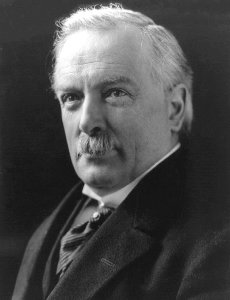

A little over a century ago, on 19th September 1914, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, delivered a stirring call to arms against Germany in the Great War. Honour was cited as the prime reason to fight. Lloyd George, who became Prime Minister in 1916, invoked “our honour as a country,” compared to the “national dishonour” of reneging upon treaty commitments to protect Belgium. He offered a vision of the future in which Britain had scaled “the high peaks we had forgotten, of Honour, Duty, Patriotism, and, clad in glittering white, the great pinnacle of Sacrifice”. A hundred years on, as we approach Remembrance season again, these principles can appear political posturing. This article will explore their significance at the time. And, once realisation of prolonged war had set in, far beyond the hopes of it all being over by Christmas 1914, what motivated men in the trenches to endure and fight on.

Ideology or allegiance to friends

The question of what impacts combat motivation and an army’s morale is as old as warfare itself. Clausewitz cautioned against misjudging the mood of an army, as changeable as the weather, with its intrinsic spirit. That spirit allows an army to resist and to fight. More recently, two main schools of thought have emerged: the first, legitimate demand, suggests that armies fight for ideological reasons. These could be patriotism, religion, hatred or honour, as Lloyd George espoused. The second, the primary group, argues that group loyalty is the key motivator; soldiers fight for their friends. The ideological argument has typically been used to account for the indomitable will of fanatics, from Nazis to the Viet Cong. Extreme ideological motivation is used to explain suicide bombers today. Men fighting for their friends, alternatively, have framed many a Hollywood war production. Look no further than Band of Brothers. Loyalty is a common theme when considering what holds Western armies together when under fire, but ideology is more typically used to explain enemy actions than our own.

Live and let live

A prevalent narrative of World War One is that there was little animosity between soldiers facing each other across no-man’s-land; what emerged instead was a spirit of live and let live. The epitome of this attitude was the 1914 Christmas Truce, captured during the war’s centenary in that Sainsburys advert. To what degree this is posterior myth making is an ongoing debate, but it seems clear that tacit truces were common in the frontline, be it at breakfast time or an opportunity to visit the latrines. The French philosopher Montesquieu argued in his 1748 Spirit of the Laws that humans are not naturally prone to hatred. It is social interdependence, such as competition between nations, which leads to conflict. Even the French in the First World War, an occupied force with more reason to hate than most, shared unofficial ceasefires with the Germans, inevitable perhaps in a trench system that spread from Switzerland to the Somme. The British, it is argued, were even less prone to hatred. Lord Moran, a medic during the Battle of the Somme with the 1st Royal Fusiliers, said: “I cannot recall a single man who lost his temper with the enemy.”1 According to Moran, the British, by design, are not predisposed to such motivation.

Live and let die

Good relations with the enemy were not deemed positive to the war effort amongst World War One commanders. Temporary armistices were strictly banned, and the propaganda machine made great efforts to demonize the other side. In Britain, Germanophobia ran wild during the war, national media mobilizing against “the hated Hun”, supported by posters depicting German atrocities in Belgium and other “murders by the Kaiser” such as the 1915 sinking of the Lusitania. If not yet so sophisticated, Germany made similar efforts to undermine “perfidious Albion,” even raising a popular Hymn of Hate and routinely shouting “Gott Strafe England” (“God Punish England”) across the trenches. It would be naïve to suggest that domestic propaganda had no influence on the battlefield. One German officer noted with satisfaction on arrival at the Western Front that it “brought us into touch with the hated English”.2

As war developed, soldiers had further cause to hate. Death of friends and comrades could prove a strong motivating factor to fight. Second Lieutenant R.L. Mackay wrote in October 1916: “12th Oct. Gas shell attack 5 to 6 a.m. Made me wild. Don’t want to take prisoners after this.”3 Capture of prisoners on both sides presented opportunity for hatred to overcome restraint, and mercy was not always the outcome. It is a little over a decade since the death of Harry Patch, the last British soldier alive that experienced fighting in the trenches of the Western Front. He did not speak of his wartime experiences until he turned 100 years old. He said that at first, he and colleagues aimed their shots to wound, not kill the enemy; he could not kill a man he didn’t know. Weeks later, however, his motivation had changed: “If I had met that German soldier after my three mates had been killed, I’d have no trouble at all in killing him.”

Fighting for national honour

Honour, alongside duty and sacrifice, was a more familiar concept amongst European armies in 1914 than hatred. At the outset of the war, honour, the quality of knowing what is morally right, was cited by all sides as a justification for conflict. On the German side, the Kaiser proclaimed that the nation was forced to draw its sword to “fight for our national honour;” Austria said that it entered the war against Serbia, following the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, “in defence of the honour of my Monarchy”. The language of honour and sacrifice in Lloyd George’s speech in September 1914 echoed the heroism and nobility of spirit of chivalric knights, as well as national heroes such as Nelson who sacrificed themselves for the nation. Stemming from Christianity, the idea of redemption through honourable sacrifice was commonplace in European tradition, repeated in literature throughout the war.

To what extent any of this sentiment mattered in the trenches once the early rhetoric of war was over is open to debate. AJP Taylor argued that Edwardian idealism died on the Somme, yet the language of sacrifice continued to be used throughout the war to motivate men to fight. Field Marshal Haig’s special order of the day in April 1918, as the British line almost broke under the weight of the German Spring Offensive, called upon men to respect the debt to the dead: “We owe this to the determined fighting and self-sacrifice of our troops.” Ideology continued to play a motivational role for at least some men to fight. Soldiers of the 2nd Scottish Rifles in 1915 were described as being possessed of “an unquestioning devotion” to serve their country.4 Yet other efforts to boost idealism in the war fell on deaf ears. General Ludendorff’s attempt at patriotic instruction in July 1917 backfired, lessening German commitment, while Field Marshal Haig’s ‘God and Country’ policy, via speeches and sermons, seems to have carried little weight. Love of country, honour, duty and sacrifice were recognised ideological motivators in the First World War, but soldiers were quick to resist any usage by their commanders out of the heat of battle.

The crack of the whip

Coercion held equal cultural significance in the Great War, especially in militaries raised in the spirit of iron discipline. The European tradition in 1914 was less mission command and more “mechanical obedience based on punishment and fear”.5 Discipline in the British Expeditionary Force included capital punishment at the most extreme end, and a range of measures available at the tactical level including Field Punishment number 1 (known as crucifixion), which permitted tying a soldier to a wheel or post and leaving them to suffer in public view for days on end. There were 60,210 administrations of this punishment from 1914 to demobilisation.6 A significant part of discipline was clearly deterrence – consent through fear in order to keep soldiers in the fight.

However, coercion had it limitations. There were also occasions where discipline broke down. Each European army seemed to pass through a period of low morale, in which discipline failed to stop the outbreak of dissent. Around two-thirds of the French Army mutinied in 1917. This took place not during combat, but rest. British mutinies occurred in 1917 during harsh training at Etaples. Periods of recuperation or preparation were dangerous times for ill-discipline, perhaps due to separation from unit leadership or simply the opportunity to protest. Italian discipline was at its lowest during their huge retreat at Caporetto in 1917; while many factors may have influenced this near catastrophic defeat (tactics, training, communications, leadership, domestic unrest), the severity of Italian discipline had little effect in mitigation. General Cadorna’s policy of random “decimations” – shootings and sackings to instil discipline – was later reversed by his successor, General Diaz, to more positive impact.7 Discipline was not fundamental in motivating soldiers to fight and their consent could be withdrawn depending on circumstances.

Summary

There were a continuum of factors that held importance in the front line in the Great War: loyalty and allegiances, be it to a unit or a social grouping; ideology, such as honour, patriotism, hatred, or sense of sacrifice; leadership, in inspiring devotion; and, perhaps to a lesser extent, discipline in keeping men in place, if not necessarily fighting.

Some of these concepts, notably loyalty, discipline and leadership, remain fundamental in armies today. While duty and honour may carry less resonance, perhaps we should not be so quick to dismiss these ideologies as motivational concepts. For they live on, expressed through commemoration of sacrifice, from the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior to the poppies still worn on Armistice Day. The words of Lloyd George hold significance in 2021, even if the treaties we now honour have widened from the Treaty of London in 1839, promising to defend Belgium, to those such as NATO’s Article 5 that bond us in mutual commitment with our international allies.

Gary Allen

Gary Allen is a British Army Officer in the Allied Rapid Reaction Corps. He has served in operations in the Middle East and Europe and has 20 years of experience in single and joint environments as well as with NATO and the UN.

The views expressed in his writing are his and do not represent the views of the Ministry of Defence.

Footnotes

- Lord Moran, The Anatomy of Courage (London: Constable, 1945), 56.

- Captain Huebner, “A Memoir of Service in the German Army During August 1914,” in Memoirs and Diaries https://www.firstworldwar.com/diaries/huebner_memoir.htm (Accessed 25 July 2021).

- R.L. Mackay, “Somme 1916,” in The Diaries of Robert Lindsay Mackay, https://www.firstworldwar.com/diaries/rlm10.htm (Accessed 25 July 2020).

- John Baynes, Morale: A Study of Men and Courage. The Second Scottish Rifles at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle 1915 (London: Leo Cooper Ltd., 1967), 57.

- David Englander, “Mutinies and Military Morale,” in The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War, ed. Hew Strachan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 192.

- Anthony Fletcher, Life, Death, and Growing Up on the Western Front (Yale: Yale University Press, 2013), 178.

- John Gooch, “Morale and Discipline in the Italian Army, 1915-1918,” in Facing Armageddon: The First World War experienced, ed. Hugh Cecil and Peter H. Liddle (London: Leo Cooper, 1996).