“We have been inclined to believe that our armed forces are excessively professional and regular. This war [WW2] has shown, as others have done before it, that the British make the best fighters in the world for irregular and independent enterprises….where daring, initiative and ingenuity are required in unusual conditions it can be found from both the professional and unprofessional fighters of the British race.” — Field Marshall Earl Wavell

Tradition and heritage are enduring qualities of many military organisations. The British Army is rich with history and centuries old regiments, but is in danger of being too steeped in its past that it loses relevance in the present. Changes must be made, but without sacrificing grace and warfighting capability. The present zeitgeist is a litany of buzzwords (e.g. “hybrid warfare”, “the grey zone”, “constant competition”, and “sub-threshold”), which swirl throughout contemporary military literature. Strategies and plans are made, but lack execution or meaningful implementation. This is due, in part, to a state of strategic confusion, wherein ill-defined concepts are being deployed without adequate grounding in a coherent theoretical framework.

This article explains why we need a renewed examination of theories. It reinvigorates the British Army’s long tradition of using an indirect approach to thrive in the human domain. War is a political act performed by humans. It is on land, amongst people, that the military must prevail. Defence must posture not only with platforms, but also through investment in highly skilled human operators who have been educated, trained, and equipped to excel in the human domain.

This article does two things. First, it makes the case for why theory is essential to support concept development and strategy. At present, we suffer a cognitive dissonance between concepts and strategy, which is rooted in a lack of foundational theories. A lack of rigorous theory leads to “shallow bumper sticker”1 ideas, which clutters our discourse with unhelpful jargon. Success in the human domain requires concepts and capabilities that are built on a solid foundation of theory fit for purpose, specifically, a theory of a special type of warfare that is waged in complex human environments, using traditional and non-traditional means to achieve strategic advantage. Second, this article explains what types of challenges a theory of this special warfare can begin to solve. ‘Special’ in this case is not ‘better’ or ‘more elite’, but instead, simply different and non-traditional. In the end, this article will show how the British Army can operate globally, with stronger relationships, greater understanding, and extended influence.

Why Theory?

The British Army needs capability and capacity to understand, interpret, and influence human behaviour. It is soldiers who will be on the ground early, working with an indigenous populace, understanding a given situation, and providing critical context to both civilian and military leadership. Soldiers must navigate complex social systems, and operate at a speed that creates vital decision space. Critically, they must do so with an understanding of second and third order effects, ensuring their actions do not create more problems than they solve. Put simply, our warfighters have learned that contemporary tactical actions have direct political consequences2. Our frontline personnel are operating on complex human terrain, where they are often overmatched by competitors with a superior understanding of the local populace, and have far greater leeway to manipulate local dynamics to achieve effects. Without a unified theory in this age of persistent competition, how can we educate, train, and equip soldiers for success?

Our current approach to the human domain lacks depth and rigour. Theory is absent. Methods and tradecraft are underdeveloped, and often improvised. Thinking and theory have been largely outsourced to civilians, forgetting the fact that theory is a core responsibility of military professionals. Theory precedes concepts, doctrine, and strategy3, just like any other profession. Do doctors conduct surgery without understanding theories of medicine, or lawyers practice law without an understanding of its spirit? Perhaps institutions like the Army are ‘running hot’, and consumed by the administrative demands of the day, leaving no time for theoretical exploration and reading. Brilliant battlefield commanders are known to possess coup d’oeil, but this rapid ‘thin slicing’ of situations does not hone the military judgment required for complex problems on a staff. Concept development, strategy formulation, and theoretical exploration require academic study and intellectual engagement. Theory is essential as a description of the elements of the environment, an indication of the workings and interaction of those elements, and a path to determine what winning looks like within defined policy parameters4. Theories also provide a logical structure from which we derive predictions, and those predictions guide strategic choice5.

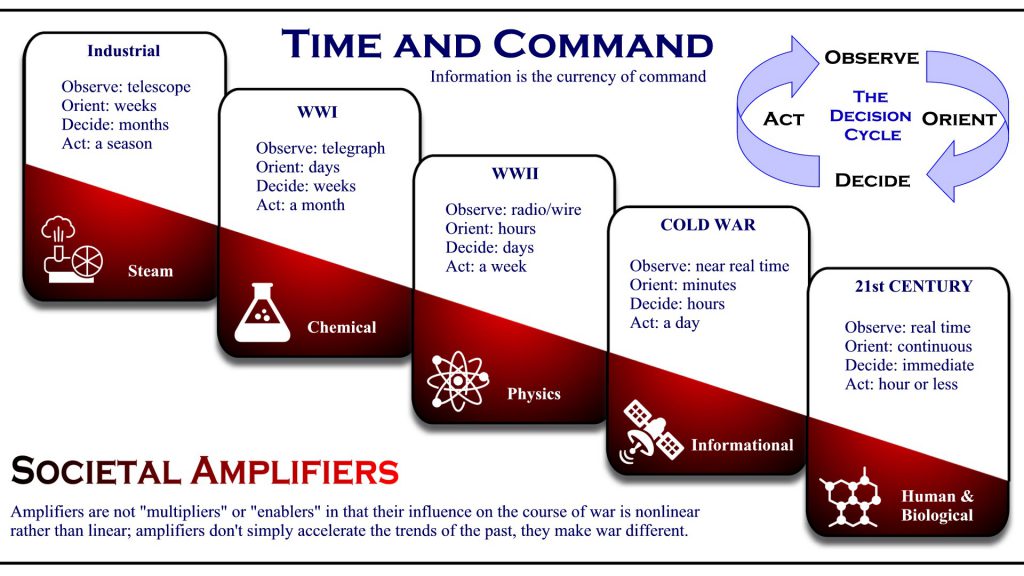

In the context of the human domain, a theory of special warfare is needed. Modern conflict and competition are predominantly a fight for influence. This fight is less decisive than war from previous eras. In addition, there appear to be diminishing returns from the substantial investments made in conventional military weaponry. While many in defence continue to chase technological panaceas, scientists and scholars have declared that the social sciences are the science of the twenty-first century6. Technology is ascendant in our popular culture, yet one general warns that we are entering an epochal shift, where controlling the amplification of competition and conflict will be human and biological, rather than organizational or technological (see figure 1 below)7. Despite the innovations of the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution, the essence of modern warfare and competition remains among the people, and will continue to be driven by the people. As such, special types of soldiers and unique partners need the ability to understand, work with, and influence people.

This indirect way of operating, and attendant capabilities, make this a domain of warfare that can best be described as ‘special’8. We must pause here to echo an important distinction. While we use the word ‘special’, we do not necessarily mean elite or better, but rather different. As Wavell’s opening quote shows, this has long been a core strand of Britain’s strategic DNA. Meanwhile, western militaries continue to apply ad hoc fixes, when entirely new types of career models need to be built to support these modern ways of operating. A new warrior class is needed, to complement our existing lethal force, creating increased battlefield synergy. These new warriors need not be “perfect” soldiers by traditional military standards, so long as they are the “right” soldiers with the right skills for our current challenges. The cyber warfare community has recognized this dynamic, and is adapting its staffing and training model accordingly. Comparable innovations are needed elsewhere across the Army, and a theory on the desired capabilities and effects for special warfare can drive this development. This theory will need to address emergent challenges with strategic compression in the decision cycle, new training and educational modalities, and develop systems for operating amongst and within human networks.

Figure 1 illustration developed by authors, derived from The Age of “Amplifiers” by Alan Beyerchen in Scales on War and “Time and Command” in Envisioning Future Warfare by General Gordon R. Sullivan and Lieutenant General James M. Dubik.

Strategic Compression

John Boyd’s Patterns of Conflict shows how past tactics were unable to keep pace with the maelstrom of complexity in emergent weaponry, arguing that this was a determinant factor that decided outcomes in war. Commanders who clung on to old ways of operating exhausted finite resources on capabilities and platforms that provided limited returns. This dynamic holds true today. The modern strategic compression of both time and depth brings the enemy into our homes, and into our social media feeds. Pervasive access to information presents both opportunities and dilemmas for state institutions. Strategies for data collection and information synthesis are needed to support rapid decision making, and should be incorporated into a new theory.

Scholars and development practitioners advocate an “eclectic combination” of diverse perspectives and methods, revealing hidden connections and dynamic patterns not visible with a single lens9. Collection strategies must leverage thick and big data approaches to unlock greater explanatory power, which leads to detailed causality and a richer understanding of the human narrative. Successful use of these data approaches will require increased cooperation, engagement across the enterprise, and the use of unusual partners. Moreover, many civilian organisations are increasingly locked away behind blast walls, causing a diminished understanding of local dynamics. Teamwork and government fusion is needed to demonstrate new ways of collaborating in the complex human domain.

The Army, operating on land and amongst people, can access dangerous and remote places where civilians are unable to go. It takes specialised and well-trained professionals to provide the insights that enable adaptation and understanding in the face of change. For the British Army, this is no revelation. The British Empire once produced officers like Henry Rawlinson, who decoded an ancient script in Persia10 that unlocked the key to understanding ancient civilizations. There are also famous mavericks like T.E. Lawrence and Freddie Spencer Chapman, whose understanding of local human networks in their environmental contexts enabled them to partner effectively with local forces, bringing hybrid warfare to bear against formidable enemies in the hard pan desert of the Middle East and the dense jungles of Malaya11. However, their skills in decoding human behavior and understanding operational environments were not systematically studied, or written into training manuals. As a result, the British Army has been left only with anecdotal evidence of their successes, as opposed to replicable models and processes that could be scaled across the force.

Human Networks

In the military, we tend to focus on conflict and competition, forgetting about the power of cooperation. Specialised infantry battalions currently train, advise, and assist foreign military forces. A new theory of special warfare can look to expand their operating construct. Specialised units could enable and accompany indigenous forces, building local capacity beyond basic infantry tactics to include institutional development, whilst gathering information about the operational environment. Moreover, such forces could partner more broadly to include the wider security community, both formal and informal, such as police forces, militias, tribes, and civil defence forces within a collaborative network of cooperation and influence12. The Army can operate as a useful platform providing incentives that drive increased cooperation and collaboration across government to include the private sector. They could link to conflict prevention, stabilisation, and prosperity initiatives to these new and non-traditional partners, creating access to new markets for UK equipment and, most importantly, sensing the slightest vibrations of trouble across a web of human networks. A new theory can explore these variables, find incentives for cooperation, and identify training and education requirements for special warfare.

Education and Training: Interdisciplinary Requirement for Special Warfighters

Given the trends noted above, training and education modalities for the modern warfighter must leverage an interdisciplinary approach to the applied social sciences. Interdisciplinary—because not one single discipline is capable of providing comprehensive understanding of the human domain, and applied—because the tradecraft of research, analysis, and implementation must be fit for the reality of the operational context we find ourselves in13. This has been a key challenge for Western forces, as we have struggled to understand and navigate the human domain because of our ethnocentrism. An inability to see the world through non-Western eyes (a weakness that is not shared by adversaries such as Iran, Russia, and China) has limited our ability to exert the types of influence, whether emotional or rational, that can affect human behaviour14. We need to identify the right personnel who have the aptitude to thrive in this space and can adopt an ethnorelative worldview.

Senior leaders have a natural inclination to focus on the macro level dynamics of competition, rather than the local drivers of violence and stability. Yet it is on the ground where local tensions spur bottom-up conflict, and become entangled into a broader narrative that is weaponized to weaken our influence and freedom of action15. Leaders develop the wrong theoretical premise, and form a hypothesis based on a misunderstanding of what we are experimenting with—the human condition. A theory to understand the human condition in warfare, i.e. special warfare in the human domain, needs to expand current education to include causal literacy16 psychology, sociology, and cultural anthropology. These are the foundational disciplines that can explain the variables of human domain in irregular, unconventional, and/or hybrid warfare. It is, necessarily, a bottom-up endeavour that is rooted in local granularity.

Future forces still require the foundational skills of shooting, moving, communicating, and surviving. However, training must expand to the arts of negotiation, conflict mediation, and diverse language skills—rooted within an investigative framework and methodology that will enable tactical level elements to make sense of their operational environment. The ultimate aim of developing these skills and knowledge is to achieve a capability that can effectively act, react, and intervene within human networks’ emotional, cultural, and physical spaces at a rate faster than any adversary17. This necessitates understanding complex internal, indigenous, or traditional cycles of decision-making processes at the local level and, ultimately, creating tactical effects within the population that directly support political and strategic objectives18.

Concluding Thoughts and Way Forward

With a post-Brexit and pandemic-impacted world, the British Army—now more than ever before—requires an agile special warfare capability able to operate in support of strategic objectives, while enhancing the overall effectiveness of all levers of government. The Army can develop small, inexpensive units able to leverage indigenous mass to achieve disproportionately large results. A theory of special warfare, perhaps informed by other work on remote warfare and information warfare19, can build the right capability the UK needs in lieu of what it wants and cannot afford (e.g., more carriers and expensive aircraft)20. This is not a wholesale change of the entire Army and this force may not be like anything that exists today. It can be a force multiplier that magnifies the impact of existing capabilities. A fresh theoretical exploration will exercise our imagination, and determine the right mix and size.

A number of operating concepts in the US and UK find growing interconnectedness, and increased velocity of human interaction around the world. Yet there is currently no system to contend with this complexity, and the wide array of accompanying relationships across multiple human networks. Simply stated, no system exists to track, manage, and map relationships in the human domain outside our normal stare at threat networks. We have to look beyond just the enemy. Many military and government organisations conduct engagements overseas, but they are not meaningfully captured, much less integrated into any knowledge sharing or learning systems. Relationships matter, and can be pivotal in building trust or obtaining a ground-level understanding in inaccessible areas.

These challenges plague militaries and other government agencies at a time when strategic thinking has not kept pace with a radically changing strategic environment. The type of special warfare discussed in this article is a critical element of a wider theoretical debate that must take place within defence. Through such debate, unpacking theory through continued discussion and informed by sufficient rigour and research will help “thresh the grist from the chaff of the conventional theories of war.”21. The military, principally the Army, would be in better position to transform across the operational spectrum:

- At the individual level: We should equip soldiers with the social, psychological, and cultural skills needed to navigate – and influence – complex human environments. This would ensure that our personnel are prepared to assess, engage, and influence on an inter-personal level. Such training and educational opportunities have been implemented by the US Army Special Operations Forces across the globe with wide success.

- At the tactical level: We should institutionalise a robust and scalable framework for investigation of the human domain, fusing best practices from human intelligence, network-centric targeting, civil reconnaissance, and human terrain analysis. At present, these disciplines are stove-piped, and each is poorer as a result. The integration of our assessment and analytical capabilities would ensure consistency and focus in our approach to the human domain, and deliver an integrated, actionable understanding of complex environments.

- At the operational level: We need a significant investment in agile information systems to support the collection of human engagement data by military and civilian elements. A public-private partnership should be formed to develop these shared data repositories, leveraging big and thick data combined with local understanding, to help anticipate crises and coordinate effective responses.

- At the strategic level: Conceptual alignment is absolutely vital to the future of the United Kingdom’s strategic security interests. Facing an array of state and non-state competitors, and with resource-intensive demands from the cyber and space domains as well, the British Army must craft a value proposition that is both affordable and impactful. There needs to be a larger conversation on the centrality of the human domain. Strategic advantage in an environment of persistent competition will emerge from how we engage with and understand the political, economic, and social networks that connect humanity. The Army must help Strategic Command lead this conversation.

Take in sum, this article made the case for a renewed examination of theory, and proposed that a theory of special warfare is needed to contend with the ever-important human domain. The British Army has a key opportunity to field low-cost, human-driven capabilities that assess, engage, and directly affect the strategic landscape. The larger question arises as to whether or not leaders will have the courage to make the case for investment in people over platforms, amidst a culture that privileges traditional symbols of power over those that may not be as visible but yet, are pivotal.

The opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied in this article are the authors’ and do not reflect the views of any organisation or any entity of the U.S. or U.K. government.

Footnotes

- Huba Wass de Czege in emails with author and in Thomas E. Ricks, The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today, (New York: The Penguin Press, 2012), p354-363.

- Emile Simpson, War from the Ground Up: Twenty-First-Century Combat as Politics, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Rachel Reynolds, “Strategy Verbs Theory: A Dysfunctional Relationship,” The Strategy Bridge, (February, 2020): https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2020/2/25/strategy-verbs-theory-a-dysfunctional-relationship

- Joseph A. Gattuso Jr., “Warfare Theory,” Naval War College Review, Vol. 49, No. 4, (Autumn 1996), pp. 112-123.

- Andrew Hill and Stephen Gerras, “Systems of Denial: Strategic Resistance to Military Innovation,” Naval War College Review (2016): Vol. 69 : No. 1 , Article 7, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol69/iss1/7

- Duncan J. Watts, “Twenty-First Century Science,” Nature 445, 489 (2007), https://www.nature.com/articles/445489a

- Robert H. Scales, “Clausewitz and World War IV,” Armed Forces Journal, (2006), http://armedforcesjournal.com/clausewitz-and-world-war-iv/

- Linda Robinson, “Special Operations Forces Organization and Missions,” Council on Foreign Relations, (2013), https://www.cfr.org/content/publications/attachments/Special_Operations_CSR66.pdf

- Rudra Sil and Peter J. Katzenstein. 2010. “Analytic Eclecticism in the Study of World Politics: Reconfiguring Problems and Mechanisms across Research Traditions.” Perspectives on Politics 8 (2). Cambridge University Press: 411–31.

- Yuval N. Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, (London: Vintage, 2011).

- Rob Johnson, Lawrence of Arabia on War: The Campaign in the Desert 1916-18, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2020).

- R.F. Reid-Daly, Pamwe Chete: The Legend of the Selous Scouts, (South Africa: CTP Book Printers, 1999).

- Aleks Nesic and Arnel David, “Operationalizing the Science of the Human Domain in Great Power Competition for Special Operations Forces,” Small Wars Journal, (2019), https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/operationalizing-science-human-domain-great-power-competition-special-operations-forces

- Emile Simpson, War from the Ground Up: Twenty-First-Century Combat as Politics, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Nicholas Krohley, The Death of the Mehdi Army: The Rise, Fall, and Revival of Iraq’s Most Powerful Militia, (London: Hurst & Company, 2015) and Stathis Kalyvas, “The Ontology of ‘Political Violence’: Action and Identity in Civil Wars.” Perspectives on Politics, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592703000355.

- Celestino Perez, Jr., “Strategic Discontent, Political Literacy, and Professional Military Education,” The Strategy Bridge (2016): https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2016/1/7/strategic-discontent-political-literacy-and-professional-military-education

- Christian P.J., Nesic, A. (2017), Foundations of the Human Domain in Unconventional and Irregular Warfare, Valka-Mir Conflict Science Series: US Army SOF Textbook: USAJFKSWC&S, Fort Bragg, NC

- Aleks Nesic and Arnel David, “Operationalizing the Science of the Human Domain in Great Power Competition for Special Operations Forces,” Small Wars Journal, (2019), https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/operationalizing-science-human-domain-great-power-competition-special-operations-forces and Emile Simpson, War from the Ground Up: Twenty-First-Century Combat as Politics, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Martin C. Libicki, “The Convergence of Information Warfare.” Strategic Studies Quarterly 11, no. 1 (2017): 49-65. Accessed April 5, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/26271590.

- Sean McFate, Goliath: Why the West doesn’t win wars. And what we need to do about it, (London: Penguin Random House, 2019).

- JFC Fuller, “The Black Arts,” Occult Review (April 1923).