In late 2011 General Martin Dempsey laid down a doctrinal challenge by asking ‘what’s after joint?’. The core problem the US military faced, as he saw it, was how to beat anti area access denial systems that would stop them from exploiting their traditional strengths in technology and fire power. The answer, some years later, was multi domain operations (MDO), with the concept principally focused at the operational and strategic level. In the current debate there is a prevailing attitude that land forces can’t conduct MDO at the tactical level. There is also a growing belief that land forces are the consumer of MDO effects and that they have little to contribute to forecast battles. The US Army is actively considering how to achieve MDO at brigade level but the debate in the UK is conceptually stunted.

This think piece challenges this belief and explores how land forces below 2* can conduct MDO. It asks readers to think about capabilities differently and explains why a traditional ground manoeuvre mindset needs to be changed. MDO below the divisional level are not only possible, they are likely to be critical for future success on the battlefield. But the concept has limitations, especially when considering current and future equipment programmes, which must also be understood. A land divisional commander is likely to be frustrated at how their role is challenged in MDO. This article looks at ways a future British division can protect itself from and contribute to a future multi domain operation.

Context and Definition

There is a high level of cynicism around MDO at the tactical level. To many military professionals it represents nothing new and is simply integrating actions to best achieve effects, albeit across more domains than the land component would traditionally manoeuvre in. Part of the problem is a lack of definitions and academic rigour. Squadron Leader Phil Clare argues that the lack of a clear definition is driving a bandwagon effect and, not his words, has become a military ‘fad’. Others have questioned which definition to use. More recent UK concept notes have defined the term as ‘discrete spheres of military activity within which operations are undertaken to achieve objectives in support of the mission.’ At the tactical level, understanding of MDO becomes even more confused. There is an ongoing debate as to whether it is the asset (the physical system which delivers an effect) or the effect it achieves that should define which domain something is in. Arguably the academic definition of MDO matters less than our understanding of what they actually are.

MDO also looks for more options to ‘compete’ in the ‘space’ between peace and war.

The purpose of multi domain operations, or multi domain integration in UK concepts, is to align effects to achieve defined objectives across the spectrum from peace to war increasing the competitiveness of military force. In basic terms, a land force destroys a radar to enable an air strike to enable something else protected by a wrap of space and cyber. MDO also looks for more options to ‘compete’ in the ‘space’ between peace and war.

In that sense, it is nothing new for military planners; capabilities align their strengths against an opponent’s weakness. Especially considering the Ministry of Defence’s recent conceptual model of how to do this, the Integrated Operating Concept. The depth and integration of MDO, however, goes beyond the traditional military understanding by removing barriers between domains and assuming integration as standard. It may be that future land commanders are from the air or maritime domains to enable this higher level of coordination. To some it is a ‘slogan’ rather than a doctrine. Yet, MDO requires staff knowledge and command and control beyond the current scope of most commanders’ understanding to be effective.

The proponents of MDO acknowledge that the concept is immature and that options to achieve it need to be considered. Many will argue that MDO is an operational or strategic concept and that activity at the tactical level can only be ‘joint’. However, simply closing down the debate does nothing to further military knowledge or critically analyse how we may need to consider the future. (Or not, of course). Future MDO requires more data, enhanced command and control, and critically more foresight than current land planners assume.

At The Tactical Level

The debate about MDO at the tactical level is stifled by the strategic roots of the concept. The original purpose of MDO considers how to break complex Russian and Chinese defences using echeloned army groups and whole nation resources. There is a resistance across tactical thinkers to see a need or purpose to change the way we fight. For example, British Army scholar Paul Barnes argues that we should not mistake effect with enablement and that the violence required to win can only happen in physical domains. On the other hand, Brigadier James Cook sees these themes and argues that it is changing the nature (not character) of war away from violence. This overly complicates the discussion, especially when considering how to conduct MDO at the tactical level. The strategic problems at the core of MDO are only larger manifestations of the problems tactical commanders face. US Army Major Jesse Skates uses the example of a divisional obstacle crossing to show this, concluding that MDO must apply at all levels. If the British Army does not start to consider how to do it, then it faces defeat against opponents who already benefit from integrated thinking. Barnes’ argument reinforces the increasingly dominant idea that the land domain is the benefactor of MDO, rather than a key part of it. This is partly driven because land thinkers have yet to codify how a land force might contribute beyond echeloned divisional groups in large scale operations.

MDO at the Tactical Level

None of the options considered below are new or groundbreaking. But considering them in light of the multi domain concept means we need to re-categorise how we consider land power to effectively make the case for the utility of an army.

One of the most important contributions a land force can make is creating strategic ambiguity and deception. A land division can posture and demonstrate on an opponent’s border raising or lowering tension as needed. Coalitions are particularly effective at this as they create greater ambiguity and an opponent must work harder to understand intent. Coalitions can also be used to create dilemmas by aligning force location to political will, inviting an opponent to strike in an attempt to undermine unity. Western military professionals will be uncomfortable with the idea of using proxy forces. However, their use by countries such as Russia has shown the contribution they make in achieving wider objectives.

Smaller forces, such as a UK Division, may struggle to achieve this if we only consider ground manoeuvre. Western forces have a strong track record of electronic warfare. For the British Army the use of Mamba, Asp, and Seller below the divisional level show this. These currently offer only a limited multi domain capability. Future technologies will increase capability and offer an opportunity to make a significant contribution. The idea of the ‘wifi tank’ also merits serious consideration. This integrates across domains yet current thinking, wrongly, does not consider this a form of MDO. This means ground commanders are still thinking in traditional linear terms. To achieve a real multi domain effect, planning must go beyond resourcing ground named areas of interest. It may be that higher formations control these battle winning assets to resource a larger effect, reducing the level of control a tactical commander has.

Another domain which a land force can exploit is space. Current US thinking looks to embed space from the start of an operation and recent publications look to brigade level. For a low level tactical land force the biggest contribution that can be made is resilience, undermining an opponent’s space capability. A modern division has thousands of GPS sensors offering both a vulnerability and an opportunity. The opportunity is to create space deception aligned with wider activity. As Jesse Skates shows, tactical formations will need greater consideration of how to exploit space assets. None of the considerations identified by the US Centre for Army Lessons are beyond the ability of tactical forces to exploit. A resistance to think outside of ground manoeuvre means current British thinking is not examining these opportunities.

There is also a resistance to exploiting joint fires opportunities to strike targets in the maritime domain. This is because tactical formations are focused on the close fight and currently lack the means to do so. Elements of the US Army are actively considering rocket artillery capable of sinking ships. This makes sense given the US Army has over 500 boats to protect, but the British Army is dependent on the Royal Navy and must therefore be prepared to aid the maritime domain. These capabilities cannot remain the sole preserve of the maritime domain. This is especially true when considering the multi domain problem and an opponent targeting rear lines of supply. Not resourcing future forces appropriately restricts a land force to being the consumer of maritime effects and not able to play an active role in a multi domain battle.

The final aspect to consider are the more traditional land tasks of destruction and ground holding. A ground manoeuvre mindset considers these as the principal method of winning a battle. At the strategic level, MDO foresees army groups attacking assets to enable other domains. At the tactical level the concept is the same and land forces can target the means of an opponent to dislocate their effects. A British Army soldier would recognise this as the manoeuvrist approach which is already baked into doctrine. This concept should be updated to better understand what to target, and in which domain it is, to break will and cohesion.

Limitations

For the British Army there is a need for brutal honesty when considering how effective a division may be.

The most telling obstacle to MDO at the tactical level is a lack of knowledge. Staff courses and the UK Defence Academy are not currently configured to train planners with the skills required to conduct MDO successfully. This is partly because of a tradition of operational security. Space and cyber are invariably hidden behind layers of secrecy meaning few planners have a holistic view of capability or know what they could ask for.

This lack of knowledge only serves to silo the debate, undermining efforts to integrate across domains. A look at modern military journals, and even the Wavell Room, finds a majority of articles focused on areas in more traditional comfort zones. Of course, a divisional commander is likely to make the case for more specialist staff to achieve a greater staff expertise. The time required to achieve the experience needed to be specialist is likely to stop sufficient numbers of planners from being generated, meaning the modern Army must increase its own awareness. This is best achieved on staff training courses, without it the Army carries a risk that it cannot plan effectively.

The second limitation is command and control.

The second limitation is command and control. To achieve any form of MDO at the tactical level is likely to require heavy data use, significantly decreasing C2 resilience. A more traditional perspective falls back on coordinating effects and allowing other domain commanders to deliver them. Yet, this closer to ‘joint’. The future of warfare is likely to require more command and control, not less, and land must develop the means to do so. This is likely to diminish the traditional role of a land component commander.

The final limitations are technology and standardisation. Walk into a modern British Army tactical headquarters and you will be faced with map tables and post it notes. A separate map overlay for space and cyber effects is a halfway house solution not exploiting the technology on offer nor allowing dynamic decision making. These linear methods do not enable a commander to easily visualise a multi domain battle, forcing thinking to be focused on ground manoeuvre. Coalitions particularly face interoperability problems which limit the ability to integrate cross domain activity. Yet, the land environment is an oddity when looking at forces in other domains. NATO aircraft, for example, follow standardised baseline standards. Ships also transfer voice and data in a way which is far beyond most multinational land forces. This requires a high level strategy to achieve. For the UK and US, this direction has been given showing the will to resolve this problem. Time will tell if Britain’s Generals follow through on political promises made, but the air and maritime domains offer a model to follow.

Conclusion

The debate about how new MDO or integration is will continue for some time to come. Cynics will argue it is a more complex timeline and supporters will counter that the level of integration required to achieve it is beyond current thinking. In due course military thinkers may well determine that MDO is nothing more than a fad and a new name for joint operations.

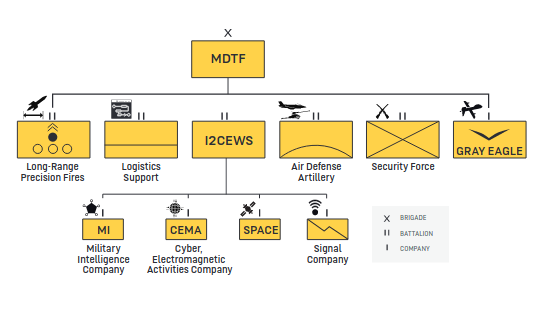

Yet, this debate matters less than the deductions which fall from it. The ability to integrate effects from all domains will be critical in future wars. The increasing need to integrate at the tactical levels means we cannot no longer pretend that campaigns are made up of supporting domains for effect; they must become ‘purple’ and staff must be moved from their single service stove pipes. This is particularly true if the British Army wishes to remain the partner of choice for the US. As such, more thought is needed to consider how a British brigade or division might offer a US multi domain task force credible options. Part of this is re-categorising current capabilities. But this debate should also influence force design; the British Army needs to burst its traditional comfort bubble and think multi domain.

Steve Maguire

Steve Maguire is a British Army Officer serving with The Royal Irish Regiment. He has served at regimental duty, with an armoured infantry brigade, and with the Army Headquarters. He is also the Wavell Room Senior Land Editor.

The views expressed in his writing are his and do not represent the views of the Ministry of Defence.