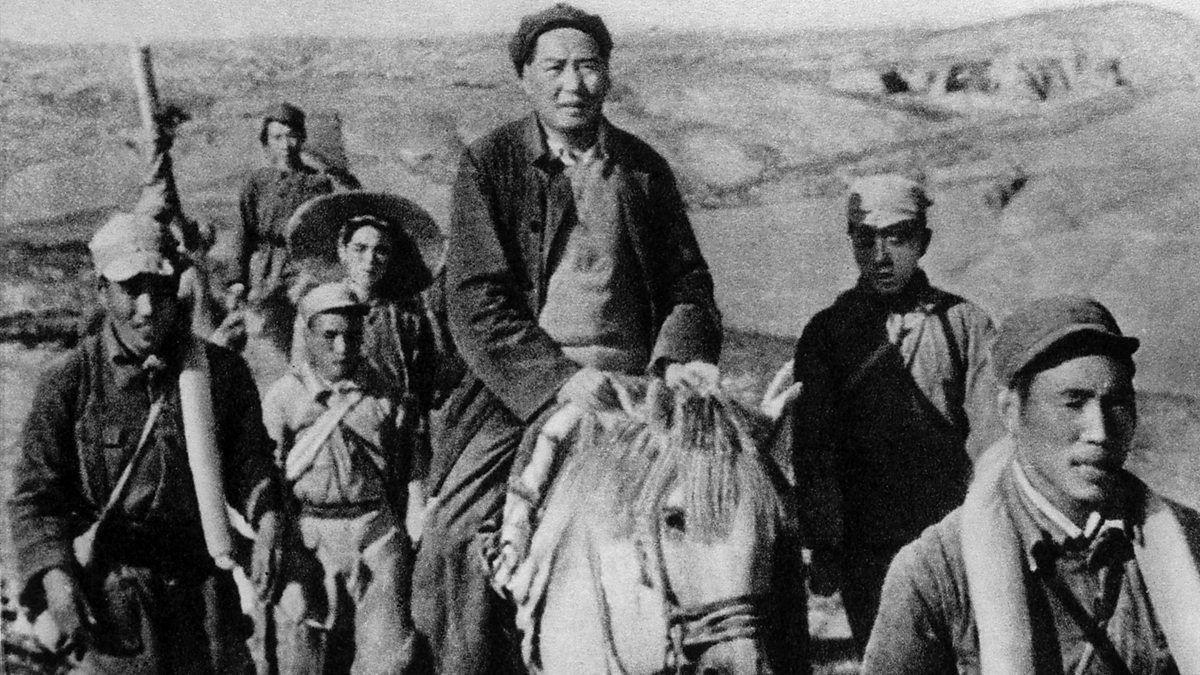

Editor’s Note: This article is the fourth in a four part series which uses military theorists to draw lessons learned from and provide insight on the COVID-19 pandemic. This article covers Mao and brings the series to an end with an overarching conclusion.

Although Mao is a more recent influence on military strategy compared to Sun Tzu and Carl von Clausewitz, he builds on their work to communicate his own ideas, making Mao an effective theorist to end this series. Like Clausewitz, Mao wrote war is inseparable from politics.1 Like Sun Tzu, Mao articulated the importance of being able to transition between offense and defense; defense for when one’s strength does not yet rival the enemy, and attack for when that strength is abundant.2

However, Mao, more than Sun Tzu or Clausewitz, highlighted the enhanced complexity of asymmetric warfare, where the belligerents do not have similar characteristics, and one belligerent, though measurably weaker, leverages tactics like guerilla warfare against the stronger belligerent. Although Clausewitz talks about the friction and uncertainty in war, and even calls attention to the use of asymmetric warfare tactics in the American War of Independence, western European fighting at the time was conducted by military units with a clear chain of command, working within standards and customs understood by all warring powers. Although Sun Tzu’s insights seem less rigid, The Art of War similarly assumes the predominance of organized militaries.

Mao is the master of war on insurgency, a style of warfare in which front lines and divisions between combatants and civilians are malleable. In insurgencies, the offensive and defensive tactics are less structured and the conflicts are often protracted, drawn out and designed to destroy the enemy’s will to fight. The aim is to create such disruption in the stronger, counterinsurgency force’s operating environment that the stronger force relents. In these cases, insurgent forces don’t necessarily have to win the war; they just don’t have to lose. However, in Mao’s case, eroding the “counterinsurgent’s” will to fight provides an opportunity to leverage conventional military tactics to defeat the stronger enemy outright.

COVID-19’s complexity, lack of physical frontlines and invisibility is analogous to an insurgency. It is invisible to the naked eye and co-opts our own species through viral transmission to fight on its behalf. To fight such a complex enemy effectively requires a robust counterinsurgency campaign, understanding more than can be supplied by the conventional military vernacular, at least in the early stages.

This article concludes the series on how the masters of war would evaluate the COVID-19 response. In this article, I introduce the core aspects of Mao’s military philosophy and explain how these tenants apply to understanding the COVID-19 pandemic and the effort to fight it. I then discuss how these ideas align with and advance those of Clausewitz and Sun Tzu, before concluding, again, that the lens of classical military theory might be a guiding force in understanding an increasingly complex environment for warfare of which COVID-19 is just one feature.

Mao’s Model for Insurgency Warfare

Prior to explaining in more detail about how Mao’s military philosophies on insurgency relate to fighting COVID-19, it is important to understand the core tenants of Mao’s insurgency strategy. Mao’s model for insurgency warfare was known as People’s War.3 Overall, People’s War relied on developing a solid base of popular support that could help ideologically, as well as through guerilla warfare tactics, weaken the enemy’s influence over territory, and gradually result in the physical and political control over the country. People’s War relied on both political and military components to achieve the insurgency’s objectives and depended on conducting a protracted war, in which the duration of the conflict frustrates and exhausts the counterinsurgency force enough to facilitate their defeat.

People’s War consisted of three stages. The first stage was known as the strategic defensive.4 The insurgency force would leverage its popular support in a remote area where the enemy lacked influence.5 During this time, there is also a military component. An insurgency could establish control strong enough through irregular warfare and guerilla tactics to make it undesirable for even the stronger enemy to attack.6 This is the stage in which the fighting force, as a result of gaining popular support, is establishing its foundational capabilities to engage the counterinsurgent enemy.7 However, rather than confront the stronger enemy directly, the insurgency force conducts Fabian military tactics. The insurgency avoids mass assaults or engagements in favor of smaller, targeted guerilla attacks that frustrate the enemy, but gain favor among the insurgency’s base of support.8

The second stage of People’s War is known as strategic stalemate.9 This stage is when the insurgency, having acquired key victories and territory, begins to engage and claim military victories and establish forward-deployed military and political bases of operation.10 At this point, the counterinsurgency, represented by the stronger enemy has become exhausted enough that its advance against the insurgency fails to progress and the insurgency begins to grow in strength and legitimacy.11 In some cases, conventional military operations become possible.12

The third stage of People’s War is strategic offense, the transition from a rag-tag insurgency to a conventional fighting force.13 At this point, the insurgency has taken enough territory and gained enough legitimacy from their base that it can directly confront the ruling force more frequently and with relatively equal parity.14 The insurgency is powerful enough to emerge from its remote strongholds to attack, take, and maintain control over small, then large cities, the centers of commercial and political activity, before then assuming control over the entire sovereign territory of that country.15

How People’s War Explains the Spread of COVID-19

The People’s War model for insurgency warfare extends to how the COVID-19 outbreak began and continues to spread in even developed countries worldwide despite the attempts to curtail the virus. Insurgencies spreads via the diffusion of ideas and philosophies. No one will fight unless those ideas are impressed on individuals. However, unlike a human insurgency, the COVID-19 outbreak did not take many years to spread and cause legitimate disruption in some of the world’s most advanced societies.

Based on People’s War, COVID-19 is best characterized as a global insurgency. The first stage of the COVID-19 outbreak began with the first recorded COVID-19 case in an area systemically vulnerable to disease outbreaks.16 Originally, the outbreak was traced to a wet market in Wuhan, the largest city in Central China and capital of Hubei Province. Originally, governments believed COVID-19 jumped from animals at the market onto human beings and, since Wuhan is highly populated, the virus quickly spread around China and other countries.17

However, this assessment is incomplete. A study in The Lancet assessed almost one-third of the original COVID-19 cases had no link to the market, suggesting that before people could contract the virus at the market, the virus had to come from outside. Whatever the origin, food policies, urbanization and population growth made China a ripe target for the first stage of the COVID-19 insurgency.18

Quickly, the COVID-19 entered the strategic stalemate phase where it arguably remains with some countries experiencing increased cases, or, more appropriately, a stalemate in the progress on curtailing the spread of the virus. COVID-19’s invisibility and contagious nature of the threat has elicited inconsistent responses. The more people it reaches, the more strain and exhaustion it places on society. Certainly, the virus is not attaining “popular support” with more humans it infects, but the tactic is analogous to stage two of People’s War.

Some might argue that COVID-19’s disruption of major commercial and political activities indicates the outbreak achieved stage three: the effective takeover of countries and the world. The notion of living with the virus could be comparable to living with the new, insurgency-led regime. However, though COVID-19 remains, increasing in some countries more than others, there remains the opportunity to weaken and destroy the virus before it achieves stage three. Civilization as we know has not entirely crumbled to the point to support the notion of a successful COVID-19 insurgency.

Mao, Clausewitz, and Sun Tzu on the People’s Role in War

A key element in People’s War essential to understanding its application to COVID-19 was the cultivation of support from the people, particularly those who felt disenfranchised.19 In China, this population was located in rural areas. The Kuomintang — the nationalist government that Mao and the People’s Republic of China overthrew in 1949 — lacked influence in the rural areas. A significant reason behind the Kuomintang’s lack of influence in the rural areas — where much of the peasantry lived, was due to class differences. These differences were marked by systemic inequalities and wealth gaps, making people vulnerable to the ideas of Mao and the Chinese Communist Party.

Mao recalled that the Kuomintang government and military also failed to effectively ensure the morale of its people or its forces. 20 Mao, on the other hand, relied on bolstering this morale in order to project himself as a viable alternative to the Kuomintang.21 As a result, Mao had developed a population-based fighting force against it.

COVID-19, like People’s War, essentially relies on a vulnerable and exploitable population-based fighting force to continue spreading the virus. A failure to ensure that a country’s population feels supported and cared for during the virus dictates whether people trust the country’s response. This lack of trust in the response could result in behavior that risks members of the population ‘joining the insurgency’ — (contracting the virus) — like not adhering to social distancing guidelines or not wearing masks.

Though one could argue Mao best operationalized and manualized the role that people have in revolutionary warfare, the role of people in war is not unique to People’s War. People are the third vertex of Clausewitz’s Triangle. The Triangle represents the three necessary components of a war effort, and the people provide the passion, emotion, and legitimacy behind the war effort.22 Without a baseload of support from the rural populations and all subsequent populations in areas his forces occupied, Mao’s insurgency would have failed. Similarly, without the people’s trust, neither the government (political) nor combat elements of the war effort are likely to succeed.

To a broader extent, Sun Tzu argues something similar, though specific to when wars become protracted. Sun Tzu warned states against entering a protracted war, for the longer the war continues, the duller the weapons become and the lower the morale falls among the military forces and the people from the invading state.23 When the morale of the forces fall, so too could the war effort. However, COVID-19 is unique in that the people are also soldiers in the fight against COVID-19. The individual behavior of humans on a massive scale affects how the virus spreads. When the people do not adhere to or trust in the measures in place to combat the virus, it is not only the people’s morale at risk, but the “military’s” as well.

Counterinsurgency and insurgency warfare is often defined as a fight for the favor of the population.24 COVID-19’s contagious nature affords it an advantage in its ability to reach people, as it is literally infectious. The counterinsurgency effort, fighting COVID-19, must take all necessary measures to maintain the integrity and support from the people by protecting and bolstering the institutions designed to support them. The expectation that there will be no vaccine for at least another six months threatens to erode the people’s morale.25 Exacerbating the erosion of morale is the reduced or lackluster effort with which some governments at national, state/provincial, and local levels are countering this insurgent threat.26 If responses do not become more consistent, conscious and contextual, the virus will continue to spread longer than necessary. As an insurgent warfare strategist, Mao would likely see this as an opportunity to continue eroding the will of those in charge, until the frustrated populations demand a change.

Mao and Sun Tzu: Mitigation, Offense, and Defense in People’s War

Sun Tzu’s ideas directly influenced Maoist military strategy. Overall, both Sun Tzu and Mao argued that a force must be able to transition between offense and defense when one’s strength provides such an opportunity.27 Clausewitz, too, said that the defense is often easier than the attack, but that victory relied on transitioning to the offensive at a decisive point.28

As Mao spread his influence to the rural areas through his philosophies about classism and class warfare, he adopted Fabian defensive tactics to lure Chinese forces into the countryside.29 He was then able to leverage his new followers in the countryside to launch guerilla attacks that the Kuomintang forces were unprepared to face. As the violence continued, the fighting became protracted, prolonged, and unyielding, exhausting the Kuomintang and enabling Mao’s People’s War to advance, strengthen and transition to conventional military operations.30

Although COVID-19 is not a sentient organism that can strategize as humans can, the virus’s behavior is similar. COVID-19’s onslaught on global populations prompted response measures involving social distancing and restrictions on freedom of movement. As the lockdowns persisted, populations became complacent, bored, and eager to return to normalcy. These desires resulted in political pressure to relax some restrictions. In some areas, those relaxed restrictions and the resumption of pre-COVID-19 behaviors allowed COVID-19 to re-surge in those areas. When the people’s will to fight weakens and they become complacent, COVID-19 can return in full strength.

Mao also teaches lessons on mitigation, though mitigating an insurgency is not an explicit tenant in his strategy. The lessons learned from Mao about mitigation are best applied to counterinsurgency. Mao’s insurgency model relied on exploiting the social, ideological and geographic vulnerabilities of the ruling class. The class divisions were apparent in the systemic exclusion of some from the economic and political advantages of society, and these divisions were geographically represented with most of the peasant class in the rural areas, away from the centers of power and commerce. To mitigate an insurgency, or to mitigate the worsening of an insurgency, the counterinsurgency must work to shrink and close those gaps. As long as systemic equity remains in a population, the opportunities for unrest and insurgency remain.

Unfortunately, countries like the United States have populations that are systemically more vulnerable to and are contracting the virus at higher rates than others because they have been institutionally obstructed from accessing certain health services more than others.31 Whereas Mao targeted the rural areas for recruitment, COVID-19 is targeting populations that are poor and of color in the United States.32 Because of the failure to address underlying systemic prejudice in certain sectors of society, the vulnerability to COVID-19 has exacerbated those tensions, threatening the vitality of the U.S. response from the inside.

Mao and Clausewitz: Wartime Organization in People’s War

The People’s War model for insurgency warfare contained both political and military components, and the political component was designed to gain legitimate support from the people in the areas claimed through military tactics. As such, like Clausewitz’s Triangle, Mao’s People’s War organization involved the political (government), the military and the people.

The political or government component in an insurgency charts the strategy on which the military bases its actions. However, both the ability to form an insurgency, and the fuel the expansion of one, requires legitimate support and cooperation from the people. The constant and complex interactions between all three components of the Triangle, therefore, are not only a function of symmetric, national military organizations, but those with more fluid structures as well.

In fact, one could argue the success of an insurgency relies more on effective wartime organization than in conventional or symmetric warfare settings. Insurgencies already begin on loose confederations of ideas and forces. The institutional context is more malleable and flexible than long-standing bureaucracies. Although flexibility and adaptability is critical in wartime, some sense of structure and signal of clear expectations can ensure that a war effort is concentrated towards the same objectives, thereby maximizing the chances of victory. If there is an excessive amount of flexibility, than the movement on which the insurgency is based lacks a recognizable identity.

Of course, a “global insurgency” like COVID-19 does not have ideas, nor a political component, but it does have the advantage of having one singular objective akin to a strong tactical insurgency no matter where it strikes. The forces are concentrated on that one objective, and it adapts to stimuli in the environment in order to continue advancing toward that objective. For instance, since the original outbreak was identified, the virus reportedly adapted and changed to survive in other environments.33

The lessons that can be understood about wartime organization in an insurgency still apply to the counterinsurgency. It is not enough to impose restrictions on freedom of movement and other activities to fight COVID-19. The counterinsurgency must also bolster the people, government and combat forces to withstand the effects of those changes. Defensive tactics like lockdowns strain the economy, thereby requiring the government to legislate or institute measures that prevent the economy from collapse. Offensive tactics like allowing and requiring individuals to return to work must also ensure that people have the weapons needed, like personal protective equipment and cleaning supplies, to mitigate contraction and spread of the virus. It is not enough to ensure the integrity of one vertex of the Triangle, for all three are in constant tension with one another. If one receives excessive attention, the others suffer and the war effort is likely to fail.

Mao’s ideas show that an insurgency-like threat like COVID-19 represents a fundamental shift in the types of war the world faces. COVID-19 is a public health crisis, but it is also a security crisis. It has illuminated political, social, and economic shortfalls that anyone could exploit for nefarious purposes and expands the concept of national security to include the security of the individual person. Most importantly, much like the ideologies that spawned Mao’s insurgency, the COVID-19 outbreak shows that the wars nations and communities might face might not be against a physical enemy.

Past Perspectives on the Changing Nature of War

This article series attempted to apply the historical, classical military philosophies from Clausewitz, Sun Tzu, and Mao that to the COVID-19 war effort. Their ideas highlight two important, broader lessons about war. First, even though those ideas come from experiences different from those in the modern day, they can help explain the effectiveness of the tactics used to fight today’s wars. Second, although these ideas are mostly associated with conventional symmetric and asymmetric warfare, their ideas can apply to fighting intangible, amorphous threats.

The means by and the ends to which human civilizations fight war will continue to change, as will the nature of the wars themselves. Regardless, understanding whether a war effort is effective depends on the strength of the strategies developed at the highest levels, the communication of those strategies down to the lowest levels of the war effort, and a reciprocal trust at the lowest levels of those creating the strategies. Only through these means is the war likely to resolve.

Clausewitz, Sun Tzu and Mao all provide ideas on how the effective organization of a war effort, the mitigation and other tactics employed to successfully end a war, and the fluid, intangible nature of the threat can shape the outcome of a war. However, their ideas are only a framework for evaluating and charting an effective war response. Defeating COVID-19 requires broadening our understand of security and war to recognize the gravity of the conflict and inform a cohesive strategy to address it. Then, those responsible must be willing and able to form that cohesive strategy in the context not of the wars of the past, but in the context of the current, amorphous nature of the threat.

Unfortunately, not every country and not every community’s strategy operates with that in mind. This may be because they do not perceive COVID-19 as a threat, but a mere, though severe, inconvenience. They may also be more inclined to preserve short-term political power rather take the necessary steps to ensure the long-term benefit of society. COVID-19 is arguably the most complex and confusing threat seen in many of our lifetimes, but it does not have to stay that way. Learning from those who have fought wars before us might help us figure out how, and to what extent, we do so now.

Jordan Beauregard

Jordan Beauregard is a U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency intelligence officer. He holds a Master of Science in Strategic Intelligence from the U.S. National Intelligence University and studies Strategy, Operations, and Military History at the U.S. Naval War College. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official positions of the U.S. Department of Defense, Defense Intelligence Agency, National Intelligence University, Naval War College, or the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

- Mao Tse-tung, “On Protracted War,” lectures given to Yenan Association for the Study of the War of Resistance Against Japan, May 26-June 3, 1938, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-2/mswv2_09.htm, Accessed May 24, 2020.

- Samuel B. Griffith, “Sun Tzu and Mao Tse-tung,” in The Art of War by Sun Tzu, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963, page 53.

- Emily Feng, “China Declares ‘People’s War’ on COVID-19 — Including Reporting Family and Friends,” National Public Radio, February 13, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/02/13/805760466/china-declares-peoples-war-on-covid-19-including-reporting-family-and-friends, Accessed July 31, 2020.

- Mao, 1938; Major Gordon M. Wells, No More Vietnams: CORDS as a Model for Counterinsurgency Campaign Design, Ft. Leavenworth, KS: United States Army Command and General Staff College, 1991, page 8, https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=722201, Accessed August 1, 2020.

- Mao, 1938

- Mao, 1938; Wells, 8

- Emily Feng, “China Declares ‘People’s War’ on COVID-19 — Including Reporting Family and Friends,” National Public Radio, February 13, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/02/13/805760466/china-declares-peoples-war-on-covid-19-including-reporting-family-and-friends, Accessed July 31, 2020.

- Mao, 1938; Wells, 8

- Mao, 1938; Wells, 8

- Mao, 1938; Wells, 8

- Mao, 1938; Wells, 8

- Mao, 1938; Wells, 8

- Mao, 1938; Wells, 8

- Mao, 1938; Wells, 8

- Mao, 1938; Wells, 8

- Quan Liu, Lili Cao, and Xing-Quan Zhu, “Major Emerging and Re-emerging Zoonoses in China: A Matter of Global Health and Socioeconomic Development for 1.3 Billion,” International Journal of Infectious Diseases 25 (2014), pages 65-72, https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S1201971214014970?token=589A70EFF862CA706EF2F3B1142975C1954473A0AB8ADE1B543373EFC336D742F024400F9AE3FE6F31F914A0CCABE85C, Accessed August 1, 2020.

- Jon Cohen, “Wuhan Seafood Market May Not Be Source of Novel Virus Spreading Globally,” Science, January 26, 2020, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/01/wuhan-seafood-market-may-not-be-source-novel-virus-spreading-globally, Accessed August 1, 2020.

- Quan Liu, Lili Cao, and Xing-Quan Zhu, 2014.

- Mao, 1938

- Griffith, 1963

- Griffith, 1963

- Clausewitz, 89

- Sun Tzu, Chapter 2, Number 2-3

- Michael J. Boyle, “Do Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency Go Together,” International Affairs 86, no. 2 (March 2010), page 336.

- Jonathan Corum, Denise Grady, Sui-Lee Wee, and Carl Zimmer, “Coronavirus Vaccine Tracker,” The New York Times, July 10, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/science/coronavirus-vaccine-tracker.html, Accessed July 11, 2020.

- Gordon, Huberfeld, and Jones, 2020.

- Samuel B. Griffith, “Sun Tzu and Mao Tse-tung,” in The Art of War by Sun Tzu, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963, page 53.

- Clausewitz, 357.

- Mao, 1938

- Mao, 1938

- Neeta Kantamneni, “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Marginalized Populations in the United States: A Research Agenda,” Journal of Vocational Behavior 119 (2020), pages 1-4, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7205696/pdf/main.pdf, Accessed July 11, 2020.

- Kantamneni, 2020.

- Ralph Vartabedian, “The Coronavirus Has Changed Since it Left Wuhan. Is it More Infectious?,” Pittsburgh Post Gazette, June 3, 2020, https://www.post-gazette.com/news/health/2020/07/03/coronavirus-new-mutation-infectious-illness-covid-19/stories/202007030086, Accessed August 1, 2020.