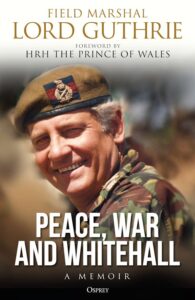

Field Marshal Lord Guthrie had an impressive military career. A Welsh Guards officer and former Chief of Defence, there are numerous blushing compliments in the foreword and cover art. He shaped his regiment, the Army and Defence through the Cold War and the era immediately before the War on Terror.

The book is a memoir; it’s not meant to be academic or overly analytical. Allan Mallinson praises it as offering ‘profound wisdom… written with wry humour and a deceptively light touch’. It’s also a quick read, taking me three sittings over two days and I enjoyed reading it.

However, despite these qualities, I didn’t consider it to be a good book, and I disagree with much of the commentary about it. If anything, it’s one of the more pointless military memoirs that I’ve ever read. Many have recommended it for the insights it offers into military strategy and leadership. Sure, there’s some. But much of the book recounts his time at private school, the behaviour of his assistants, or how he rated senior politicians. One could suggest that people are reading it because of who he is, rather than what he has to say.

The honesty

Guthrie is pretty open about problems he encountered in service. Two of these stand out and resonate with a modern reader: service housing and the will to fight (my words, not his).

Guthrie describes how he stank of paraffin after having to use a heater at Shrivenham (whilst attending Staff College) as the central heating in his first service quarter didn’t work. His wife, Kate, “by now, knew what she had let herself in for”. He is seemingly resigned to this issue, accepting the chronic problems in the system he served for four decades. This theme continues, though as he gets more senior the problems with housing seem to disappear from his thinking and his memoirs switch to the performance of his house team.

Secondly, he argues that the Army’s edge was blunted by its time in Northern Ireland, leading to the loss of reputation when fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan. Guthrie’s operational experience was beyond Northern Ireland, with time in the SAS, but it struck me that he critiques an Army for losing its edge at the exact same time he was responsible for keeping it sharp.

Nonetheless, this honesty is refreshing. It offers an insight into problems and how they were (or weren’t) engaged with by the Army’s leadership over decades. This does have some historical value.

The problems

Guthrie’s memoir is important, perhaps, for what it tells us about the Army he served in. I was disappointed at the numerous mentions of private schools. As the book develops, the relationships he describes all have their basis in wealth and nepotism, rather than the Army selecting the best people for the job. The book’s gushing foreward from the (now) King and the mentions of his encounters with the late Queen Elizabeth II, both point to a life of privilege. Indeed, a cynic might say that those rushing to praise the book are, or wish to be, part of that lifestyle and are unable to objectively compare the book to other more valuable texts. The commentary around it certainly seems to stem from similar social circles.

This could be unfair and perhaps I’m too much of an egalitarian for you to take me seriously. The book is, after all, a memoir and not meant to be a serious text. You could also suggest that Guthrie has picked the moments that meant something to him, to bring out the points he wishes to land.

I finished the book with the impression that the Army is a small world reinforced by relationships over talent. This is almost certainly the opposite message to what Guthrie had in mind when writing. It’s disheartening to feel this when reading the positive spin of leadership and excellence that the text attempts to portray. Much like the Army’s more formal writing on leadership, notably Habit of Excellence, the writing feels hollow and mistakes success with ability, and likability with accountability.

Politics

I was disappointed by Guthrie’s narrative of politics. Guthrie doesn’t hold back on his praise or disdain for politicians. Michael Portilllo (who happened to review the book positively) is outstanding and Gordon Brown (who didn’t) is bad. These extreme opinions miss room for nuance and Guthrie’s text would have more value if evidence and example was used over feelings. For sure, he presents strong views on things like aircraft carriers, but beyond the big ticket discussions the details are lacking, leaving the text feeling lightweight.

Patrick Hennessey commented that the lack of gossip and political point scoring is refreshing, but this description doesn’t really match the text. Guthrie offers strong views on politicians and their ideas about Defence. As Chief of Defence Staff Guthrie confronts Brown when Chancellor, telling him ‘Chancellor, you know f**k all about Defence’. He later critiques others for failing to fund Defence, suggesting it led to the deaths of British soldiers. You may well consider that to be political point scoring. A reader can judge for themselves the credibility of that moment, and others he recounts, and whether Guthrie’s sharp words match his actions as Chief.

Conclusion

Peace, War, and Whitehall is engaging and fun. Guthrie’s respect and admiration for the Army and Defence shines through, and his pride in service and duty are qualities we should all aspire to.

Overall, however, it was just a bit pointless. It didn’t leave me with the view of leadership promised, or the profound wisdom offered, nor did it live up to the positive commentary and reviews the book has received. Compare Guthrie’s memoirs with those of others from his era, Generals Rose and Smith, or The Chiefs, for example, and he falls flat. Their thinking has shaped warfare. Guthrie’s will not.

The commentary on Peace, War, and Whitehall strikes me as a self licking lollipop. An Army reader may use the phrase “the General has spoken, career laughs all round”. There is a strong theme of self satisfaction running through the text and a lack of real self reflection on failure. It’s a shame. The military establishment, as Sir John Chilcot noted when analysing the generation immediately after Guthrie, would benefit from just a bit more challenge and critical thought. Peace, War, and Whitehall is worth reading if you’re after a casual read. But I finished disappointed.

James Burton

Nom de plume. Fanboy of the real James Burton, author of the Pentagon Wars: Reformers Challenge the Old Guard - played by Cary Elwes in HBO's 1998 production The Pentagon Wars.