How adopting a compassionate approach could benefit the organisation, your team and you.

As a Medical Support Officer; I have spent my service career in an inherently caring profession. When Michael West and Suzie Bailey published their compassionate leadership concept in 2019, despite all the professional military eduction(PME) I have done, I immediately thought that it was the leadership model I connected with the most.

I have confidence that the compassionate leadership model can help support us navigate some of the workplace challenges that are further up the agenda than they have been in previous years. Challenges such as: how to thrive in the workplace; how to improve overall well-being and health; as well as how to improve recruitment and retention.

In this article I will discuss what I believe compassionate leadership offers and opens for us in Defence: A new era, a paradigm if you like, that so many Service strategies and initiatives have been striving to instil in us for the last decade or more.

The Myths of Compassionate Leadership

Compassion and some areas of Defence have obvious connections, healthcare and chaplaincy for example. For some areas and roles involved in the front-line execution of warfare; the concept of compassionate leadership could give rise to thoughts of ‘If I am a compassionate leader, people will’:

- Be less committed to delivering on Ops and the quality of output will drop.

- Not be able to have tough management conversations or be able to exercise disciplinary action.

- Opt for the easy, consensus way forward rather than make tough decisions.

- Not be able to challenge the status quo or be a change-maker.

- Lose control over teams and the power within the organisation will be held by whoever is most ruthless.

If that is you then please take comfort in the fact that it is highly unlikely that these factors would manifest themselves if a compassionate approach to leadership is adopted. So then: What is compassionate leadership?

What Compassionate Leadership is

Michael West and Suzie Bailey discuss the myths of compassionate leadership and demonstrate that if you are a compassionate leader the very opposite of what is outlined above is likely to happen. The central tenets of compassionate leadership are attending, understanding, empathising and helping1. Attending is paying attention to those around you and noticing that they are, perhaps, more withdrawn than their usual self. Understanding is taking the time to find out what is causing the distress. Empathising is to respond with care to the other’s distress. Helping is the thoughtful and appropriate action to aid or support the relief of the other’s distress.

At least, that is the theory, but what does it look like in practice?

What it looks like in practice

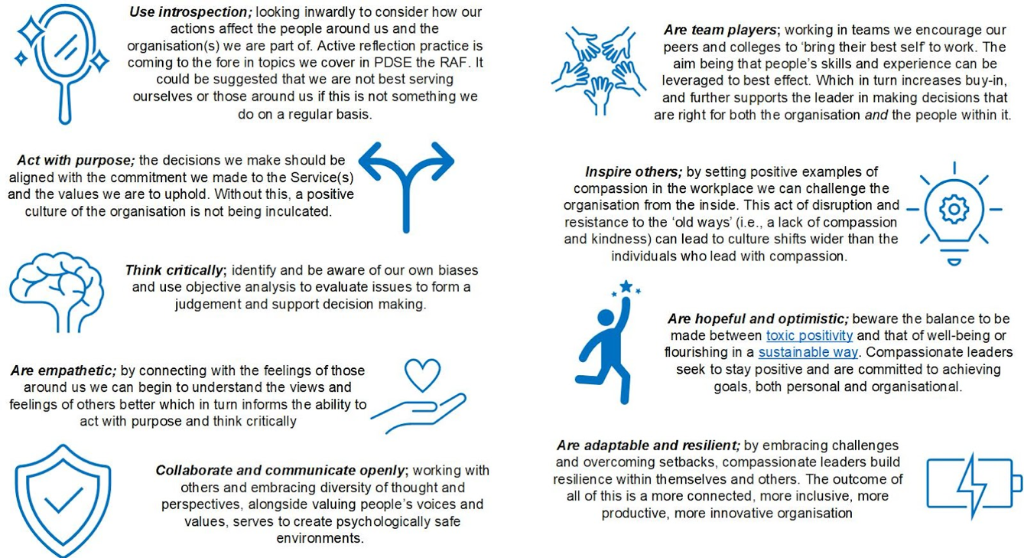

I acknowledge that models often oversimplify the matter at hand, but in this instance, it may help to further illustrate the issue if I offer, through Figure 1, the traits and skills needed to embody compassionate leadership.

Figure 1: Traits and Skills of Compassionate Leaders

Toxic Positivity Theory Sustainable Way Theory

I can, however, sense that some of you are thinking ‘That’s all well and good Jen but it’s a bit woolly isn’t it? It’s all a bit, you know, qualitative’, and you are right. The next section is where I illustrate the case for compassionate leadership with quantitative, statistically significant, longitudinal data findings.

The science behind Compassionate Leadership

In their 2019 book ‘Compassionomics – The Revolutionary Scientific Evidence That Caring Makes a Difference’, Stephen Trzeciak and Anthony Mazzarelli expound a two-year research project into the data behind compassion in healthcare settings to establish if there was science there rather than ‘just’ art. What they and other researchers discovered is that there is science behind the demonstrable benefits for compassion in organisations and their leadership. I will use their main conclusions alongside the compassionate leadership Principles from NHS Wales’ Leadership Portal to model how their results could impact Defence.

Compassion is associated with better psychological outcomes for people, including relief from depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. The main factor at play here? If leaders have compassion for their teams; team members take better care of themselves and could be more likely to ask for help and to follow through on programmes (e.g., referral for Mental Health support). A healthy workforce is one that carries fewer absences, puts less strain on other team members and therefore productivity is maintained or improved.

By developing supportive and effective teams that focus on inter-team working, we can establish the conditions for our people, and therefore workforce, to reflect, learn and innovate. High functioning, innovative teams who feel invested in work more effectively and efficiently. Tie all those elements up across the military and there could be improvements to be had on financial performance in what Treciak and Mazzarelli term ‘bending the cost curve’.

This ‘bending the cost curve’, or, improved financial performance could mean that there is more available to be invested in Defence Estates, Unit Infra or help fund developments in Future Commando Force, Space, Future Soldier all of which are trying to secure finance from what is, at core, the same pot. Taking one aspect of that: If infrastructure, such as accommodation for personnel, was improved on units there is the potential that retention would go up. In a similar vein recruitment could get easier because potential recruits would hear fewer horror stories. Safe, trusting and trusted people will themselves develop engaging systems and good cultures. Which of itself can create environments where collective leadership thrives.

An organisation that is compassionate and people centred, one that fosters better relationships as opposed to more ‘traditional’ leadership models like ‘laissez-faire’ or ‘autocratic’, may be more likely to find themselves a high performing team2. This is due to the fact that behaviour is managed positively, openly, courageously, ethically and at the lowest possible level unlike several more ‘traditional’ leadership types.

Trzeciak and Mazzarelli also found emerging evidence that compassionate workplaces that focus on personal connections are less likely to suffer from the extensive burnout that a global pandemic and relentless operational tempo could induce. Less burn out equals more people in work doing what they do best: bringing their ideas and skills to ensure organisational success. With that comes improved equality, inclusion and diversity because more of the workforce is present more of the time. Maximising equality, inclusion and diversity still requires positive action to consciously remove barriers and boundaries. Bear in mind, also, that compassion is good for the giver as well as the receiver. All the points above include the person giving the compassion too.

Again, at this stage: ‘I remain unconvinced Jen’. You may be conscious of time constraints as a limiting factor and a reason not to take the opportunity to try this leadership style. Would that change if I tell you it takes 40 seconds?

40 seconds is all it takes for a healthcare practitioner to communicate with compassion. Phrases like ‘I know this is a tough experience to go through’, ‘I am here with you’ and ‘we will go through this together’ are all phrases that we can add to our conversations. In tandem you have: Strengthened respect for you; shown the person you are talking to that they are heard; that choices can be made collegiately; and the future can be influenced for the better.

Conclusion

The art of compassion, the qualitative side, can also be measured in quantitative and metric-based ways. There is, therefore, a science to compassion after all. It is a moral and humane approach that lies at the heart of compassionate leadership but there are significant organisational gains that can also be made too. In the face of both quantitative and qualitative evidence for the use of compassionate leadership the questions I pose now are:

Why wouldn’t you give it a go?

What have you got to lose?

Have a wonderful day.

Jennifer Hutton

Squadron Leader Jennifer Hutton is a post command Medical Support Officer in the Royal Air Force. She is currently in a directing staff role at the Royal Air Force Division of the Defence Academy of the United Kingdom delivering professional defence and security education to the Intermediate Officer Development Courses.

Questions, queries and points? Jen can be found on twitter @jenjenhutton.

Footnotes

- Atkins PWB, Parker SK (2012). ‘Understanding individual compassion in organisations: the role of appraisals and psychological flexibility’. Academy of Management Review, vol 37, no 4, pp 524–46.

- Amy Edmonson’s 1999 paper discusses conditions (such as these) necessary to generate high performance outcomes.