Why is adopting gender-neutral language so difficult for the Armed Forces? In 2017, a training establishment was widely ridiculed in the press for having suggested a fairly mild list of gender neutral terms to replace words such as ‘chaps’ and ‘manpower.’ Alarmingly, much of the opposition came from serving personnel who branded it “the daftest thing ever” and took to social media to decry the move. And last year, the news broke that the Army may (or may not) still refer to sewing kits as ‘housewives’. This led to a further media frenzy, roughly divided between condemnations of institutional sexism and cries of “political correctness gone mad”. But does it even matter? The short answer is yes.

Gendered language does more than just give offence, although avoiding this is surely a reasonable aim in itself. The real effects are far more subtle and insidious, perpetuating stereotypes, damaging recruitment and retention and undermining the ability of the Armed Forces to harness the talents of its people. At the most severe, it affects mental health, damages unit cohesion and undermines operational effectiveness. But language is emotive and deliberately changing its use is difficult. Clumsy attempts to do so may merely exacerbate the problem they are trying to solve.

To understand the effects of gendered language, we need to understand the subtle and often unnoticed ways in which words affect us. In one experiment, college students were asked to construct sentences out of lists of scrambled words.1 One group’s list contained words associated with old age, such as worried, old, grey, lonely and wrinkle. After taking the test, students walked back down the corridor more slowly than students given tests that contained words associated with youth. Reading words associated with old age had made them act old. But when questioned, none of the students was aware either of their behaviour or that there had been any age-related words in the test. They had been primed, unconsciously.

Unconscious Priming

Other examples of these priming experiments are even more stark. In the US, African Americans have for a long time been portrayed as academically weak. A study found that simply asking black students to identify their race before a test halved the number of correct answers they gave. Reminding them of their race was enough to trigger the associations of academic underperformance, and in response they underperformed. Once again, none of them was aware of this. When questioned, they blamed their poor performance on simply not being good enough and their race wasn’t mentioned. 2

Unconscious biases run deep. The Implicit Association Test, or IAT, is a revealing measure of these and is worth spending half an hour on for anyone who thinks they are free from bias. There are tests for various biases including age and race. For example, almost everyone, male and female, find it harder to associate career-related words with women and family-related words with men, however scores on these tests can be altered through positive priming. One student took the test repeatedly but only made the correlation of ‘achievement’ and ‘black people’ for the first time after watching the Olympics. Priming is unconscious but very powerful.

It is not hard to see how gendered language can have the same effect. Imagine that the members of a promotion board have just been discussing manpower challenges, man-management and the latest guidance from the manning cell. ‘Man’ has been planted in their head, and the chances of a woman being selected for promotion have just diminished. Anyone who has sat on a board will deny this vigorously, but remember the examples above; priming is unconscious. We aren’t always aware that it is happening.

Masculine Terminology

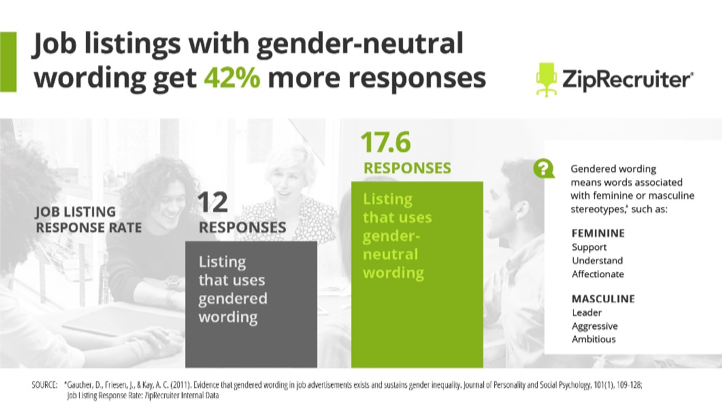

The same is true when roles are outlined in traditionally masculine terms. The Implicit-Association Test shows that most people associate words such as active, ambitious, challenging, confident, decisive, determined and leader with men. This presents a further issue for the promotion board looking for candidates who demonstrate precisely such qualities. Once again, priming diminishes the woman’s chances. Furthermore, job descriptions containing traditionally masculine words have been shown to deter women from applying 3. Promotion and recruitment are both affected by gendered language.

Despite the evidence, challenging people’s language rarely lands without argument. “Ah,” goes the common riposte, “but ‘man’ just means person”. Man as a suffix or prefix in English tends to come either from the Latin manus, meaning hand, or the Norse mand, meaning person. This might be accurate, but it is also irrelevant. Lucifer literally means ‘bringer of light’ but it rarely features in lists of popular baby names. The same argument is often used against anyone who takes offence at gendered language; “This is the Armed Forces, stop being so sensitive, ‘man’ just means person.” But it is hard to imagine anyone today accusing someone of oversensitivity on the (completely accurate) basis that one particularly offensive racist epithet comes from the Latin word for black. Words have meanings far beyond their derivations. In English, man means man, and its repetition primes our unconscious biases.

For Defence, the old terms are ingrained. The Royal Navy’s human resources section is officially called People, but it still talks in terms of manpower and manning. Naval units still report capability under the headings of Manpower, Equipment, Training and Sustainability, or METS, even though some ships have now quietly moved to reporting PETS (Personnel, etc). Leading Seaman has given way to Leading Hand, but the RAF still wrestles with the conundrum of Airman.

The Impact

The impact of this on women is a quiet but relentless undermining. It creates a masculine environment where women can find themselves feeling marginalised for reasons that are so subtle as to be hard to identify. In turn, this environment creates more opportunities for ‘grey zone’ sexism, incidents that individually may seem trivial but together have an unpleasant impact and studies have repeatedly shown that such incidents can have serious impact on mental health 4 and deteriorating retention rates. The result can be a loss of unit cohesion and reduced operational effectiveness.

So, this is the problem. What is the solution? There are straightforward alternatives for most gendered words. The use of ‘they’ as a singular pronoun is becoming normal – as indeed it was for Shakespeare and Jane Austen, in response to those concerned about mangling the English language. It is easy to substitute personnel for manpower, crewing or staffing for manning, team for guys. There are many senior role models calling for change. WO1 Glenn Haughton, the Senior Enlisted Advisor to the Chiefs of Staff, has called for all Army ranks to be referred to as ‘soldier’ rather than man or woman.

Words are emotive things, and people often resist being told what to use. Leading by example is often better than issuing directives, but encouraging the use of appropriate language within your cohort is a good start. And it is equally important not to overreact. Constructs such as ‘womxn’ lend themselves to ridicule, and ‘Airperson’ just draws attention to the issue in a clumsy way. But avoiding these extremes isn’t an excuse to do nothing. There is plenty that can be done, such as reframing sentences to remove a gendered pronoun, without sacrificing clarity or torturing the language.

More fundamentally, we should examine how we employ words that are associated with masculinity, and look at whether we can balance them. The earlier examples of masculine words in job descriptions are all traits that might be associated with members of the Armed Forces. But Gaucher also lists words perceived as feminine, such as committed, cooperative, dependable, interpersonal, loyal, responsible, and trust. Aren’t these also qualities we would look for in our people? Presenting a balance of masculine and feminine words in recruitment, reporting and promotion may well both improve the lived experience for women and increase the numbers of women joining and staying in the Armed Forces.

It’s Not Just About Causing Offence…

There are still those who don’t see why this matters. The Armed Forces are 90% male, surely using masculine language just reflects that? This misses the point. Increasing the numbers of women applying to join will not only make it easier to meet recruitment targets but also deepens the talent pool, allowing us to select the very brightest and best. Retaining more women stops the expensive waste of trained personnel leaving early. And the benefits of a more diverse workforce are well-documented, from reducing groupthink to improving efficiency 5. Moving towards gender-neutral language isn’t just about avoiding offence, it is about improving the cohesion and effectiveness of the Armed Forces as a whole.

Even if you remain deeply sceptical about everything in this article, ask yourself this: “Without torturing the English language, is there an easily available, readily understood alternative term that isn’t gendered?” If so, why wouldn’t you use it?

Rebecca W

Rebecca W is a serving Royal Navy Warfare Officer with 17 years of experience across Defence. Her current role has allowed her to explore the power of words to bring about change, which inspired her to write this article.

Footnotes

- Malcolm Gladwell, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, Little, Brown & Company (2005).

- Ibid.

- Danielle Gaucher, Justin Friesen and Aaron Kay, “Evidence that gendered wording in job advertisements exists and sustains gender inequality,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 101, no 1, 109-128 (2011).

- Eg B. L Fredrickson & T Roberts, “Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks.” Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173-206. (1997).

- Eg C Von Bergen, B Soper & J Parnell, “Workforce diversity and organisational performance,” Equal Opportunities International, Vol. 24 No. 3/4, pp. 1-16 (2005).