The British Army is trying. The Women’s Royal Army Corp (WRAC) was disbanded and folded into the mainstream Army in 1992. The first female Brigadier followed in 1999 and the opening up of roles outside of support and medical positions culminated in 2018 when the Defence Secretary announced all combat roles were open to women. The National Army Museum timeline shows this progress.

Job done then, right?

Far from it.

While the intention is commendable, the effects are superficial. The lack of senior female officers is an indicator that serious reform is required. If the Army is serious about harnessing all talent, and seeks to be a truly equal employer, then it must alter its nature, instead of treating women like an addendum to be ‘bolted-on’. Women have been far less than integrated, as ‘allowed to join’. The lack of progress in numbers shows the Army is struggling and needs a bold new strategy.

This article considers the different approaches employed in the endeavour for gender balance and draws on examples to evidence their effect. It argues that barriers to change need to be removed and this requires a re-design of the organisational functions (recruitment, training, career structure, talent management, et al) and breaking down of the preconceptions surrounding the role of women in the Army. Many of these observations will resonate more broadly across Defence but this is focused on the Army. Without fundamentally changing the fabric of the organisation, the enduring half-baked approach will fail to achieve anything close to gender parity.

The Imperative for Change

The motives for integrating women can be considered common across any organisation. The first, is that it’s the right thing to do; it’s about equality of opportunity. While this is enough of a reason on its own, it doesn’t speak to the functional imperative.

The second is the drive for a more effective workforce. In the Army, it relates to a better ability to engage with audiences and actors on operations.

The third considers the fight for talent. Women represent 50% of the UK population and around 60% of global university graduates. The Army are competing in a talent-war with the best companies in the UK (and the best paying).

Achieving Gender Balance

Avivah Wittenburg-Cox discusses three approaches that are typically used to achieving gender balance in the military. For the British Army, the first two strategies represent a reluctance to evolve from and discard patriarchal foundations. These approaches give the impression of pursuing gender equality, are generally well meaning and look like success. But in fact, they subvert positive action and are a barrier to meaningful change.

The third approach considers fundamental change to the organisational model, whereby gender parity is baked in from the outset. The Army is a long way from achieving this degree of integration and this serves to highlight the need for a radical new approach.

One: The ‘Honorary Bloke’

The first method is visible, to some degree, across nearly all functions of the Army. It is the laziest approach, in that it doesn’t require a change of culture and can be enacted almost instantaneously.

Training: For the Army, the ‘honorary bloke’ approach is typified by the training function. ‘Soldier first’ is a mantra that snakes its way through the phase one Army training experience. The ability to adopt a firing position, take aim, and fire, is a skill that every Army employee should have. However not every employee is required to close with and kill the enemy. While training must be suitably challenging to weed out those that don’t meet the required standards, the training model needs to ensure it doesn’t alienate a significant proportion of potential applicants (not least women), that may be interested in joining parts of the Army with a lesser focus on direct combat (eg teaching, administration, intelligence, and cyber). The goal should be to test qualities such as leadership, determination, and commitment, without gendering those women that do apply to conform to the masculine affectations that permeate the Army. The RAF training model, which inculcates military values with a very limited approach to combat, may offer the Army one way of changing the system.

Two: A Place for Women

The second strategy will be familiar to many. It represents an approach that is visible across the organisation and is a big part of how the Army looks to integrate women.

“… (it) aims to integrate women by tailoring a limited number of elements to their specific needs. Rather than ignoring gender and making women adapt to the male model, this strategy recognizes and accepts the differences between women and men and addresses them with programs designed for and focused on women (rather than on men). Women’s networks, separate training for women, adapting equipment/ housing/ uniforms all fall into this category”.

Women’s networks: That the Army is a progressive organisation can be evidenced by the much-celebrated women’s networks; they are undoubtedly extremely beneficial to the women that rely on them. On the surface they are a place to feel welcome, to discuss experiences, to get advice on ways to challenge policy, and to ensure the female voice is heard. This seems like a good thing, however the fact that they are necessary is indicative that significant challenges remain.

Women’s networks are needed because the system fails them.

Rather than change the organisation, networks give women their special space so they can better “navigate the male dominated system that continues intact”. The goal should be for these networks to eventually become redundant.

Three: Change the System

The “much rarer strategy is to question the existing model and change it for everyone”. The Shared Parental Leave Policy is an example of how a process can be re-designed to provide a new policy for everyone. These examples are few and far between, but it does show that there is a willingness to engage in these terms.

Senior female leaders. During interrogation by the Defence Committee in July 2020, General Sir Nicholas Carter (the Chief of the Defence Staff), referred to the lack of senior women and the gendered career structure:

To highlight the extent to which change is required, let’s take a deep dive into the lack of senior female officers (defined as 1* and above); it is nothing short of embarrassing.

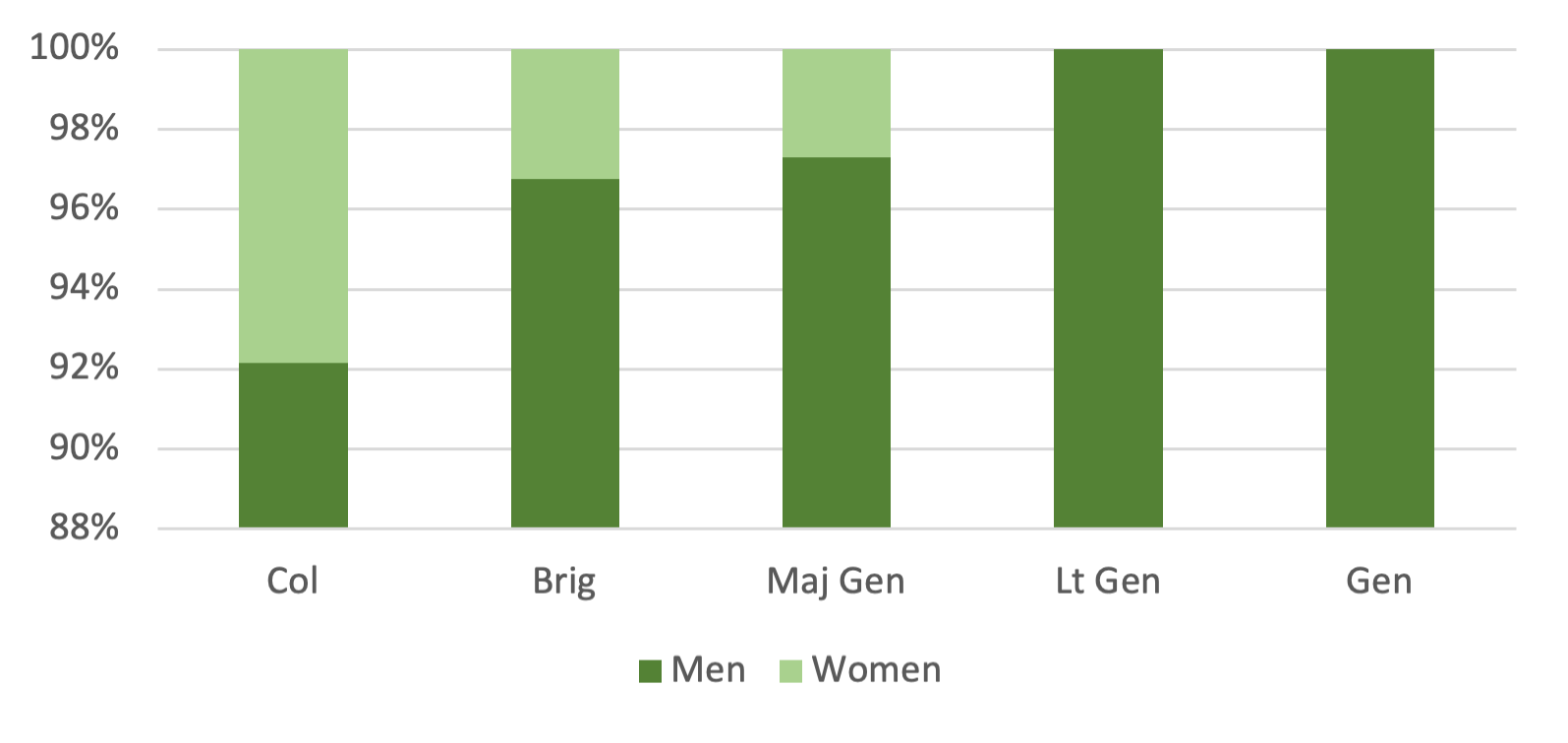

Figure 1 shows how women’s visibility diminishes past the rank of Colonel (OF-5). Official statistics female show representation at OF-5 is 8.4%, broadly in line with the overall Army figure of 11.4%. At Brigadier (OF-6) and Major General (OF-7) however, this is reduced to 3.2% and 2.7% respectively.

In order to understand why this might be the case, we need to take a look at two factors.

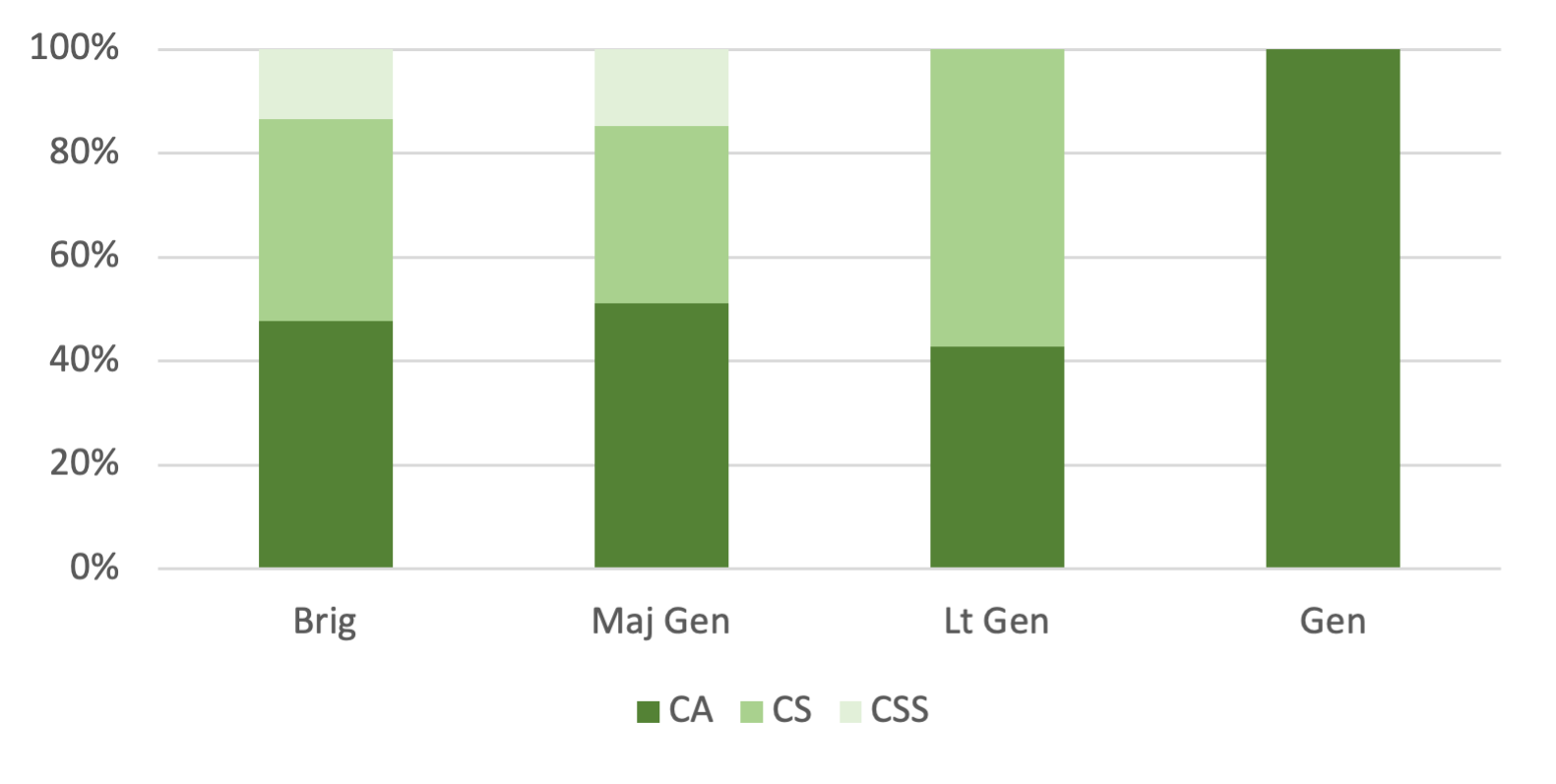

The first is to consider where female officers are employed, followed by an investigation into where general staff officers originated (ie their trade up until OF-5). Figure 2 shows the breakdown by way of combat Aams (CA – eg Infantry and Army Air Corp), Combat Support (CS – eg Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers) and Combat Service Support (CSS – eg Adjutant General’s Corp and Royal Logistic Corp). The stand-out statistic shows that in 2016, 72% of female officers were CSS.

Figure 3 shows where our current crop of senior officers spent their early Army career. The overwhelming majority of general staff officers come from CA and CS. Only 15% of OF-6 and OF-7 come from the CSS world.

It’s here that we come to the crux of the inequality within the Army career structure. We know that 72% of female officers are CSS. We also know that only 15% of OF-6 and OF-7 have a CSS background and yet CSS officers account for almost half of the Army’s total officers.

Positive action is required to address this inequality. One argument may be that now combat roles are open to women the Army will see more women coming through to fill senior positions. CS functions, however, have been open to women for almost a generation and yet women make up only 6.8% of the total CS workforce, compared to 25% for CSS. It is not unreasonable to expect that combat roles will continue to be fulfilled predominantly by men for the foreseeable future. We might therefore look at the selection criteria for senior positions.

Selecting commanders: Does a commander of an armoured infantry brigade need to have been a commanding officer of a combat arm or combat support regiment? Is it only these officers that have the key skills and experience required for modern divisional command? Is tactical experience a prerequisite for operational art and strategic competence? And if so, says who?

Asking these questions begins to challenge the status quo. There isn’t an officer in the British Army today who has commanded a tank regiment in a conventional war in the last decade. It is the understanding of how to apply military capability to best effect that should decide our commanders. The US Army Talent Management Task Force has developed a process for assessing potential battalion commanders. It is also being extended “to determine readiness for command and strategic potential among officers eligible for O-6 level command and general staff positions”.

While in its infancy, and used collaboratively with the extant process, the Battalion Commander Assessment Programme has shown “a 34 percent change in officers chosen for command and key billets”. It is this kind of transformational change that is required to address the paucity of female general staff officers. It is not enough to expect things to change just because we want them to.

What Next?

Changing the system is the panacea. It’s the end game that will allow the British Army to declare itself a truly gender equal organisation and will enable it to achieve the widely accepted 30% representation required to achieve sustainable change.1. All functions that fit within the ‘honorary bloke’ approach need stripping down and rebuilding. This includes initial training, professional military education, uniform (the unisex MTP and female dress equivalents), personal protective equipment (eg body armour), recruitment, career structures, talent management; you name it, it needs changing.

The ‘honorary bloke’ approach, although not a prescribed first stage, is often the first step in accepting women in the workplace. As it is easy to achieve, and requires little by way of policy change, it is where large swathes of the Army remain. Women’s networks, and other such initiatives, are necessary stepping stones to get to an end state that sees a complete overhaul of the organisation that deconstructs the gendered system. It must establish what ‘good’ looks like (the ends), how it plans to get there (ways), and what it needs to achieve it (means). The Defence Diversity and Inclusion team is receiving a significant uplift to enable it to fulfil the requirements of the Army campaign plan.2 These teams must be empowered with a significant budget, combining experience and expertise from across the Army, Civil Service, and the corporate world, to enable it to deliver transformation. They need the time to plan, enact and consolidate change. Defence should accept upfront that this could be a 20-year programme. Women may see increased visibility, but without this level of progress they will still play second fiddle to their male counterparts and the organisation will retain its overtly masculine culture.

This generation is ready for systemic change. The Army’s people are ready to embrace an organisation that is free from gender bias, celebrates gender difference, and champions free choice. The Army needs to take positive action to deconstruct the gendered edifice; choosing to take the hard road and do what is difficult. It’s the battle between the easy choice and the right choice.’

Editors note: this article forms part of our #choosetochallenge series. If you want to write about women’s issues in 2021 check out our call for papers and get in touch if you want to contribute!

Sam Miller

Sam Miller is a serving officer in the British Army. He has completed two tours of Afghanistan, where he worked alongside the Rifles and Royal Marines. He has since worked across several staff jobs and is currently involved in the delivery of change within the Field Army.