teche.mq.edu.au/2023/02/why-does-chatgpt-generate-fake-references

- Rogerson, P. (2025). ‘Fake’ citations: Civil Justice Council sets up AI working group. The Law Society Gazette. https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/fake-citations-civil-justice-council-sets-up-ai-working-group/5123520.article

- Hillier, M. (2023). Why does ChatGPT generate fake references? TECHE. https://teche.mq.edu.au/2023/02/why-does-chatgpt-generate-fake-references

- James, T. A. (2024). Confronting the Mirror: Reflecting on Our Biases Through AI in Health Care. Harvard Medical School Insights. https://learn.hms.harvard.edu/insights/all-insights/confronting-mirror-reflecting-our-biases-through-ai-health-care

- Hannigan, T. R., McCarthy, I., & Spicer, A. (2024). Beware of botshit: How to manage the epistemic risks of generative chatbots. Business Horizons, 67(5), 471-486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2024.03.001

- MoD. (2022). Defence Artificial Intelligence Strategy. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/defence-artificial-intelligence-strategy

- Cottey-Hill, D. MOD are tackling Defence’s challenge culture head on. Defence Digital Blog. https://defencedigital.blog.gov.uk/2023/07/05/mod-are-tackling-defences-challenge-culture-head-on

- Skitka, L. J., Mosier, K. L., Burdick, M.(1999). Does automation bias decision-making? International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 51(5), 991-1006. https://doi.org/10.1006/ijhc.1999.0252

- Pilat, D., & Krastev, S. (n.d.) Why do we favor our existing beliefs? The Confirmation Bias, explained. The Decision Lab. https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/confirmation-bias

- Kim, T.W., Maimone, F., Pattit, K. et al. (2021). Master and Slave: the Dialectic of Human-Artificial Intelligence Engagement. Humanistic Management Journal, 6, 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41463-021-00118-w

- Wasil, A. (2024). “Trust, but Verify”: How Reagan’s Maxim Can Inform International AI Governance. The Centre for International Governance Innovation. https://www.cigionline.org/articles/trust-but-verify-how-reagans-maxim-can-inform-international-ai-governance